Millers Falls Company: 1900-1920

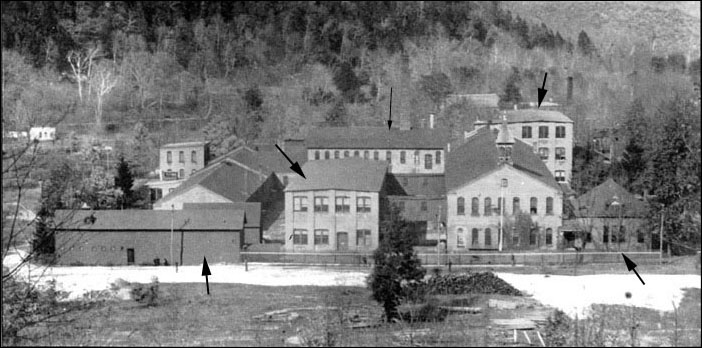

Taken from an undated postal card put out by the E. M. Partridge Publishing Co., the illustration above shows the Millers Falls plant as it appeared about 1905. The image is relatively easy to date since the reverse side is the undivided type conforming to postal regulations in existence between 1901 and 1907. An examination of the photograph shows a good deal of construction had taken place in the previous fifteen years. The black arrows added to the photo indicate structures not present in the 1891 illustration that appeared in Wade, Warner and Company’s Picturesque Franklin County. The smaller arrow in the center part of the image identifies a second-story addition that was added to the boiler building, one of the site’s earliest structures. The small one-story addition, seen at the far right, was built for office space. It housed the general manager and adjoined the office of the plant superintendent. The plant’s main building, the older structure which sports a cupola on its roof, shows no evidence of the disastrous fire which had heavily damaged the back third of the building in about 1900.

Henry L. Pratt, longtime company president and the driving force behind the manufacturer’s success, died of heart failure in December 1900. While Edward Payson Stoughton, the firm’s New York sales representative, is sometimes considered to have followed him in an unbroken company presidency that lasted to 1918. The transition was not so simple, for although Stoughton’s obituary in the October 4, 1936, New York Times has him ascending to the position two years before Pratt’s death and serving as president for twenty years, it overlooks the years in the first decade of the twentieth century when Levi J. Gunn was company president and Stoughton was vice-president. Gunn’s presidency began in 1901 and ended in 1910 when he retired at the age of eighty years. While it is entirely possible that Stoughton viewed Gunn’s presidency as honorific and considered he ran the company from the vice-president’s office in New York, Gunn’s leadership within the firm cannot be ignored.

Levi Gunn assumed the presidency of the company during a period that could be considered the operation's best years. Fifteen percent stockholder dividends had become so common that a report of the annual shareholders' meeting in Greenfield's Gazette and Courier casually noted, "Usual 15 per cent dividend declared."(1) Business was booming, and in 1901, the operation constructed on a new building measuring forty by 220 feet. The first seventy-two feet of the structure were one-story and designed to house the drop forge and blacksmithing units; the second 148 feet were two-stories high and contained the packing and shipping departments. A year later, construction began on yet another building—this one two stories tall and measuring forty by 100 feet. Sales were so good the company added the facilities in the expectation that burgeoning demand would require a twenty-five percent increase in production. The operation was dependent on water power, and with the addition of the new facilities, the increased demand for energy put a strain on its thirty-year-old supply system. In 1903, the business widened and deepened its canal, installed new head gates, and sank its main wheel pit—changes it expected would increase available power by fifty percent.(2)

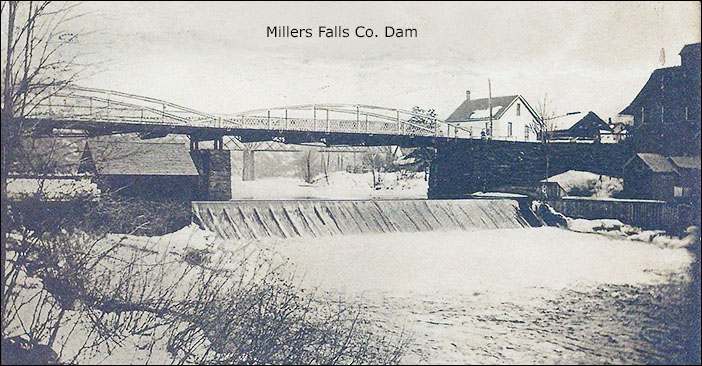

The Millers Falls Company's founders had been careful to secure rights to a substantial section of the Millers River, the source of the water that fed its canal. Hesitant to do anything which might compromise its power supply, the business guarded the resource carefully. Though it had allowed construction of a small dam upstream of its plant to power the local electric trolley, the company steadfastly refused to sell any part of its water privilege to a larger concern. The situation changed in 1902 when a group of investors from Holyoke wanted to locate a paper company upstream of the trolley dam. It dawned on Millers Falls executives that the sale of a water privilege would not only be profitable but that another upstream dam might alleviate chronic problems caused by the annual icing of the river. The new concern, organized as the Millers Falls Paper Company, built a thirty-foot-tall dam across the Millers River, creating a reservoir some three-quarters of a mile long. The new dam provided the papermaking operation with 1,200 horsepower of energy, an amount exceeding the capability of the Millers Falls Company's dam by some 300 percent. The paper plant was a large employer, and the tiny community of Millers Falls soon found itself in the midst of a housing shortage when building projects for the Millers Falls Company and the paper company created a shortage of carpenters. Nonetheless, eighteen new houses were started in the village in 1903. Eight of them were built by the Millers Falls Company for its employees.(3)

Due to its reliance on waterpower, the company emerged unscathed from the Anthracite Coal Strike that nearly paralyzed the country during the winter of 1902 and 1903. The miners' strike began in Pennsylvania during the summer of 1902 and lasted over 160 days. As winter approached, panic set in, and the price of coal skyrocketed. As a result, those seeking an affordable source of energy turned to firewood, a move that, in turn, drove prices for the substitute fuel to seven or eight dollars per cord. Though it is hard for a twenty-first century woodworker to imagine, prices reached the point that the odds and ends of the cocobolo lumber stored on the Millers Falls Company's premises became more valuable for firewood than for hand tool components. The operation was paying thirty dollars per ton for its best cocobolo logs, valued its larger pieces of lumber at twenty dollars a ton and considered smaller pieces had little value. The company began selling cocobolo scrap at six dollars a ton, delivered. Soon the Franklin County Bank was burning cocobolo in the fireplace of its board room, and Millers Falls Company directors Levi Gunn and George E. Rogers burned cocobolo wood to heat their homes. The coal strike was settled by early winter, but fuel supplies remained tight throughout the season.(4)

The tinted reproduction of the plant shown below is taken from a divided-back postcard of the type approved for usage in the United States in 1907. Although published by the Springfield News Company of Springfield, Massachusetts, the card was printed in Germany, a leading postcard manufacturer due to early success in mass producing color lithographs. Representing the plant as it appeared sometime between ca. 1905 and 1910, it depicts two buildings not included in the illustration at the top of the page. Despite the new buildings and growth, conditions inside the plant remained crowded and dreary, as can be seen in the image taken from a 1943 employees' magazine and identified as the "polishing room one year after new building was constructed." Though not necessarily the most cheerful places to work, the new buildings were far less prone to the devastating fires that cursed the older structures. The image of a fire at the most iconic of the plant's early buildings is courtesy of the Museum of Our Industrial Heritage in Greenfield and was once reproduced in the December 1943 issue of the Millers Falls employees' magazine where it was identified as "the last fire at the Millers Falls plant, which was about 1900."

The Millers Falls Company gained complete control of the Langdon Mitre Box Company in 1906.(5) The involvement of the Rogers family in Langdon had been extensive. C. C. Rogers had served as company president; George E. Rogers, while secretary of Millers Falls, had served as treasurer; David Rogers had patented the firm’s miter planer. The transaction was likely a simple affair involving an exchange of shares between various members of the Rogers family and Millers Falls. Although Langdon relied on the Millers Falls Company for the bulk of its sales, it had been putting out a small price list under its own name for some time. The parent company continued the tradition for at least a year after the buyout. A 1907 price list touts the New Langdon Acme Miter Box, the deluxe model that would anchor the line for over a half-century. The list also included, on the other end of the spectrum, the company’s Star Miter Box, an economy model that could be used with either a panel or a back saw.

When Levi Gunn retired, the company that he led had enjoyed a string of earnings rivaling any in its history. The operation employed some 400 workers and had almost doubled its product line in the years since 1900. During his tenure, the business built four major structures (the most recent in the previous year), reconstructed its dam, and made substantial improvements to its canal and mill race. It had just laid the foundation for a new sixty by 100 foot building, and plans were in the works for improving the water power available to the Lower Shop, an area that included structures built in the early 1870s by Charles H. Amidon and his brother Solomon after Charles had resigned as superintendent of the Millers Falls Company. The plans for the Lower Shop called for the installation of four water wheels to replace the existing single wheel, a move expected to would increase the energy available to that facility to 225 horsepower. On his retirement, Gunn sold his interest in the company to George E. Rogers, the secretary of the Millers Falls board. While Edward P. Stoughton was responsible for the success of the sales operation during the first decade of the twentieth century, Levi Gunn and his colleagues in Greenfield were responsible for the growth and efficiency of the manufacturing side of the business. Viewed in this light, Stoughton's claim to have been company president during Gunn's tenure was not only untrue and self-aggrandizing but indicative of a failure to recognize the importance of the manufacturing side of the operation.(6)

Edward Stoughton's presidency

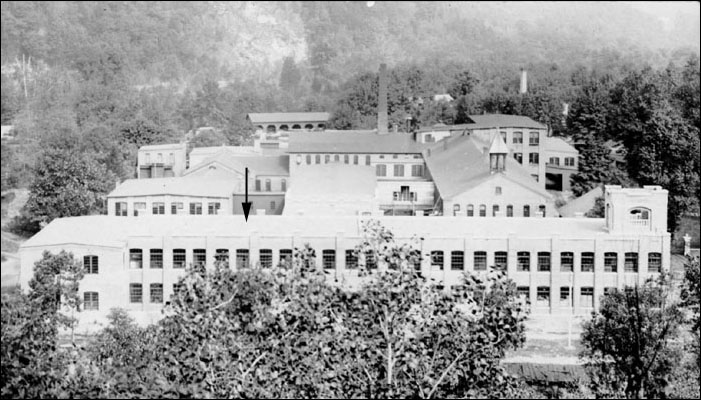

Under Edward P. Stoughton, the Millers Falls Company’s twenty-year cycle of plant expansion came to a close. By 1912, the company had completed what would be one of the last of the major construction projects at its site in Millers Falls.(7) The project, a building designed to accommodate finished goods storage, the shipping department, and areas for boxing and crating, is marked with an arrow in the photo below.

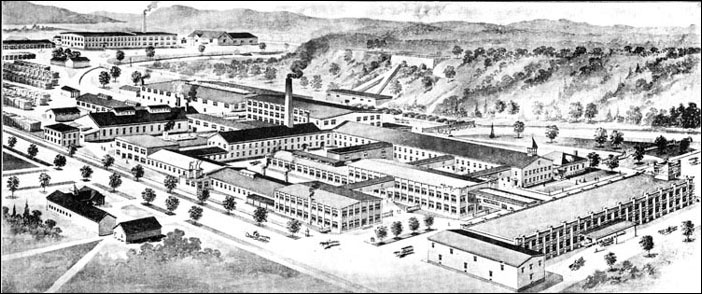

A person familiar with this view of the plant might have found it difficult to reconcile the reality of the photograph with the fantasy that gracing the front pages of the company’s 1912 catalog. In all fairness, the wooded and hilly terrain surrounding the plant made it difficult to get a flattering photograph, and the new building, a formidable visual barrier, compounded the problem. Still, company management must have been delighted with the way the artist turned a scattershot collection of mismatched buildings into the well-organized, spacious marvel of modern manufacturing pictured here.

According to a promotional bit in the September 1912 issue of the magazine Western New England, Stoughton's new building added 50,000 square feet of floor space to the plant, business was booming, and the number of company employees had grown to 500. It also reported, “... the single item of fancy cocobolo wood, imported to be turned into the handles used upon the tools, amounts yearly to several hundred tons.” A photo of the new building’s front entrance and a view of the company’s Automatics Room appear in a two-page advertisement in the same issue.(8)

On May 7, 1912, the United States Patent Office registered the Millers Falls Company's star trademark. In use since 1882 or 1883, the five-pointed star had been used to promote hack saw blades and drill chucks for decades. It began appearing on catalog covers in the early 1900s, and in 1910, covers depicting the star inside a circular band containing the words “Millers Falls Company - Toolmakers” were introduced. In 1914, the trademark was altered yet again, with the star reduced in size and positioned beneath a larger inverted isosceles trapezoid featuring the words “Millers Falls Tools.” This later version of the trademark was registered the following year.(9)

Stoughton’s background in sales may have been responsible for the unprecedented expansion in the number of products sold by the company in the decade between 1910 and 1920. The buildup is interesting in that it was not so much an increase in the types of tools available (a list that ran from angular bit stocks to wrenches) as it was an increase in the number of models produced. An extreme case in point is the company’s bit brace, a tool available in more variations than any other sold by the company. The company boasted it offered the most complete line in the marketplace—254 different braces. Many of the braces varied only slightly from one another and differences could be as small as the presence or absence of finish on the metallic or wooden parts. The number of variants on what is, after all, a simple tool was staggering, and not all of the available braces were added to the catalog. The proliferation of nearly similar tools seems an odd way in which to increase demand, and by the end of the decade, the strategy had fallen from favor. Considering that in addition to its braces, the firm marketed seventy-five different hand and breast drills; push drills; bench drills; boring machines, and auger handles, the Millers Falls Company may well have been the era’s leading manufacturer of boring and drilling tools.(10)

War and revolution

From the time that Edward Stoughton first joined the company as sales representative, Millers Falls had been remarkably successful in selling its tools overseas. The success of Stoughton’s marketing efforts had firmly established the brand in the European and Australian markets; sales to Asia and Latin America were commonplace. In 1914, thirty-six percent of all Millers Falls sales were made to international buyers. With the onset of the First World War, this blessing became a curse. Orders from England, France, Germany, and Russia almost disappeared; economic blockades and attacks on merchant vessels turned shipping into a nightmare. The effect on the Millers Falls Company was profound, and for a time, no dividends were paid to its shareholders. Halfway through the war, the company found a way to circumvent the embargoes, and the situation improved. International sales would represent nearly a third of the firm’s total through the mid-1960s.(11)

Perhaps the unluckiest Millers Falls salesman to be caught up in the era’s political intrigues was E.R. Wilner. Wilner, employed as the firm’s representative to Russia, was in the country at the time of the Bolshevik Revolution. Uninterested in politics, he assumed he would be able to continue selling tools under the new regime as he had under the old. The Bolsheviks, however, angered by the failure of the United States to recognize the new government’s legitimacy, refused to allow Wilner to leave the country and forced him to work for 4,800 rubles per month and a half-pound of rye bread per day. Wilner endured for two years before slipping away in October 1920, and walking eight miles to the border with Finland. There, he was robbed by Finnish guards and sent back to Soviet Russia. Picked up by Russian soldiers under orders to shoot him, Wilner was spared as their commander was away and was marched off to another post where his fate was to be decided. While in transit, he bribed his escorts with money that the Finns had missed and was allowed to return to the border. This time, he managed to get by the Finnish patrols and walk fifteen miles to a railway station. On his return home, a grateful Wilner would refer to the United States, without the slightest trace of irony, as “God’s country.”(12)

The Ford Auger Bit Company

In 1916, the Millers Falls Company took advantage of an opportunity to “purchase outright the stock, machinery, good will and any other assets” of the Ford Auger Bit Company of Holyoke, Massachusetts.(13) Although Millers Falls had been selling augers for decades, the purchase marked its first foray into the actual manufacture of the product. Ford Auger Bit had established a solid reputation based on its manufacture of Ellsworth Ford’s 1891 design for an improved, single-twist auger bit. The firm’s single twist, single lip models cut aggressively, provided good chip clearance, and were favored by many workers for use in basic carpentry. Although single lip bits do not produce the clean, well-defined hole of the double lip varieties, they were marketed as being faster cutting, operating with less friction, and especially useful in end grain and green, wet or knotty wood. Since Ford Auger Bit was also making single-twist, double-lip and solid-center bits at the time of its purchase, the Millers Falls Company had no trouble including a full array of augers in its 1917 catalog. Of special interest is the “Hummer bit,” a single-lip bit designed for fast work in softwoods. The Hummer was capable of boring through inch-thick pine stock in six rotations—twice as fast as a typical single-lip Ford bit and three times as fast as a cabinetmaker’s double-lip model.

In addition to offering four variations on standard-sized carpenter’s bits, the company sold machine bits, car bits, and ship augers. Custom orders were also taken. Certainly the most interesting of these was the bit designed to drill through the timbers used in constructing the locks of the Panama Canal. At the time, the Panamanian auger—a monster boring device—was considered to be the longest auger bit in the world. The company continued to manufacture auger bits at its Millers Falls plant until 1946 when it sold the equipment to the Snell Manufacturing Company.(14)

Real estate and retirement

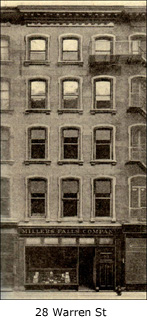

In November 1919, after twenty years of renting, the Millers Falls Company purchased the building housing its New York office. The structure consisted of five floors and two basements and was located at 28 Warren Street, in the heart of the wholesale hardware district. An extensive renovation program was undertaken shortly after purchase, and the company would soon proudly report that it occupied the entire ground floor and basements and that the upper stories were rented to “high class firms.” The front half of the first floor of the Warren Street building served as a showroom for a complete display of Millers Falls tools while the rear portion was reserved for the firm’s export offices. The company’s space needs would have been larger had the domestic sales office not been moved to Millers Falls earlier in the decade. The Warren Street address would serve as Millers Falls’ New York presence for another four decades.

In 1920, Edward P. Stoughton stepped down as president of the Millers Falls Company to become chairman of the board. He had been with the concern since the opening of the New York office some fifty-two years earlier and was the last of the first-generation executives. Charles H. Amidon left the company to establish his own business in 1870; Henry L. Pratt died in 1900; Levi J. Gunn retired in 1910 and passed away in 1916; George E. Rogers died in 1915. A New Yorker to the core, Edward Stoughton’s affiliation with the company ensured he had the means to maintain a residence with a prestigious Fifth Avenue address and to continue his European travels in later life. He died October 3, 1938, aboard the Queen Mary, on a return trip from London, as the luxury ocean liner was approaching the dock. A week earlier, he and his wife had celebrated his ninety-second birthday.(15)

Illustration credits

- Postcard images are credited in text.

- Millers Falls Company dam: [postcard]. Williamsville, Massachusetts: Willliam R. Hale, ca. 1910.

- Polishing room: Dyno-mite, December 1943.

- Fire: Museum of Our Industrial Heritage, Greenfield, Massachusetts. This photo of a photograph is copyright of the author.

- Photo of Millers Falls factory: Undated photo in author’s possession.

- Drawing of factory: Catalogue No. 32 of Millers Falls Company. New York: Millers Falls Company, [no date, but 1912].

- Ford Auger Bit Co: Cover of undated catalog in author’s possession.

- Linked images of new front entrance and automatic room: “Millers Falls Co.” Western New England, September 1912.

- Linked images of Ford Auger bits: Catalog No. L. Millers Falls, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1917.

- Linked image of world’s longest auger bit: Courtesy of Greenfield Recorder.

References

- "Usual 15 Per Cent Dividend Declared." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) January 31, 1903, p. 1.

- "To Make Big Addition." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) May 25, 1901, p. 1; "A Boom in Millers Falls." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) November 23, 1901, p. 2; "Millers Falls Company Enlarges Again." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) November 22, 1902, p. 6; "To Improve Their Power." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) October 17, 1903, p. 6.

- "Franklin County." Boston Sunday Globe (Boston, Mass.) June 1, 1902, p. 2; "The Millers Falls Paper Company." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) December 6, 1902. p. 1: "Millers Falls Builds 18 New Houses." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) November 21, 1903, p. 2.

- "Franklin County: Local Stories of Wood and Coal." Boston Courier (Boston, Mass.) October 5, 1902, p. 2; "Total Coal Receipts Little More Than a Week's Supply." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) January 3, 1903, p. 6.

- “The Millers Falls Co.” Hardware Dealers Magazine, v. 43, no. 253, January 1915, p. 111.

- "The Millers Falls Company Changes its Officers." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) January 29, 1910. p. 2.

- Not including a boiler building added in the late 1940s.

- “Millers Falls Co.” Western New England, September 1912, p. 252. The illustrations are on p. xxvi-xxvii.

- The United States Patent Office registration number for the star trademark, No. 86,431; for the trapezoid and star, No. 110,863.

- Statistics on number of bit braces and drills: “The Millers Falls Co.” Hardware Dealers Magazine, January 1915, v. 43, no. 253, p. 113.

- Paul Jenkins. The Conservative Rebel: a Social History of Greenfield, Massachusetts. Greenfield, Mass.: Town of Greenfield, 1982. p. 189.

- “Salesman Finds Russia Unfriendly to Visitors.” A Century of Experience: Millers Falls Company. Greenfield, Mass.: Greenfield Record, Gazette and Courier, August 13, 1968. unpaged.

- Catalog No. L. Millers Falls, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1917. p. 35.

- On the largest auger bit: “Panamanian Auger.” A Century of Experience: Millers Falls Company. Greenfield, Mass.: Greenfield Record, Gazette and Courier, August 13, 1968, unpaged. The end of auger bit production: “Millers Falls is Name Famous in World of Industry.” Montague 200th Anniversary Edition: Greenfield Recorder-Gazette. (Greenfield, Mass.) June 4, 1954. p. D-13.

- Stoughton’s obituary: New York Times (New York) October 4, 1939, p. 25.