Millers Falls Company: 1873-1879

The Langdon miter box

In 1872, the Millers Falls Company became sales agent for the Langdon miter box, a tool enabling carpenters to accurately saw a piece of stock at any one of a series of pre-set angles. Patented by Leander W. Langdon on November 24, 1864, the cast iron miter box with its lockable adjustments was the first tool of its kind to enjoy widespread acceptance. The Langdon miter box was manufactured in Northampton, Massachusetts, by the Northampton Pegging Machine Company, an enterprise whose primary business involved the fabrication of hand-operated machines for attaching the soles of shoes with wooden pegs—a process cheaper than stitching.

When the creditors of the Northampton Pegging Machine advised it to go into bankruptcy in 1875, the treasurer of the operation, David C. Rogers, formed the Langdon Mitre Box Company and moved the business to Millers Falls.(1) Four years later, his son George E. Rogers, became Secretary of the Millers Falls Company. With members of the Rogers family serving as officers in both the Millers Falls and Langdon companies, the relationship between the firms was cozy. Millers Falls continued as sales agent for the Langdon products, and the miter boxes were manufactured at the Millers Falls plant. George Rogers eventually became the Treasurer, and later, Vice-President and General Manager of the Millers Falls Company. At the time, interlocking directorates were commonplace, and the arrangement must have been profitable for the principals of Langdon Mitre Box, for it was not until 1906 that the Millers Falls Company acquired control of the operation. The reputation of Langdon miter boxes became so well-established that the Millers Falls Company still capitalizing on the name in 1971 when it featured a Langdon miter box in its hand tools catalog.(2)

Drills

In 1873, Millers Falls added a breast drill to its offerings; hand drills followed in 1867. Forty years after these events, the company would boast it had been the first to add a chuck to a breast drill and had invented the hand drill. The claims were wildly inaccurate. The company based the breast drill claim on little more than being the first to add a Barber-style chuck to this type of tool. The firm had much to be proud of, however; its breast drills were well designed, and Millers Falls’ salesmanship made them the first to enjoy large scale market penetration. Factory-produced hand drills had been in use for at least three decades prior to the introduction of the Millers Falls products. The success of the company's eggbeater hand drills rested on Henry Pratt’s patent for a two-jaw, springless chuck that held small round-shanked bits securely. The Millers Falls Company labeled its new two-jawed bit holder the Star chuck, and as it had with the Barber chuck, sold it individually, for use on lathes. Given the popularity of its home hobbyist tools, the firm was ideally positioned to market the smaller drills, and they sold very well. The company's claims would have been on firmer ground had it stated it had developed the first hand and breast drills to enjoy mass market success.(3)

The lawsuits

Despite the addition of new products, the overall health of the Millers Falls Company continued to depend on the robust sales of its bit braces. The situation was not without its perils. Competitors routinely tried to circumvent patent protections by making slight changes to existing designs and claiming the result as a new development. One way for a patent holder to protect against this practice was to claim a flaw in the original patent resulted in a failure to reveal the true scope of the invention and have it re-issued in order to provide expanded coverage. Millers Falls combined this strategy, along with that of buying up the patents of its competitors, in an attempt to control the market for what it termed “grip-type” braces—bit stocks with shell-type chucks whose jaws brought pressure directly onto the shank of the bit. Though its attempts to obtain a re-issue for William H. Barber's 1864 chuck failed, the company was successful in its applications for the re-issue of several patents it had acquired along the way: the July 8, 1862, patent of James M. Horton for an auger handle with chuck, the April 16, 1867, bit stock patent of Clemens B. Rose and the February 19, 1867, patent of C. H. Stockbridge for a chuck. Coupled with its ownership of the rights to the early Charles H. Amidon and Albert D. Goodell chucks, the protections afforded its bit braces, especially its lucrative Barber Improved models, were substantial indeed.(4)

Company officers had good reason to worry about patent infringement. An early 1870s catalog included this message to customers:

There have been some complaints among jobbers that they are compelled to handle Barber braces without a reasonable profit. We know that this is true, but as yet cannot remedy the trouble. Other manufacturers are infringing our patents and some dealers are trading in the contraband goods. While this is done we cannot protect prices. As soon as the infringing goods were put on the market, we brought suit against the manufacturers, but did not think it wise to trouble the dealers.(5)

A note in the 1880 catalog indicates the Millers Falls Company had just obtained its third decree against a major brace manufacturer for patent infringement. The catalog was referring to the company's December 1879 victory against former partner Quimby S. Backus for a chuck he developed after leaving the operation. The Backus chuck was found to have infringed on the 1867 patent that the company acquired from C. H. Stockbridge. Just two years earlier, the company had won a suit against W. A. Ives and Company for infringing on Horton's auger handle and Amidon's 1868 chuck with its line of Ives, Ives Novelty, Centennial and Centennial Novelty braces. Although a collection of company letters in private hands makes reference to some sort of ongoing difficulties with brace manufacturer H. S. Bartholomew of Bristol, Connecticut, the identity of the third manufacturer has yet to be verified.(6)

Foot-powered treadle saws

The mid-1870s were a time of tremendous energy and creativity at Millers Falls. The firm had added bracket saws to the line in 1873, and sold 50,000 of them in the twelve months between August 1874 and August 1875. Its success in marketing hand-held saws provided inspiration for the development of the firm’s first foot-powered model in 1875. The new saw was a serious piece of equipment, weighing in at sixty-six pounds, able to operate at one thousand strokes a minute and capable of cutting through stock of up to three inches thick. The foot-powered scroll saw did well, but it was not until light-weight, amateur models were added to the catalog that the company stumbled onto a gold mine. Similar in principle to treadle sewing machines, the saws were a boon to weekend woodworkers, transforming the often tedious task of cutting decorative scrollwork into a pleasant diversion. The smaller saws were safe enough for older children to use without supervision, a happy circumstance rendering them capable of providing endless hours of entertainment to an entire family. Originally intended as a fill-in product to keep workers busy during the traditional fall downturn in sales, the saws were popular with hobbyists who created handicrafts and delicate scroll work during the winter, so demand picked up as the weather grew worse.

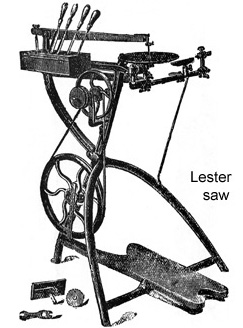

In 1877, the company introduced the light-weight Lester Saw and sold thousands of the tools within months. Designed by Edward Lester, the plant superintendent, the scroll saw featured a secondary circular blade, an emery wheel, a drill chuck and a small lathe, all of which could be mounted to its frame and powered by the treadle. A cheaper version of the saw, without the lathe and circular saw was offered as well, and as time passed, improvements multiplied. The frame was redesigned, a small blower was added to disperse sawdust, the breakable wooden treadle was replaced with cast iron, and the saw clamp was improved. With the improvements came changes to the name. The saw became the New Lester Saw and later, the Lester Improved Saw. A cheaper model without nickel-plated components was labeled the Lester No. 2. A display saw with silver-plated trim was manufactured for the window of Tallman, McFadden & Company. The deluxe finish proved to be a failure. The display model tarnished too easily and was soon replaced by one with nickel-plated components. The Lester saws proved so popular that other foot-powered, gadget-laden tools were added to the catalog.(7)

Edward Lester left the company shortly after developing his saw. In 1880, he joined A. W. Lyman and E. D. Severance in organizing the Lester & Lyman Manufacturing Company, an enterprise that set up shop on the Millers Falls canal in the building once housing Charles Amidon’s baby coach factory. Lester served as treasurer, and the business manufactured garden tools, household cutlery and such small hardware items as locks for window frames. Lester & Lyman relocated to Greenfield in 1884.(8) Lester also served as Treasurer of the German Harmonica Company, an entity with extremely close ties to Lester & Lyman. On July 1, 1880, the harmonica company leased a parcel of land and a waterpower privilege from the Millers Falls Company. The site was located on the Montague side of the river, opposite the Millers Falls Company’s plant, and the lease document noted the German Harmonica Company’s right to draw water was dependent on the pond’s level. Edward Lester signed for the harmonica company. Originally located in Shelburne Falls, the German Harmonica Company employed a dozen or so workers and was noted for successfully automating the production of the instrument. A fire—believed to have been deliberately set—destroyed the plant in October 1881.(9)

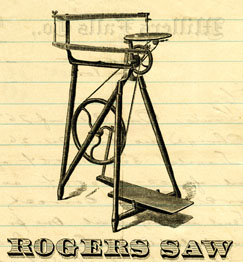

The Millers Falls Company brought out its first Rogers treadle saw in 1878. Named after George E. Rogers and designed to sell for less than the Lester, the saw had no provision for attaching a lathe or circular saw. Wooden components were painted rather than varnished, and trim was polished or japanned rather than nickel plated. Available for less than a third the cost of a Lester, advertisements noted:

It is not as good as our Lester Saw, but it is much better than any other cheap machine in the market.

The Rogers saw was replaced by the firm’s New Rogers fret saw a year after its introduction. The New Rogers, with it its stylish, horseshoe-shaped front legs, deserves special mention in that it became the most widely sold foot-powered jig saw of the era. Selling in the three to four dollar range and well-made for the price, the New Rogers hit a sweet spot in the market, and retained its leading position for decades. Although the Millers Falls Company advertised the New Rogers as the “best cheap saw in the business,” it went on to develop an even cheaper model, the Cricket. The Cricket was eight pounds lighter than the New Rogers, lacked a dust blower and sold for two dollars and fifty cents. Designed for the home market, the Millers Falls Company’s lightweight foot-powered saws got little respect from professional woodworkers and, indeed, were seen by one contemporary writer as fit only to “sell to boys and ministers of the gospel.”(10)

As the years passed, the company would exploit the bracket and scroll saw market in every manner possible. Starter kits including drills, gouges, hand-held fret saws and blades were sold for those not wanting a full blown treadle machine. Project patterns were added to the catalog and soon sold well enough that separate price lists with upwards of a thousand designs by firms such as Farrington & Company, Adams & Bishop, and Hope & Ware were published. Among the miscellaneous items that would eventually make an appearance in the specialized lists were feeding cups for mounting on intricately sawn bird cages and statuettes of a suffering Christ destined for elaborate scroll work crucifixes.

Royal C. Graves and the Boston office

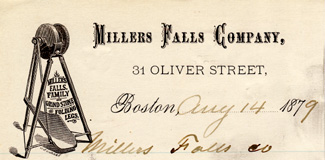

In the latter 1870s, the Millers Falls Company established a branch office in Boston. Located at 31 Oliver Street, the office was managed by R. C. Graves, an indefatigable salesman who traveled the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada in search of new accounts and was brother-in-law to company treasurer Levi J. Gunn. Although Graves had previously served as agent for Leonard Bailey’s line of Victor tools (in 1876), there is no evidence he represented manufacturers other than Millers Falls while operating the Boston office. A packet of forty-seven letters from Graves to the Millers Falls factory has survived.(11) Although most of the documents are simply orders for additional stock, Graves did not hesitate to criticize the merchandise, and his inherent impatience is evident in his frequent use of the phrase “Send me at once.” Among his comments:

We do not get any Rogers Saws yet ordered the 27th by telegram. We might as well be in China as here so far as getting goods is concerned. What is the trouble? (10/1/78)

Why don’t you send the O. S. Coach Vises I ordered more than a week ago. (6/5/79)

And if you are going to continue to use cast iron thumb screws on the clamp of Rogers Saw you might as well send me a gross. But I think you had better make a good screw on the start and save trouble. (10/1/78)

The hardware trade was competitive, and Boston was a regional, rather than national, center. R. C. Graves didn't dare let grass grow under his feet if he wanted to make his rent and pay his office assistant, John Mahoney. The network of wholesalers that was to dominate the twentieth century hardware trade did not yet exist, so building a dealer network was a laborious process done one client at a time, on a city-by-city basis. More than willing to leave New England if the trip meant additional sales, Graves convinced the home office to set up a saw exhibit at the Cincinnati Exposition of 1879. The company agreed to do so on the condition that Graves work with a local dealer who would be willing to take on the display merchandise after the show and work up the trade. On Henry Pratt’s recommendation, Graves arranged for a current Millers Falls customer—J. J. Watrous at 38 Arcade Street in Cincinnati—to take delivery of the goods and serve as agent for the sales generated. Graves traveled to Cincinnati to set things in motion, and Watrous staffed the display.(12)

The Millers Falls Company’s Boston office was discontinued in the early 1880s, and it would be decades before another regional office was opened. It is likely the office was set up to take advantage of the energy and talents of R. C. Graves (Royal Church Graves) and it was closed when he left to pursue other interests. Graves spent much of his long career in jobs related to the hardware trade. He and Levi Gunn were co-workers at the the Conway Tool Company and later on, the Greenfield Tool Company. In addition to working as sales agent for Millers Falls and Leonard Bailey & Company, he sold tools for Henry Disston & Sons, the Stanley Rule and Level Company, and in his seventh decade, for the Stratton Brothers Company in Greenfield. He died in 1910.(13)

Views of the plant in 1879

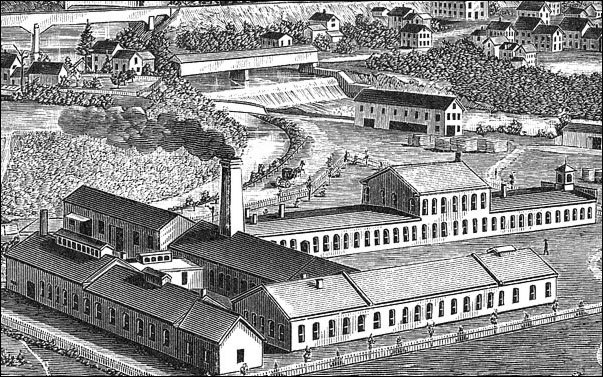

This bird’s eye view of the Millers Falls plant is taken from an 1879 book titled The History of the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts. It is rich in the amount of detail that rewards the careful observer.

This bird’s eye view of the Millers Falls plant is taken from an 1879 book titled The History of the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts. It is rich in the amount of detail that rewards the careful observer. The plant is nearly double the size of that shown in an 1873 view presented earlier in this narrative. A second floor has been added to part of the main building; substantial additions have been added to the rear; and the wing which parallels the main building has doubled in length. A cupola, retained through several remodelings, has been added to the front of the main building, and several storage sheds have been built along the river. The mill dam can be seen in the background, and immediately upstream is a covered bridge that was built in 1872 and connected Bridge Street to Gunn Street. Behind the covered bridge is the railway bed that enabled the efficient transport of material and finished product from the plant’s remote location. (The village of Millers Falls was a station on the Vermont & Massachusetts and the New London railroads.) The company’s canal can be seen running from the dam to the plant. Directly behind it, and to the left, is the flat-topped hill that was home to Amidon, Gunn, and Pratt Streets.

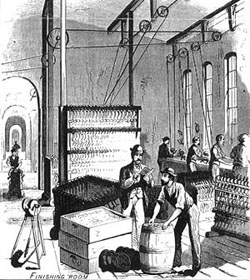

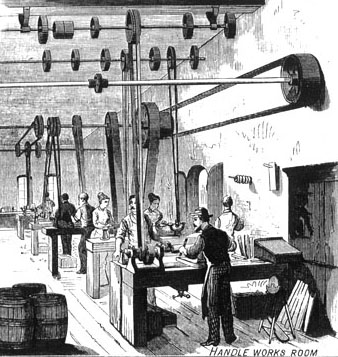

Several interior views of the Millers Falls plant were published on the cover of the popular journal Scientific American in the same year the bird’s eye view appeared in the Connecticut Valley book. Together with a few paragraphs of text, they tell us much about conditions inside the factory. To the degree possible, the exterior walls of the high-ceilinged rooms were pierced for windows to take advantage of natural light. An overhead system of belts and pulleys provided power to the grinders, lathes, drill presses, and milling machines used in manufacturing, and the company’s turbines could deliver up to three hundred horsepower to the network. Wooden floors were the norm, and the storage and use of solvents along with frequent sparks from the machines meant that fire was always a danger. The conflagrations experienced by the firm in its earliest years must have weighed heavily on the minds of its officers during construction planning as the main building was divided into six sections, each separated from the others by a heavy brick wall. A central corridor ran the length of the building and the doors dividing the sections were made of heavy iron and could be closed to prevent a fire from spreading. The series of arched doorways comprising the central corridor can be seen in the view of the finishing room at right. A close examination of the tools pictured shows braces, breast drills, wheels for treadle saws, and a foot-powered grinder.

The Millers Falls Company employed 150 souls at the time of the article. To have referred to them as men would have been a misstatement. As can be seen in the illustration at right, women began to take up positions in the plant early on, although they were doing what was considered light work. The two women are seen putting the final touches on turned wooden handles—most likely using a scraper or sandpaper. Just behind them can be seen an arched doorway with its fireproof iron doors. Since the ceiling in this room is flat—it is most likely on the ground floor in that part of the plant to which an upper story had been added. The officers of the Millers Falls Company did everything they could to make the plant as self-contained as possible. The works included an iron foundry, a brass foundry, blacksmith shops, a tempering shop, a machine shop, pattern and wood turning shops, a grinding shop, and a polishing shop. There were also inspection rooms, stock rooms, offices, and of course, privies.

The Greenfield Gazette and Courier considered the Millers Falls Company to be “in the front rank of the women’s labor movement” and noted the women at its lathes proved themselves “equal to their more muscular brothers.” The manufacturer used large quantities of rosewood and lignum vitae in the production of the wooden parts of its hand tools. Rough logs were purchased in New York and shipped to the plant to be sawn into the small pieces needed for tool handles. The use of these exotic woods was an expensive proposition. Scrap was not discarded, but was transformed into such products as pen holders, knobs, and buttons. One especially productive young woman was reported to have turned out 10,000 such buttons in a single day.(14)

The latest technology

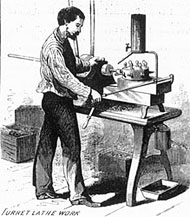

The company was proud of its machinery and did its best to keep abreast of current developments. The dapper worker in the illustration at left is pictured using a turret lathe. One of the uses to which the firm’s turret machines were put was the production of external shells for small universal chucks—products destined for eventual placement on hand drills, tool holders, or machinists’ lathes. A bar of iron would be put through the hollow mandrel of the lathe and turned, drilled, tapped, chamfered, finished, and cut off. The Millers Falls Company boasted a worker using such a machine could complete a chuck in five minutes. While, at first glance, the claim is accurate, it conveniently ignores the time and labor involved in manufacturing, assembling, and inserting the jaws—components necessary to make the shell functional. Be that as it may, the firm was proud of its capability for rapid and accurate production, touted it whenever possible and understood growth and survival depended on the ability to remain competitive.

It is tempting to romanticize the company’s nineteenth-century history in terms of Amidon’s overshot waterwheel and a handful of workers turning out eighteen braces a day, but the story of the Millers Falls Company is one of shrewd investment, innovative products, aggressive marketing, and the use of cutting edge technology.

Illustration credits

- George E. Rogers portrait: Hardware Dealers Magazine, v. 43, no. 253, January 1915.

- Lester Saw: Millers Falls Co., Millers Falls, Mass. [Catalog], 1878. Reprint 1992.

- Rogers Saw: Letter, Edward P. Stoughton to Millers Falls Company, Millers Falls, Massachusetts, 20 November 1878. (Verso of stationary)

- New Rogers Saw: Catalogue No. 35. Millers Falls, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1915.

- Letterhead for Boston Office: Letter, R. C. Graves to Millers Falls Company, Millers Falls, Massachusetts, 14 August 1879.

- Linked image of Langdon miter box: Catalogue 1887. New York: Millers Falls Company, 1887.

- Linked drawing of plant in 1873: Catalogue No. 35. Millers Falls, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1915.

- Birds-eye view of plant: History of the Connecticut River Valley in Massachusetts with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Philadelphia: L. H. Everts, 1879.

- Internal views of plant: Scientific American, March 22, 1879.

References

- “Business Interests.” Boston Daily Advertiser, February 03, 1875; “Millers Falls.” Gazette & Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) February 22, 1875.

- Langdon’s location within the Millers Falls plant: Telephone interview, John J. Owen, Millers Falls Company president from 1962 to 1965, March 5, 2005.

- Pratt’s chuck was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 194,109.

- The Horton re-issue, United States Letters Patent No. RE 4,187. The Clemens Rose re-issue, United States Letters Patent No. RE 6,212. The C. H. Stockbridge re-issue, United States Letters Patent No. RE 6,350.

- “Catalogs Provide Insight into Company Progress.” In: A Century of Experience: Millers Falls Company. Greenfield, Mass.: Greenfield Record, Gazette and Courier, August 13, 1968.

- H. L. Pratt. Letters to Millers Falls Company, Millers Falls, Massachusetts, spring-summer, 1879. Private collection.

- Edward P. Stoughton. Letter to Millers Falls Company, Millers Falls, Massachusetts, August 30, 1879. One of a packet of thirty letters, dating September 30, 1878-September 5, 1879. Seven addressed to L. J. Gunn, Tr. (Treasurer), one to George E. Rogers, (“Mr. Rogers”) and the remainder to general attention (“Gents”). Private collection.

- The information on Lester & Lyman: Pearl B. Care, Anastacia Burnett, and Doris A Felton. The History of Erving, Massachusetts, 1838-1998. Erving, Mass.: Erving Historical Society, 1988. p. 31; United States. Dept. of the Interior. Census Office. Reports on the Water-Power of the United States. Part 1. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1885. p. 113.

- Franklin County, Massachusetts. Register of Deeds. Book 348. p. 239. (Certified copy in the Greenleaf Collection, Museum of Our Industrial Heritage, Greenfield, Mass.) It is interesting to note the other signer of the deed was Levi Gunn, the Treasurer and a founder of the Millers Falls Company. The deed was witnessed by George E. Rogers, a justice of the peace and the Secretary of the Millers Falls Company. The deed was recorded by Franklin County Registrar Edwin Stratton, one of the owners of the Stratton Level Company, a supplier of wooden levels to the Millers Falls Company. See also: History of the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts: with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Philadelphia: L. H. Everts, Press of J. B. Lippincott & Company, 1879. vol. 2. p. 650; “Fire Record: Ravages of the Devouring Element in Various Localities.” The North American (Philadelphia, Pa.), October 8, 1881.

- Wood Workers' Tools: Being a Catalogue of Tools, Supplies, Machinery and Similar Goods Used by Carpenters, Builders, Cabinet Makers, Pattern Makers, Millwrights, Carvers, Ship Carpenters, Inventors, Draughtsmen, and all "Wood Butchers" not Included in the Foregoing Classification, and in Manufactories, Mills, Mines, etc. etc. Detroit, Michigan : Charles A. Strelinger & Company, 1897, p. 862.

- R. C. Graves. Letters to Millers Falls Company, Millers Falls, Massachusetts, May 13, 1878-September 8, 1879. Packet of forty-seven letters: two addressed to Levi Gunn (“Brother Levi”), one to George E. Rogers, (“Mr. Rogers”) and the remainder to general attention (“Gents”). Private collection.

- R. C. Graves. Letters to Millers Falls Company, Millers Falls, Massachusetts, July 11, 1879, July 14, 1879, July 17, 1879, August 9, 1879, August 18, 1879. Private collection.

- "Death of Royal C. Graves.” Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) June 18, 1910, p. 4.

- The information on the company’s use of tropical hardwoods and the role of women workers: “Millers Falls—Its Wonderful Growth and Promising Future” Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) November 4, 1872.