Gunn & Amidon: 1861-1868

Wash wringers

Levi J. Gunn and Charles H. Amidon were in their early thirties when they decided to go into business for themselves. Employees of the Greenfield Tool Company, they hoped to build wringers for squeezing water from freshly laundered clothes. Their employer manufactured wooden hand planes, so the men were well-versed in the technologies of the day and understood the problems inherent in running a factory. Gunn, a blacksmith's son, had been involved with tool manufacture since his youth; Amidon, a shoemaker’s son, was a born innovator. The enterprise began modestly. Employees assembled wringers in rented rooms at a rundown steam mill near Greenfield’s first railway station. Under-capitalized and unsure of success, Gunn and Amidon chose to remain with the Greenfield Tool Company and tended to the business part time. In June 1861, the fledgling operation nearly foundered when the steam mill burned.(1)

Levi J. Gunn and Charles H. Amidon were in their early thirties when they decided to go into business for themselves. Employees of the Greenfield Tool Company, they hoped to build wringers for squeezing water from freshly laundered clothes. Their employer manufactured wooden hand planes, so the men were well-versed in the technologies of the day and understood the problems inherent in running a factory. Gunn, a blacksmith's son, had been involved with tool manufacture since his youth; Amidon, a shoemaker’s son, was a born innovator. The enterprise began modestly. Employees assembled wringers in rented rooms at a rundown steam mill near Greenfield’s first railway station. Under-capitalized and unsure of success, Gunn and Amidon chose to remain with the Greenfield Tool Company and tended to the business part time. In June 1861, the fledgling operation nearly foundered when the steam mill burned.(1)

The fire turned out to be the proverbial blessing in disguise. The operation’s wringers were selling well, so Gunn was able to find the backing needed to revive the enterprise and build a small factory. The situation looked promising enough to convince the men the risks inherent in leaving Greenfield Tool were worth the potential reward.(2) Their selection of a marginal plant site on Cherry Rum Brook in the city's North Parish was due as much to the modest capitalization of the enterprise as to poor judgment. Well aware they were working with a smaller stream, the men planned to power the plant with an overshot water wheel—a setup best suited for deriving energy from a modest flow. Designed and built by Amidon, the wheel transmitted power to the factory’s machinery by means of thick rope rather than expensive leather belting.

The road to the plant was laid out in spring of 1862, and construction of the factory began soon after. Ashley Holland, a machinist and early investor, built the stone dam.(3) In the fall, the United States Patent Office approved Charles Amidon’s application for a new clothes wringer. Production began prior to the final issue of the patent, and the firm demonstrated Amidon’s wringer at the New York State Fair yet that year. The wringer won a first-place award, an event followed in 1863 by awards at the Pennsylvania State Fair, the Syracuse Mechanics Fair, and the Maryland Institute.(4) Gunn’s barn was pressed into service as the operation’s warehouse. It was a cost-effective arrangement but one with unforeseen consequences when the structure burned to the ground, taking an uninsured inventory worth $300 with it. By August 1863, a short fifteen months after the road to the plant was platted, twenty thousand Amidon wringers were in customers’ hands.

The success of the Amidon wringer necessitated an expansion of the plant. Gunn brought Charles Amidon in as full partner at this time and published a notice in the December 7, 1863, Gazette and Courier.

Having just completed a large addition to my factory, which is located about one and one-half miles north of Greenfield village, to accommodate the rapid increase of manufacture of AMIDON’S PATENT WRINGER, I have this day associated with CHARLES H. AMIDON, (patentee of the above-named wringer,) as partner in business, which will be hereafter conducted under the name of GUNN & AMIDON.

Although its dam washed away in 1864, Gunn & Amidon prospered and added a new product. John S. Lash of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, had patented a wringing and washing machine in 1862. Gunn & Amidon modified the machine, replacing the Lash wringer with Amidon’s, and marketed the result as “The Washing-ton Machine.” Advertised as the “cheapest, simplest and most perfect machine in the world,” much was made of the fact that the unit’s Amidon wringer operated without cog wheels and could be trusted to be gentle on clothing. Press notices advised that a bank bill could be “placed in the machine with a dozen dirty collars and the collars washed clean without doing the least injury to the bill.” Eager to leave no promotional stone unturned, the partners’ ads boldly included the challenge, “We defy anyone to produce a better.”(5)

Although its dam washed away in 1864, Gunn & Amidon prospered and added a new product. John S. Lash of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, had patented a wringing and washing machine in 1862. Gunn & Amidon modified the machine, replacing the Lash wringer with Amidon’s, and marketed the result as “The Washing-ton Machine.” Advertised as the “cheapest, simplest and most perfect machine in the world,” much was made of the fact that the unit’s Amidon wringer operated without cog wheels and could be trusted to be gentle on clothing. Press notices advised that a bank bill could be “placed in the machine with a dozen dirty collars and the collars washed clean without doing the least injury to the bill.” Eager to leave no promotional stone unturned, the partners’ ads boldly included the challenge, “We defy anyone to produce a better.”(5)

The men found themselves in a cutthroat business. Although wash wringers had become commonplace, they were easy to manufacture. Competitors were legion. The much-advertised Universal Clothes Wringer, marketed by Julius Ives & Company of New York City, outsold the Amidon two-to-one in 1863. The Universal used a cog arrangement to transfer motion from the lower roller to the upper—a feature Ives promoted. Gunn and Amidon countered by referring to their product as the “anti-cog wheel clothes wringer,” intimating that cog arrangements were unreliable and prone to breakage.

While Amidon’s wringer sold well enough, enhancements were required to keep abreast of the market. In spring of 1865, Charles H. Amidon patented an improvement to his wringing machine. His new chain-driven wringer allowed for a more reliable roller movement and consistent pressure on laundry items. Mindful of the need to promote the product, the firm added an illustration of “Amidon’s New Improved Clothes Wringer” to its stationery and envelopes. Gunn, Amidon & Co. also placed an ode to the new ringer in the Greenfield Gazette and Courier. While not exactly a literary masterpiece, an examination of the verses reveals that, except for subtlety, there is little new in the psychology of advertising.(6)

The partnerships established by Franklin County businessmen were not particularly long-lasting. Often created to attract capital or acquire goods and services, they were formed and abandoned with relative ease as personal or business circumstances warranted. On March 15, 1865, Elijah R. Saxton became a partner in the firm, and the enterprise was renamed Gunn, Amidon & Company. His tenure with the firm was not to be a lengthy one. Saxton left just fourteen months later. By contemporary standards, the duration of the term was unremarkable; the local paper carried frequent announcements of such couplings and uncouplings. After his departure, the firm went back to its original name, and Saxton moved to Buffalo, where in 1870, he reported to a census taker that he worked at a steam forge.(7)

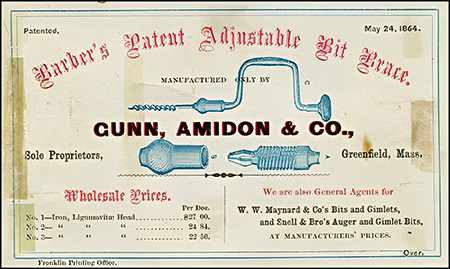

Barber braces

A product the partners had begun manufacturing in 1864 soon diminished the operation’s dependence on Amidon’s improved wringer. On May 24th of that year, Greenfield native William H. Barber had patented a chuck ideally suited for use on bit braces. Barber, a machinist who built muskets for the Union Army in Windsor, Vermont, convinced the partners his invention had the potential to do well.

A product the partners had begun manufacturing in 1864 soon diminished the operation’s dependence on Amidon’s improved wringer. On May 24th of that year, Greenfield native William H. Barber had patented a chuck ideally suited for use on bit braces. Barber, a machinist who built muskets for the Union Army in Windsor, Vermont, convinced the partners his invention had the potential to do well.

Although it is unlikely Gunn and Amidon fully understood the revolutionary significance of the Barber design, they were astute enough to purchase the rights from him. Barber’s shell-type chuck became the standard by which developments in bit-holding technology were judged. Production began at eighteen braces per day. Business cards were printed, the company marketed the braces aggressively, and they sold well. Elijah Saxton's 1865 decision to leave the company would cost him dearly. The profitability of the Barber brace became the foundation on which the Millers Falls Company was built.

Given the tool’s success, it was inevitable that Charles Amidon would toy with brace designs of his own. His first, patented in 1865, consisted of a shell-type chuck with its jaws attached to a floating socket block. His second, patented in 1867, used an eyebolt and wing nut to hold a bit in place. Few examples of either tool survive.(8) Sales of the Barber brace, however, continued to exceed expectation. By 1867, production at Gunn, Amidon & Company had risen to several hundred units per week.

The partners chose to de-emphasize the wringer business. When Amidon patented a new four-gear wringer that spring, he sold the rights to the Bailey Washing and Wringing Machine Company of Woonsocket, Rhode Island. Soon after, Gunn & Amidon quit building wringers. The partners kept a hand in the business by maintaining a repair operation. In addition to providing parts and service for the Amidon wringers, they repaired Novelty and Champion machines as well. The firm held the local rights to a process for replacing the rubber surfaces of wringer rollers and could re-surface most brands upon request.(9)

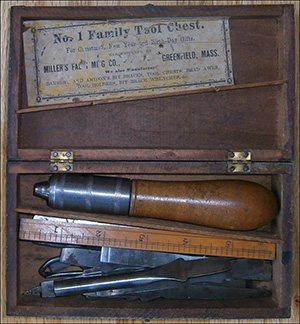

Charles Amidon kept experimenting and hit a home run with the chuck he patented on January 14, 1868. A rework of Barber’s design, it was outstanding in its simplicity and function. In addition to being cheaper to manufacture, the chuck's jaws provided a secure grip on a wider variety of shanks. Amidon’s Barber Improved Brace became the operation’s best-selling tool and had as much to do with the company’s prosperity as any single product. The introduction of the improved brace coincided with that of another device that would do quite well for the company—the tool holder. The firm’s tool holder consisted of a hollow handle fitted with a chuck into which various bits, chisels, and saw blades could be mounted. When not in use, the attachments were stored in the hollow of the handle. Minus its accessories, the tool holder was marketed as a deluxe file handle. A handy item around the house, the tool holder’s gadgetry proved irresistible, and it soon became the basis for the firm’s Family Tool Chest. Consisting of little more than a small wooden box, a tool holder, and a dozen or so attachments, the Family Tool Chest strove mightily to live up to its name.(10)

Charles Amidon kept experimenting and hit a home run with the chuck he patented on January 14, 1868. A rework of Barber’s design, it was outstanding in its simplicity and function. In addition to being cheaper to manufacture, the chuck's jaws provided a secure grip on a wider variety of shanks. Amidon’s Barber Improved Brace became the operation’s best-selling tool and had as much to do with the company’s prosperity as any single product. The introduction of the improved brace coincided with that of another device that would do quite well for the company—the tool holder. The firm’s tool holder consisted of a hollow handle fitted with a chuck into which various bits, chisels, and saw blades could be mounted. When not in use, the attachments were stored in the hollow of the handle. Minus its accessories, the tool holder was marketed as a deluxe file handle. A handy item around the house, the tool holder’s gadgetry proved irresistible, and it soon became the basis for the firm’s Family Tool Chest. Consisting of little more than a small wooden box, a tool holder, and a dozen or so attachments, the Family Tool Chest strove mightily to live up to its name.(10)

By 1868, the principals of Gunn & Amidon had to come to understand that the business was at a crossroads. Although the firm’s patented bit braces were selling well and payroll had grown to twenty workers, the factory was inadequate to meet the demand for its products. Cherry Rum Brook did not produce enough waterpower to support a larger operation, so on-site expansion was not feasible. The partners made do by installing an eight-horsepower steam turbine to provide against the inevitable periods of low flow, but there was no substitute for the cheap and efficient power of falling water. A new location would need to be found and another plant built. Certainly, Charles Amidon and Levi Gunn did not anticipate the site they had selected in 1862 would turn out so poorly.

Illustration credits

- Gunn portrait: Historical Society of Greenfield (Massachusetts). (This photograph of the original portrait is copyright of the author.)

- Washing-ton machine: Gazette and Courier. Greenfield, Mass., December 19, 1864.

- Early Barber brace: author’s photo.

- Gunn & Amidon business card: courtesy Roger K. Smith.

- Family Tool Chest: author's photo.

- Linked wash wringer drawings: United States letters patents.

- Linked Barber chuck drawing: Illustrated Catalog of Hardware and Tools. Boston: A. J. Wilkinson & Co., ca. 1867.

References

- Basic information for this chapter is from: Allan D. Adie. “75 Years of Honest Endeavor.” Dyno-mite, December 1943, p. 18-19 & 22; Gazette and Courier. (Greenfield, Mass.) January 1862-Dec. 1868; “The Millers Falls Co.” Hardware Dealers Magazine, January 1915, v. 43, no. 253, p. 107-117.

- On the business before 1862: Paul Jenkins. The Conservative Rebel: a Social History of Greenfield, Massachusetts. Greenfield, Mass.: Town of Greenfield, 1982. p. 126.

- Ashley Holland was one of the witnesses to Charles Amidon’s application for his 1862 wringer patent. It was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 36,761.

- Information about the promotion of Amidon’s first wringer is from advertisements: Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) August 24, 1863, and November 11, 1863.

- The Lash washing machine was awarded United States Letters Patent no. 36,658. Information on the Gunn & Amidon version is from an advertisement: Gazette and Courier ((Greenfield, Mass.) December 19, 1864.

- Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) July 31, 1865. Charles Amidon’s improved wringer was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 47,079.

- Notices of Saxton’s arrival and departure: Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) March 27, 18655, and June 25, 1866. Example of a short partnership: Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) December 18, 1871.

- William H. Barber’s chuck was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 42,827. See also the biography of his son, James T., in: The History of Eau Claire County, Wisconsin, Past & Present: Including an Account of the Cities, Towns and Villages of the County. Chicago: C. F. Cooper, 1914. p. 643-645. Amidon’s chuck with the floating socket block was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 50,214. Amidon's eyebolt brace was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 64,931.

- Amidon’s four-gear wringer was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 64,932.

- Amidon’s Barber Improved Chuck was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 73,279.