Millers Falls Company: 1962-1982

The Ingersoll-Rand buyout

By the early 1960s, the board of directors of the Millers Falls Company had become increasingly concerned about the future of the business. Company president Philip Rogers and chief financial officer Earl D. Holtby were ready to retire, and since the company’s shares were not actively traded, several elderly board members were concerned a takeover attempt might result in a series of sales at less than fair market price for the operation. Their fears were not entirely unjustified. Howard Butcher, a Philadelphia financier with a reputation for ruthlessness, was showing an interest in the company and controlled 10.2 percent of the shares, held in street name. The charge given to executive vice-president John J. Owen by the directors was straightforward: find a merger partner listed on the New York Stock Exchange so that shares in the new entity would be liquid, and ensure the deal would meet the approval of anti-trust regulators at Federal Trade Commission. (At the time, anti-trust regulations were stringent.)

In early 1962, as Owen was developing his list of merger prospects, a representative of the Ingersoll-Rand Company phoned Greenfield to express an interest in acquiring the Millers Falls Company. Ingersoll-Rand, a manufacturer of industrial tools and machinery, was looking for an easy entry into the consumer hand tool business and was on the rebound after failing in an attempt to acquire the Black & Decker Company. The Black & Decker deal, nearly complete, had been scotched when Robert Black, a brother to B & D founder S. Duncan Black, “spilled the beans to the press” after the per-share swap arrangement had been negotiated. Although a second choice, Ingersoll-Rand saw the Millers Falls Company as a viable alternative; its electric tools had a reputation for quality and world-wide name recognition.(1)

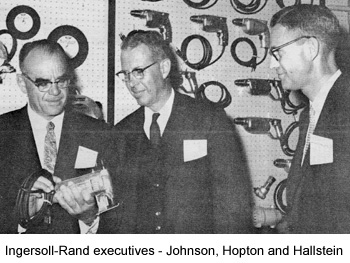

The primary negotiators for Ingersoll-Rand were: Lester C. Hopton, president; Robert H. Johnson, chairman of the board; and D. Wayne Hallstein, executive vice president. John Owen and the firm’s legal counsel, David Pokrass of Peabody, Brown, Rowley & Storey, a Boston law firm, represented Millers Falls. The resulting agreement specified an exchange ratio of one share of Ingersoll-Rand common stock for every 3.4 shares of Millers Falls stock outstanding. The deal was announced on May 17, 1962, and on that day, the 250,599 outstanding shares of Millers Falls Company stock were valued at $4,883,000.(2) The shareholders of the Millers Falls Company approved the agreement on June 15th by a margin of over ninety percent. Major shareholders voting for the arrangement included the Rogers family, owners of about 15 percent of the shares outstanding, and Howard Butcher, the Philadelphia financier.

John Owen, company president

The Ingersoll-Rand Company retired the Millers Falls senior management and chose John J. Owen—“Jack” to his friends and associates—as company president. Owen, the grandson of George Rogers, was the logical person for the job. At one time or another, he had held positions as assistant plant superintendent, advertising manager, assistant to the executive vice president, and executive vice president. His degree in mechanical engineering and experience as assistant plant superintendent provided a solid background in production; his experience as advertising manager ensured he had an understanding of the sales side of the operation. Owen would later recall, “Of course, it didn’t hurt that I knew the names of 500 non-union workers.”

The company Owen headed was not the aggressive, growing concern it had been earlier in the century. At the time of the buyout, Millers Falls employed some 600 workers—substantially fewer than the 1300 employed in the early 1950s—and its elderly, increasingly risk-averse board of directors had skimped on investment in plant and equipment. Ingersoll-Rand’s charge to Jack Owen was simple, if presumptuous: “We want you to be as big as Black and Decker in five years.” The feasibility of his task aside, the path, to Owen, was clear. Millers Falls needed to move away from the consumer hand tool business. Consumer hand tools were deeply discounted and profit-per-unit was relatively low. It was a high-volume business not well-suited to a small manufacturer—especially one with high distribution costs because it had alienated the consumer tool wholesalers. Owen believed the Millers Falls Company had the expertise to build hand tools for the industrial and professional market, that it had the reputation to sell them, and most importantly, that those tools, selling at much smaller discounts, would be more profitable on a per-unit basis.

As part of the Ingersoll-Rand family of companies, Millers Falls had access to resources unavailable to it as an independent operation. One of these was the ability to piggyback onto existing Ingersoll-Rand sales efforts. Even then, the company’s absence from the wholesale distribution network made its consumer hand tools vulnerable to subterfuge by competitors. James N. Mitchell, vice-President and distribution manager of P & C Tool Company, and later a president of Millers Falls, would recall:

When IR bought M.F. Co., I was working for a subsidiary of [Pendleton] Tool Co., also owned by IR. We sold wrenches, sockets, plumbing tools, screwdrivers, etc., to hardware stores through wholesale hardware distributors. This was the P & C brand. When M.F. was acquired, we added their line of hand woodworking tools, branded P & C. This created a war with Stanley because M.F. was almost out of this market as a result of going direct to the hardware retailer. Stanley told their wholesalers that they would lose the Stanley line if they handled the P & C line of woodworking tools. While illegal, they forced us out of the market within a year.(3)

Jack Owen was able to take advantage of Ingersoll-Rand’s considerable expertise in office and data management. Unbelievably, at the time of the buyout, the company was still paying its employees in cash. Every Friday, office manager Earl Brown and two woman payroll clerks would go to the local bank to make up the firm’s payroll envelopes—one for each employee—carefully counting and double-checking currency and coins before inserting them into the jackets. With the assistance of the new parent company, a data processing department was created, a new IBM computer was installed, and thereafter, workers were paid by check. The transition resulted in one memorable protest. An older employee, on receiving his first check, went to the payroll office with the complaint, “My check isn’t as much as my cash used to be.” An investigation revealed the worker’s foreman had been adding cash from his own pocket to the man’s payroll envelope each week. The worker, no longer as productive as he once had been, was accomplishing less than his peers. Since most of the firm’s production workers were paid by the number of jobs completed—a system referred to as piece work—the worker was earning less than others in his department. Not wanting a friend to feel that he couldn’t hold up his end of the work, the foreman was making up the difference.

Differences in corporate culture soon resulted in strained relationships between Ingersoll-Rand and Millers Falls management. Ingersoll-Rand was bottom-line driven; Millers Falls had traditionally put working relationships first, product second, and profit third. Things came to a head in 1965 when Ingersoll-Rand assumed responsibility for marketing Millers Falls products in Europe. Jack Owen traveled to Europe to close out the old sales operation—an entity known as Millers Falls Werkzeug Gmbh. The principal distributor for Millers Falls Werkzeug was Hans Christen, and Millers Falls had made a good faith arrangement to hold him harmless for the first $25,000 of his expenses should the arrangement be terminated. On his return to the United States, Owen visited Ingersoll-Rand headquarters and reported to executive vice-president D. Wayne Hallstein the task had been completed save for the writing of Christen’s settlement check. Hallstein listened and then advised Owen the check was unnecessary as the legal entity that made the agreement—Millers Falls Werkzeug Gmbh—was no longer in existence. When Owen insisted on honoring the agreement, Hallstein responded with a statement that Owen would remember with clarity some forty years later: “Jack, to succeed in our business, you have to have a little larceny in your heart.” The meeting ended in an argument with Owen on the verge of resigning, Hallstein on the verge of firing him, and the issue unresolved. Feeling ethically bound by the hold-harmless agreement with Christen, Owen returned to Greenfield and instructed treasurer Lucius Nims to write the settlement check. As Christen was planning to attend an upcoming hardware show in the United States, arrangements were made to present the check to him at the meeting. Nims and Christen, unaware of the sensitive nature of the transaction, had a photo taken of the event. It was subsequently published in an issue of Dyno-mite, the company employee magazine, where it was seen by a decidedly unhappy D. Wayne Hallstein.

On February 15th, 1966, just two months after Owen’s unhappy meeting with D. Wayne Hallstein, Millers Falls workers elected to unionize by a margin of 12 votes. The result of the election came as a blow to Jack Owen for it meant a United Electrical Workers representative would take his place in representing workers’ concerns to Ingersoll-Rand. Coupled with his very real sense of loss was an understanding that, without his role as mediator, he had become less valuable to Ingersoll-Rand. Six days after the union vote, John J. Owen turned fifty years old. The birthday qualified him for the Ingersoll-Rand retirement plan. (His years at Millers Falls before and after the merger were enough to vest him.) Owen retired and embarked on a successful second career as an educational fund-raiser. His first position was that of director of the capital campaign at Deerfield Academy. In 1968, he was offered the post of director of corporate relations at Yale University. After eight years at Yale, Owen moved on to the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, where he served for ten years as vice president for development.

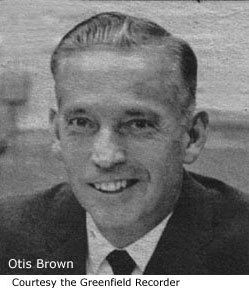

Otis E. Brown

John Owen was still company president when Otis Brown moved to Greenfield in December of 1965. Formerly vice-president of personnel for Ingersoll-Rand’s Pendleton Tool Industries division, Brown was assigned to the Millers Falls Company with the title of chief executive officer. At the time of Brown’s arrival, Owen was offered the title of chairman of the board but turned it down believing the president’s title put him in a stronger position to mediate differences between the company and workers prior to the upcoming unionization vote. Otis Brown was a protégé of Morris Pendleton, the long-term president of Pendleton Tool Industries both before, and after, its merger with Ingersoll-Rand. (Pendleton manufactured the well-known Proto line of tools.) A large stockholder in the Ingersoll-Rand Company by virtue of the sale of Pendleton Tool to the parent operation, Morris Pendleton was given a great deal of latitude in his work within the Ingersoll organization. Hoping to fold the Millers Falls operation into his own subdivision, he requested a special assignment as consultant to the management in Greenfield. He made a number of trips to Greenfield during Jack Owen’s presidency and when otherwise occupied, sent Otis Brown in his place.

Brown added the title of company president to that of CEO when Jack Owen retired. The company he inherited had grown during Owen’s years as president. Sales had increased from twenty-five to thirty-five million dollars per year, a modest program of updating equipment had begun, and the number of employees had increased from 600 to 1,000. Although the new line of “shock-proof” electric tools was selling well, the operation’s problems were profound. Despite his predecessor’s attempts to improve plant and equipment, the factories remained victims of an ongoing lack of capital investment and too often deferred maintenance. The Ervingside plant in Millers Falls had deteriorated to the point that forklifts had broken through the flooring, and the condition of the Wells Street plant in Greenfield was not much better. The equipment at the factories was antiquated, and at least one machine had become the object of a museum inquiry.(4)

The long-standing problems were not entirely of Ingersoll-Rand’s making, but the difficulties were exacerbated when the firm did little to improve the situation. Although Morris Pendleton—with forty-seven years’ experience in the tool business—spent a good deal of time with Otis Brown trying to iron out the problems, Ingersoll-Rand’s inability to make a profit left little incentive for further investment in the company. Frustrated and concerned about his health, Otis Brown retired in 1969 and moved to Arizona. Despite the efforts of Morris Pendleton, the Millers Falls Company remained independent of his Pendleton Tool Industries subdivision. Ingersoll-Rand would make periodic efforts to sell the Millers Falls Company but failed to find a suitable buyer.(5)

The Regis Garvey presidency

When Otis Brown retired, Regis F. Garvey, (Pat Garvey to his associates) became president of the Millers Falls Company. Formerly the operation’s Data Processing and Systems Manager, Garvey was determined to do whatever it would take to bring the company to profitability. His familiarity with the company’s computer system, comfort with numbers, and distance from production allowed him to develop a strategy for achieving profitability resting on two simple principles: reducing investment in the operation and increasing sales. “Reducing investment” meant cutting people, plant, and inventory. Thirty-five years later, Garvey would recall, “We weren’t making any money. We had 4,000 items in the line and factories in three locations when we started the surgery.”(6)

Garvey’s surgery was painful. The situation had deteriorated to the point that it was deemed necessary to close the Ervingside plant in Millers Falls—home to most aspects of the company’s electric tool production. The electric tool operation was relocated to the Wells Street plant in Greenfield, a move that ended the manufacture of hand-powered tools at that location. A number of the company’s hand-powered tools were dropped from the line; the production of others was outsourced; the production of still others was transferred to the Union Tool Company, the manufacturer of precision tools and squares acquired by the Millers Falls Company in 1957. The Union Tool Company subsidiary, which employed some ninety workers, had traditionally operated with a great deal of independence and was profitable—a situation allowing it to escape the ill effects of the retrenchment.

The best of the machinery from the old Millers Falls plant was transferred to Greenfield—a logical move, but one complicated by a last-minute surprise. The aged Ervingside plant, still powered by electricity from a dam and hydroelectric plant on the Millers River, was built to run at 550 volts rather than the standard 440, so a substantial retrofit of the Greenfield plant and the equipment was necessary. As part of the consolidation, the foundry at the Greenfield plant was shut down and converted into a storage room. The decision to close the foundry was based on simple economics: changes in technology had made it cheaper to purchase electro-melts from outside suppliers rather than to produce sand castings in-house. By the time the dust had settled, several hundred jobs were eliminated.

All Ervingside operations were moved to Greenfield except for “...the Woodworking Department, the Drop Forge and the Box Room, which were eliminated. In June 1970, a public auction was conducted and a quarter of a million dollars worth of equipment went piece-by-piece to the highest bidder. The following December, the unused Millers Falls factory was given to the Greenfield Community College Foundation with the possibility that it might be used as a vocational school. This never happened...”(7)

Garvey’s surgery would not have been successful if it had not been accompanied by a corresponding increase in sales. The operation became sales obsessed—pushing product to industrial distributors, automotive distributors, and hardware dealers with unheard of tenacity. The number of sales contacts skyrocketed; few stones were left unturned. The company even opened a pair of retail outlets, named “Tools, etc.,” in Springfield and Methuen, Massachusetts. The Millers Falls Company began showing a profit, and, after several years, employment rose once again to 900.

Chronically short of cash for meeting operating expenses, Millers Falls had borrowed millions of dollars from its parent company. Regis Garvey was especially proud of the day that the operation had amassed enough cash to pay off the debt. He marked the occasion by having a check for three million dollars drawn up and made payable to the Ingersoll-Rand Company. Taking the check with him to one of the regular meetings of Ingersoll-Rand executives, Garvey sat patiently at the conference table until the time came for him to make his report. Rising, he turned to Ingersoll-Rand’s chief executive, William L. Wearly, and announced, “Mr. Wearly, I present you with this check for 3 million dollars. It takes the Millers Falls Company out of debt.” Much to Garvey’s astonishment, his announcement was met with a nasal buzz. William Wearly had fallen asleep.(8)

Although Wearly had slept through Regis Garvey’s check presentation, the Millers Falls Company’s return to profitability did not go unnoticed. In 1974, Garvey was offered a promotion to the presidency of Pendleton Tool Industries by William Wearly and Wesley M. Dynes. Garvey accepted with more than a little reluctance—he enjoyed good working relationships with the survivors of the Millers Falls restructuring and considered Greenfield a fine place to raise a family. His instincts were good, for he did not find the situation at the higher profile Pendleton Tool operation to his liking. Ingersoll-Rand Company president D. Wayne Hallstein prided himself on the pressure he placed on division managers and considered them relatively expendable; as a result, turnover was high. Although Regis Garvey considered Hallstein to be one of the smartest people he’d ever met, he soon had enough of Ingersoll-Rand corporate culture. Two years after taking the Pendleton job, Garvey left the company to become the owner/manager of the Fox Run Resort and associated golf course in Ludlow, Vermont. It was a decision he never regretted.(9)

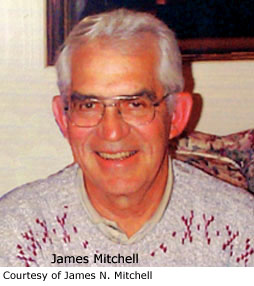

Jim Mitchell and the South Deerfield factory

James N. Mitchell, an Ingersoll-Rand manager with twelve years of experience, succeeded Regis Garvey as president of the Millers Falls Company. Mitchell moved to Greenfield from Los Angeles where he had served as national sales manager for Pendleton Tool Industries and as president of its export subsidiary. His appointment as company president was his second with the Millers Falls Company. Prior to his position with Pendleton Tool, Mitchell had been stationed in London, Canada, where he served for four years as president of Millers Falls Canada, Ltd.(10)

Although Jim Mitchell had some familiarity with the Millers Falls Company, his work with the operation had been from the sales end. Once he encountered the reality of the problems in Greenfield, he found himself “tempted to return to Los Angeles.” While Regis Garvey’s cuts had been necessary and the operation was now out of debt, huge challenges lay ahead if the company were to remain viable. Jim Mitchell recalls:

When I arrived at M. F. there were major problems. Everything was run down... Pat [Regis Garvey] had fired the whole Development Engineering Dept. to save money, and there were no new tools being designed. Two retail tool stores had been opened in malls in Massachusetts and were a real drag on earnings. The [Union] Tool Co., in Orange, MA, had been purchased, and the factory was out of the middle ages—overhead belts in the tool room, etc. The main product line was cheap machinists’ squares sold primarily to Sears at a loss. An earlier marketing decision to sell the MF Tool line direct to hardware stores rather than through wholesalers almost killed the market due to high distribution costs.(11)

By the time of Mitchell’s arrival, hand tools had become a minor, not particularly profitable part of the line, and most were purchased from outside sources. Oddly, however, the company’s expensive cast iron miter boxes, designed for use with a handsaw and made with purchased castings, were star money makers. Portable electric tools remained Ingersoll-Rand’s primary interest, and Mitchell re-established the Development Engineering Department to improve and refine the company’s heavy-duty electric tools. At one point during his tenure, electric impact wrenches—many of them labeled for W.W. Grainger—made up almost 20% of all sales. The operation continued making cutting tools—hand and power hacksaw blades, hole saws, and spade bits. Band saw blades were bought from the H.G. Thompson Co. and re-labeled. Jim Mitchell:

Solid high-speed steel was used for the cutting part of hole saws. This steel came in molts 3x4 feet square. When these were cut up to be milled for hole saws, there was a lot of expensive waste material. Someone got the bright idea of using this material to make wood-cutting spade bits. The cutting bits were formed, ground and then fitted into a slotted shank. They were joined to the shank by a pellet of silver solder heated in an induction coil which also hardened and quenched the tool steel blade. These were very cheap to make and would cut most anything.

M.F. was a leader in the metal-cutting area. High-speed steel hack saw blades and double edge power hacksaw blades were an interesting innovation. When these were made from very expensive tool steel the teeth became dull with use and were thrown away. M.F. developed a double edge blade. Teeth were milled on the back side of the blade and were set .005-.010 thinner than on the front. When the front teeth wore down the blade was turned over and the back teeth would add life to the blade. With the introduction of bimetal blades, this was dropped.(12)

Mitchell took a dim view of the company’s foray into the retail hardware business, and as he looked to streamline the operation, the retail outlets came in for some close scrutiny. He didn’t like what he found; the stores did not fit in with the company’s focus on portable, heavy-duty commercial and industrial tools.

The mall stores were opened in 1972, just before I arrived on the scene. Twenty or thirty additional were proposed even though the stores in Springfield, MA, and Methuen, MA, were a drain on profits from day one. One IR vice president was sold on the idea of retail. It took me over a year to get him to admit that these would never make money. Both locations were leased for ten years with Stop & Shop. When I closed the first one, the lessor took me to court to force me to keep the store open. The judge ruled in our favor but we were forced to continue paying on the lease (a lot of sub-leases) until we were able to buy out the balance.(13)

The Union Tool Company satellite, profitable in Regis Garvey’s time, had become a problem. Inefficient and antiquated, production costs were rising, and the declining demand for the sort of small hand tools produced by the unit put pressure on profits. In December 1975, James N. Mitchell closed the Union Tool Company, and six months later, the factory and equipment were sold to Frederick W. Johnson and James Sogard, the principals of Adell Corporation, a small metal stamping business located next door. Taking as inspiration the first letters of their last names, the men organized Sojo, Inc., a manufacturer of small tools that they located in the former Union Tool building at 48 East River Street. Sojo manufactured hand drills, braces, planes, and other small tools—much of the output was sold to the Millers Falls Company and re-branded.(14)

Perhaps the biggest problem facing the Millers Falls Company was its physical plant. By any definition of the term, the Wells Street factory was dilapidated. Metal sheeting covered weak spots in wooden floors; broken windows were unrepaired; waste from the nickel-plating operation was being dumped into the Green River watershed. Then too, the multi-story buildings with their aged freight elevators made for an extremely inefficient workflow. If the operation were to remain competitive, a new manufacturing facility would need to be built, and one of Mitchell’s first tasks would be to convince Ingersoll-Rand headquarters a new facility was needed.

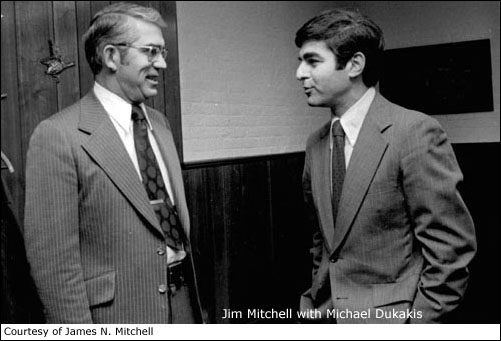

As he considered the situation in Greenfield, Mitchell became increasingly determined to move production to the Southern States. The Greenfield site was not large enough for the construction of a modern, one-story plant; Massachusetts taxes were high; and labor costs in the South were below the prevailing $5.20 an hour in Greenfield. In 1976, the search for a new site began in earnest. In October of that year, Massachusetts state governor Michael Dukakis visited Greenfield where he met Mitchell and learned of the relocation planning. Dukakis subsequently mentioned the pending move in a press conference, promising a state effort to keep the firm in Massachusetts but setting off widespread alarm in Greenfield. What had been rumored had become fact, and local citizens and union officials were outraged that a major employer with a century of tradition would be moved by Ingersoll-Rand. Jim Mitchell would later recall, “I was not the most popular person in town.”

Local government officials and business leaders, panicked at the thought of losing 600 jobs and an annual payroll of seven million dollars, quickly established a local development corporation. A package for financing a new plant was put together, and a list of possible sites was developed. Mitchell, concerned wages in Greenfield were too high, remained skeptical about the viability of a new factory. In December 1976, his attempts to negotiate a wage reduction with the company’s union—local 274 of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America—met with failure, and negotiations broke off.

...in January Mr. Mitchell took his case directly to the workers. Emotions were running high. Outside the plant, local activists were handing out leaflets denouncing the company. Inside...frightened workers weren’t producing effectively. Mr. Mitchell walked out onto the plant floor, stopped work, and called everybody together. “We told them face-to-face it wasn’t a bluff. We said that unless the union at least agreed to talk to us, we’d all lose...(15)

A week later, talks resumed, and three months after that, a contract with a cap on wage increases and a reduction in incentive pay was approved by rank-and-file union members. Property owners in Greenfield, however, remained unhappy with the siting options for the plant. Sensing economic opportunity, civic leaders of the neighboring town of Deerfield jumped at the project, securing state and federal funds to develop a thirty-acre site and putting together a package of tax-exempt industrial revenue bonds and reduced-interest loans from local banks. Jim Mitchell took the plan to the Ingersoll-Rand board; it was approved, and a new plant was built in South Deerfield, a few miles from the old Greenfield site. In 1978, 650 workers took up jobs in the new 250,000-square-foot facility.(16)

After moving to the South Deerfield facility, the old, multi-story buildings in Greenfield were of no use to Ingersoll-Rand. After several attempts to sell the plant, it was decided the best way to dispose of it was to donate it to the town of Greenfield. In November 1979, Mitchell offered the buildings to the town, and the offer was rejected. Mitchell made it clear that if the town didn’t accept the offer, the plant would be donated to the local junior college. After another meeting, the proposal was brought to a referendum vote and was narrowly accepted. The vote removed the plant from the tax rolls. Several years later, the town razed several of the oldest sections of the complex and converted the main structure to housing for the elderly. An attractive building, it was soon fully occupied.(17)

Selling out

In 1980, James N. Mitchell left the Millers Falls Company to become president of the Henry G. Thompson Co., a saw blade manufacturer in Branford, Connecticut. He was the last president of the Millers Falls operation. Ingersoll-Rand, having lost interest in hand and portable electric tools, did not name a new president to replace him. James Odell, a longtime Ingersoll-Rand engineer, was put in charge of day-to-day operations. Again, Jim Mitchell:

IR made a decision to focus on their basic business and get rid of both Proto Tools and the M.F. Co. Even when I was seeking approval to build the new facility, I ran into stiff opposition from the IR executive VP to whom I reported. He finally won. He came up as a salesman in the air tool division and wanted no part of the hardware market. The executive group at IR really didn’t understand our business and were not willing to invest any more resources. They used the same reasoning when selling Proto Tools to Stanley.

One of the IR V-Ps, who was retiring, was given the task of disposing of M.F. The factory and offices in Deerfield were sold to the owners of Rule Tool Co. All equipment and tooling for the electrical tool line was scrapped—with the exception of impact tools—which were transferred to another IR plant. Tooling for three or four other electric tools was sold to another tool co. By this time, the hand tool line was purchased from a number of other sources. Ray [Sponsler] was given the opportunity to purchase the name and hand tool inventory and sell to the hardware industry... I believe Rule also picked up the hole saw and hacksaw business and the Blu-Mol name.(18)

In the fall of 1982, Ingersoll-Rand sent the following announcement to its hand tool distributors:

On October 4, 1982, Ingersoll-Rand sold the Millers Falls builders hand tool business to a new company, the Millers Falls Tool Company. This is a newly incorporated New Jersey corporation and is not affiliated with Ingersoll-Rand. It will be headed by Ray Sponsler whose 26 years with Ingersoll-Rand in the tool business well qualifies him to carry on the Millers Falls hand tool commitment to quality and service. This sale of the hand tool unit of Millers Falls will allow Ingersoll-Rand to focus its resources on the improvement of the cutting tool and electric tool businesses. Of course, Ingersoll-Rand will continue to offer professional mechanics hand tools under the Proto and Challenger brand names.(19)

The new Millers Falls Company relocated to Alpha, New Jersey. The long, proud history of the western Massachusetts firm had come to an end.

Illustration credit

Ingersoll Rand executives with tools: Dyno-Mite, Oct. 1962.

References

- Unless otherwise specified, information on the Ingersoll-Rand buyout and Owen’s presidency: Telephone interviews, John J. Owen, January 5, 2005, and March 5, 2005.

- “Ingersoll-Rand Sets Acquisition”. New York Times. May 18, 1962. p. 45.

- E-mails to author, October 20, 2004, December 16, 2004, James N. Mitchell, company president, 1972-1980. In the this quote, I substituted the word “Pendleton” for Mitchell’s word “Proto.” Ingersoll-Rand employees frequently referred to Pendleton Tool by the name of its best known brand—Proto Tools. The P & C Hand Forged Tool Company of Milwaukie, Oregon, was acquired by Pendleton Tool in early 1941. (Pendleton Tool was named Plomb Tool Company at the time.) P & C took its name from its founders, John Peterson and Charles Carlborg, who had organized the business in 1920.

- On the forklift problems and museum inquiry: Greenfield Popular Union. More of the Same: Millers Falls Tool Threatens to Runaway. Turners Falls, Mass.: Greenfield Popular Union, 1977.

- On Pendleton’s assistance to Otis Brown: E-mail to author from James N. Mitchell, October 20, 2004.

- The quote and, unless otherwise specified, the information on Garvey’s presidency: Telephone interviews with Regis Garvey, January 4, 2005, and April 21, 2005; “MF Co. Names New President.” Greenfield Recorder Gazette. (Greenfield, Mass.) 1973. (from newspaper clipping lacking month and date of publication)

- The quote: Pearl B. Care, Anastacia Burnett, and Doris A Felton. The History of Erving, Massachusetts, 1838-1998. Erving, Mass.: Erving Historical Society, 1988. p. 23.

- The quote: Telephone interview with Regis Garvey, April 21, 2005.

- On Ingersoll-Rand and division managers: “Banquet Days for Capital Goods Producers.” Business Week. June 22, 1974, p. 75.

- Unless otherwise specified, information on Jim Mitchell’s presidency: Series of nine e-mail messages to author from James N. Mitchell, September 29, 2004 through December 16, 2004.

- The quote: E-mail to author from James N. Mitchell, Oct. 1, 2004.

- The quote: E-mail to author from James N. Mitchell, Dec. 12, 2004.

- The quote: E-mail to author from James N. Mitchell, Oct. 20, 2004.

- The research on the Union Tool Company and SoJo, based on city directories and newspaper clippings, was done by Steve Brackett, who reported to the OldTools discussion group: OldTools Message Archive, message nos. 139338 & 139025. Available at: http://archive.oldtools.org. Viewed July 15, 2007.

- The quote: “Bucking the Trend: a New England Town Stops a Big Employer from Moving South.” Wall Street Journal. January 9, 1978, p. 1, 22.

- Planning for (and building of) the new plant: “Bucking the Trend: a New England Town Stops a Big Employer from Moving South.” Wall Street Journal. January 9, 1978, p. 1, 22. For the union’s side of the story: Greenfield Popular Union. More of the Same: Millers Falls Tool Threatens to Runaway. Turners Falls, Mass.: Greenfield Popular Union, 1977. For an analysis of local politics at the time of the controversy: Paul Jenkins. The Conservative Rebel: a Social History of Greenfield, Massachusetts. Greenfield, Mass.: Town of Greenfield, 1982. p. 253-256.

- Letter to author from James N. Mitchell, undated. (received May 13, 2005). In it, the author refers to himself as “Mitchell.” As I’ve made several minor edits, I have not treated the text as a quote.

- The quotes: E-mail to author from James N. Mitchell, Dec. 14, 2004, Oct. 12, 2004.

- The quote: “Subject: Hand Tool Announcement.” Ingersoll-Rand. Power Tool Division. Circular Letter #M-496. October 4, 1982.