Millers Falls Company: 1948-1962

Tool design

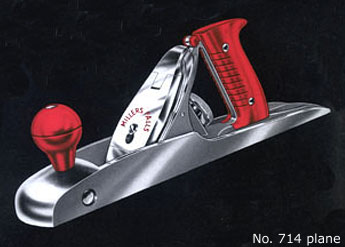

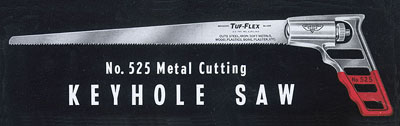

The year 1948 marked the introduction of the most visually sophisticated tools ever offered by the company. By the middle decades of the twentieth century, the idea that mass-produced items should be engineered with an eye to such human values as taste, logic, and beauty had taken hold in board rooms across the country. The Millers Falls Company, too, became interested in the new design paradigm and began working with outside consultants to develop some of its new tools. A series of products, designed to integrate functionality, sound design, and visual appeal was brought to the marketplace. Included in the rollout were the No. 100 push drill, the No. 104 and 308 hand drills, the No. 300 hacksaw frame, several re-designed Dyno-Mite electric tools, and the No. 709 and 714 bench planes. While most of the items were fitted with handles and knobs made of an opaque red plastic known as tenite, some, such as the No. 525 rotating blade keyhole saw, featured die cast components.

The new products were a radical departure from anything that the Millers Falls Company had attempted in the past. A pair of independent industrial designers were brought on board to develop the tools. The No. 104 and 308 hand drills were the work of Francesco Collura, an established designer who used the company’s No. 5 drill as the starting point for his creation. He was responsible for the lever-action, highly styled No. 300 hacksaw frame as well. The No. 100 push drill was the work of L. Garth Huxtable, a New York designer who had just opened his own office. Francesco Collura’s work for the company ended at about the time of Huxtable’s arrival, and Garth Huxtable soon became the Millers Falls Company’s primary outside designer. The work of the two free-lancers proved an inspiration for Robert W. Huxtable, Garth Huxtable’s brother and a draftsman with the Millers Falls Company. In 1950, Robert Huxtable was awarded United States Design Patent no. 159339 for the firm’s No. 709 and 714 bench planes. The planes were a re-thinking of an earlier Samuel Oxnard design for the Sargent Tool Company. The No. 525 keyhole saw, a Huxtable brothers product, featured a rotatable blade and was exceptionally well done—combining a clean appearance, improved functionality, and easy handling in a useful and inexpensive tool.(1)

At the time that the new designs were being developed, the company also began to use red tenite for some of its more traditional tools. A ratchet brace of intermediate quality, the No. 1950, was brought to market with opaque red tenite handles. The 8504 screwdriver set introduced transparent red tenite to the line. The company also began replacing permaloid components with transparent tenite when it changed the handle of the No. 84 hacksaw frame to the new plastic. While tools such as these took advantage of the new plastic that had become available, they remained products of an earlier paradigm.

The company continued experimenting with non-traditional designs throughout the 1950s. Certainly, the most visually outstanding tool of this later period was Huxtable’s award-winning Plane-’R-File. The Plane-’R-File is an example of the replaceable blade rasps that became popular in an era when building materials and construction techniques had changed to the point that a typical homeowner seldom reached for a hand plane. Manufactured with a reversible handle that could be positioned for either planing or filing, the No. 1220 functioned best when used as what it actually was—a rasp. Moderately priced and capable of holding a variety of blades, the Plane-’R-File was well suited to any number of odd jobs around the house.

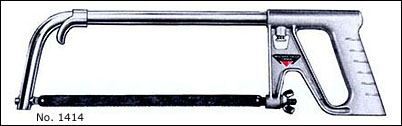

Other noteworthy Garth Huxtable designs from this later period are the No. 1414 hacksaw frame and the No. 895 keyhole saw. The handles of these tools were manufactured of gray-enameled die cast rather than tenite, but the general aesthetic was the same. The crisply-designed tools manufactured by Millers Falls Company during this era have collectively become known as Buck Rogers tools, an appellation derived from the similarity of the handles on the bench planes to those commonly seen on toy space guns. As the Millers Falls Company was also manufacturing products for the Sears Company during this time, it developed several non-traditional models for the retailing giant’s Craftsman and Dunlap lines. L. Garth Huxtable did much of the design work.

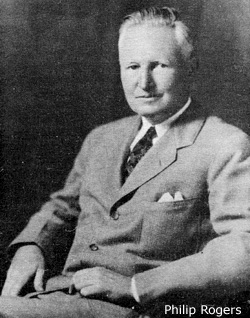

Philip Rogers and labor relations

The Millers Falls Company plants were non-union shops until the mid-1960s. Relations between company management and workers were, for the most part, quite good, and although there were periodic attempts at unionization, Philip Rogers’s hands-on approach to managing his workers was highly successful. Rogers was old school, practicing a type of management that labor historians refer to as paternalism. He knew the names and family circumstances of virtually all his workers, was proud of the importance of the company to the community, and was willing to take a substantial hit to the bottom line to avoid layoffs. In return, he expected loyalty, good work, and respect from his employees. Although paternalism has come in for criticism by some historians who consider it a self-serving deception perpetrated on workers by management, compared to the slash-and-burn tactics of the late twentieth century, the system as practiced by Millers Falls was fairly humane. Attempts to unionize the factories in 1950 and 1952 came to naught—most employees believed they were as well off as they would be with union representation. James Wooster, a personnel manager under Philip Rogers, later summed up the Millers Falls Company’s attitude towards its workers:

We were able to stay independent for so long because we had about the finest group of employees under one roof that I have ever seen. We had a good close relationship with our people of real respect and affection. ... We always thought that the three most important things in a job were job security, personal recognition, and money—in that order. I don’t know about nowadays, but back then I think we were absolutely right.(2)

Greenfield and Millers Falls were small towns, and Philip Rogers was a native; his approach to managing his workers was deeply rooted in this reality. Personnel decisions that might seem quirky today followed a logic that anyone familiar with small communities in 1950s would find easy to understand. A valued worker rumored to be considering a position at another firm might find himself being approached by a company official bearing the news of a job for his wife so that the family might enjoy a larger income while he remained at the plant. If accepted, the worker and his family would see a rise in income; the worker would understand his efforts were appreciated; and the Millers Falls Company would benefit by having earned the loyalty of two employees. The factories were places where a young man might work alongside his father, uncles and grandfather, and company management viewed such networks as evidence of sound labor practices. At Christmas, Rogers was known to walk through the factory, his pocket filled with cigars, offering one to any worker whose name he did not know. There is no report of his ever having to relinquish one of his smokes. Again, James Wooster:

...how a man feels is going to show up in production one way or another. For instance, if an otherwise good, solid worker got into debt, we’d often use our influence at the bank to help him get a good loan, or if there was a personal tragedy of some kind or another, we’d try to do what we could there, too. ... As far as hiring is concerned, you might say that we let the employees do the hiring for us. We had a lot of people in the shop that were in the same family and we liked it that way. A lot of times employees are the best judge of who should be hired because, after all, they have to work with them, don’t they?(3)

Cutting out the wholesalers

In the mid-1950s, the Millers Falls Company broke with the time-honored practice of using an established, nationwide network of consumer hardware wholesalers to distribute its tools and began selling directly to consumer hardware outlets. The change was the result of a recommendation by the company’s vice president for sales, a new hire whose previous experience had been with the Porter-Cable Machine Company, a smaller manufacturer in Syracuse, New York. Dismayed that hardware wholesalers were requiring deeper discounts for handling Millers Falls products than those of larger companies such as Stanley or Black & Decker, the new vice-president convinced the management team it would be more profitable to bypass the wholesalers entirely and market directly to retail outlets. Although the direct-to-retailer strategy had worked well for the smaller Syracuse company, it was an unmitigated disaster for the larger Millers Falls operation.(4)

At a time when much of the wholesale hardware business was based on face-to-face, interpersonal relationships, the Millers Falls Company informed its wholesalers—via wire service, on a Friday night, that it would no longer be doing business with them. A number of the wholesalers found themselves saddled with substantial investments in what had quickly become orphan merchandise. The incident was not forgotten, and consumer hardware wholesalers, with "memories like elephants," would remain reluctant to handle tools branded Millers Falls up into the 1970s. Then too, the decision put the company into the position of acting as its own wholesaler, making it necessary to establish a nationwide system of warehouses to service the retail outlets and to field a small army of additional salesmen. Because the new distribution setup lacked the efficiencies inherent in the traditional wholesaler system, distribution costs skyrocketed.(5)

The Union Tool Company

In 1957, Millers Falls acquired the Union Tool Company, a small firm of about 100 employees located at 48 East River Street in Orange, Massachusetts. Union Tool, in business since 1908, was a manufacturer of gauges, rules, squares, and machinists’ tools. The Millers Falls Company was especially interested in the operation’s combination squares—popular, mid-range products that were a good complement to its line of consumer hand tools. After the purchase, Millers Falls allowed Union Tool to operate with a great deal of independence, a situation that continued until the late 1960s when company management insisted on a greater integration with the larger operation. Millers Falls marketed the Union Tool Company’s products under the Union, Millers Falls, and Sears labels, and continued to operate the Union Tool factory until 1975 when the plant was sold, and the Union brand became inactive.(6)

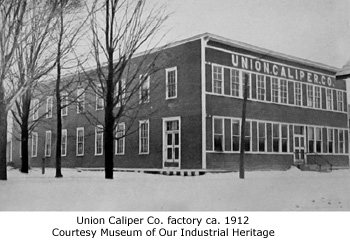

Founded in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, as the Union Caliper Company, Union Tool was organized by Emory E. Ellis in 1908 for the purpose of making machinist’s calipers and dividers. Ellis had previously been affiliated with the Sawyer Tool Manufacturing Company, a Fitchburg manufacturer of precision tools, where he served as plant superintendent and later became part owner. When Sawyer Tool was sold to Carl H. Hubbel in 1908, Ellis used the proceeds from his share to form the Union Caliper Company. Three years later, Union Caliper acquired a small line of precision tools from the Hill-Standard Manufacturing Company of Anderson, Indiana. The Hill-Standard line had become available when Hugh Hill, the company’s founder and president, redirected his business toward the manufacture of pedal cars for children and wheels for large toys. The purchase of the Hill-Standard tools brought some much-needed diversity to Union Caliper by adding thickness gages, machine vises, and feeler gages to the product line. Since Union’s board had moved the company to a larger site in Orange, Massachusetts, just prior to the transaction, the new activity was easily accommodated. The combined operations took up four times the floor space that had been available at the old Fitchburg location.

On November 21, 1913, the Union Caliper Company bought Bates Manufacturing Company, a Fitchburg-based producer of steel rules, combination squares, and hacksaw frames, for $5,000. Though Bates Manufacturing was a small operation, it maintained satellite shops in Leominster, Massachusetts, and Rutland, Vermont. John Clayton Bates, the company’s founder, had followed in Emory Ellis’s footsteps as superintendent of the Sawyer Tool Manufacturing Company but left the firm to set up Bates Mfg. when Sawyer moved its factory to Ashburnham, a small town near Winchendon. Although Bates sold his company to Union less than a year after he founded it, he stayed on as its supervisor after the buyout. In 1915, J.C. Bates moved to Orange to become manager of the Union Caliper Company and took the Bates measuring tool and hacksaw operations with him. Union would continue to use the Bates Manufacturing label on various products through the 1920s.

With Union Caliper making center punches, dividers, machine vises, hacksaws, measuring tools, nail sets, lathe accessories, and add-ons for automatic screw machines, the company name no longer reflected its product line. In 1916, Emory E. Ellis and the company’s directors changed the name of the business to Union Tool Company. Ellis died on November 11, 1924, at age fifty-four. During his years in tool manufacture, he had been instrumental in the development of twenty-six patents and brought some 700 tools to market.(7) He left behind a well-established, growing company. J.C. Bates continued as the firm’s manager, and by 1930, Union Tool was capitalized at $400,000 and providing jobs for one hundred employees. Under Bates’s stewardship, measuring tools became an increasingly important part of the Union operation, and there is evidence the company was supplying combination squares to Millers Falls well before the 1957 buyout. John Clayton Bates died on November 15, 1956—a year before the Millers Falls Company acquired the Union Tool Company.(8)

James N. Mitchell, the president of the Millers Falls Company, closed the Union Tool Company in 1975. Six months later, the factory and equipment were sold to Frederick W. Johnson and James Sogard, the principals of Adell Corporation, a small metal stamping business located next door. Taking as inspiration the first letters of their last names, the men organized Sojo, Inc., a manufacturer of small tools which they located in the former Union Tool building at 48 East River Street. Sojo manufactured hand drills, braces, planes, and other small tools, and much of the output was sold to the Millers Falls Company and re-branded. In 1985, Sojo was renamed Sogard Tool, a move reflecting Thomas Sogard’s position as sole stockholder. By this time, the Sogard payroll had dwindled to twenty, and employees and tooling were shared between Sogard Tool and Adell Corporation (forty employees) as the need arose. Sogard Tool eventually became a division of Echo Industries. As of this writing (2010), the Union Caliper/Union Tool factory is still standing.(9)

Illustration credits

- No. 714 plane: The finest planes in the world. Greenfield, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., [undated circular, ca. 1950].

- No. 525 keyhole saw: Rotatable blade keyhole saws. Greenfield, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., [undated circular, ca. 1950].

- No. 1414 hacksaw frame: Hand tools & precision tools. Greenfield, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., [undated catalog, but 1960].

- Philip Rogers portrait: Dyno-mite, November 1955.

- Union Caliper Company factory: Machinists tools of quality. Orange, Mass.: Union Caliper Co., [undated catalog , ca. 1912] in the collection of the Museum of Our Industrial Heritage.

- Linked push drill: Hand tools & precision tools. Greenfield, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., [undated catalog, but 1960].

- Linked hand drill: Hand tools, portable electric tools, hacksaws: catalog no. 49. Greenfield, Mass.: Millers Falls Co.,1949.

- Linked No. 300 hacksaw frame: Hand tools & precision tools. Greenfield, Mass. Millers Falls Co., [undated catalog, but 1960].

- Linked hand brace: Hand tools & precision tools. Greenfield, Mass.: Millers Falls Co.,[undated catalog, but 1960].

References

- Collura and the hand drills: U. S. Industrial Design, 1949-1950. New York: Studio Publications, 1949. p. 130. Collura and the hacksaw frame: United States Design Patent No. 140,810.

- The quote: Paul Jenkins. The Conservative Rebel: a Social History of Greenfield, Massachusetts. Greenfield, Mass.: Town of Greenfield, 1982. p. 213.

- The quote: Paul Jenkins. The Conservative Rebel: a Social History of Greenfield, Massachusetts. Greenfield, Mass.: Town of Greenfield, 1982. p. 213. On the practice of offering a position to a worker’s spouse: Telephone interview with Regis Garvey, president of Millers Falls in the late 1960s and early 1970s, January 4, 2005. The pocketful of cigars: Paul Jenkins. The Conservative Rebel: a Social History of Greenfield, Massachusetts. Greenfield, Mass.: Town of Greenfield, 1982. p. 226.

- Telephone interview, John J. Owen, Millers Falls Company president from 1962 to 1965, March 5, 2005.

- Two sources for this paragraph: Telephone interview, John J. Owen. March 5, 2005; e-mails, Dec. 14 and Dec. 16, 2004, James Mitchell, company president from 1972-1980. The “memories like elephants” characterization is courtesy James N. Mitchell.

- Telephone interview, John J. Owen. January 5, 2005.

- “Emory E. Ellis.” Western Massachusetts: a History, 1636-1925. vol. 3. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1926. p. 193.

- The information about Union Tool, the Union Caliper Company, Bates Mfg. Co.: Roger K. Smith. Letter, Athol Massachusetts, to Author, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, July 7, 2007; Orra L. Stone. History of Massachusetts Industries: Their Inception, Growth and Success. Vol. I. Boston: S. J. Clarke Publishing, 1930. p. 475-476; Kenneth L. Cope. Makers of American Machinist’s Tools: a Historical Directory of Makers and Their Tools. Mendham, N. J.: Astragal Press, 1994. p. 278.

- The research on the Union Tool Company, Sogard, and SoJo, based on city directories and newspaper clippings, was done by Steve Brackett, who reported to the OldTools discussion group: OldTools Message Archive, message nos. 139338 & 139025. Available at: http://archive.oldtools.org. Viewed July 15, 2007; Also: “Sogard Tool Company and Adell Corporation and United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE), Local 274.” Decisions of the National Labor Relations Board. v. 285-1044, case no. 1-CA-23967.