Millers Falls Company: 1890-1900

Saws and the saw business

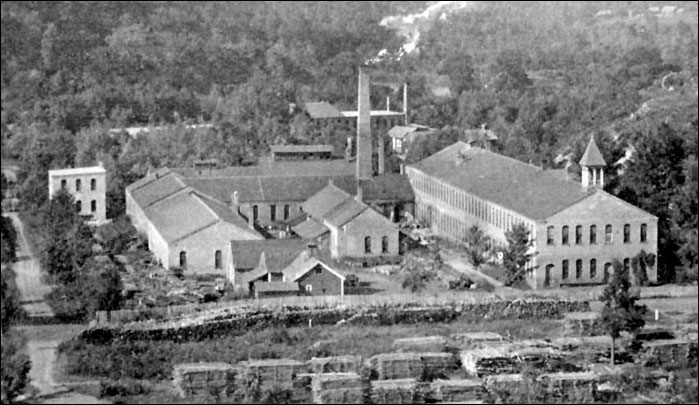

This is the Millers Falls plant as it appeared in 1891. It is taken from an illustration that appeared in a book entitled Picturesque Franklin County, published in that year by Wade, Warner & Company of Northampton. Shown is the side of the plant facing the Millers River, and stacks of logs and lumber are seen in front of the buildings. The main building, on the right, is now two stories for its entire length, and several new additions and smaller structures can be seen. The company was able to report it had 75,000 square feet under roof. The town which had sprung up around the plant now numbered between eight and nine hundred residents, and the operation itself included some two hundred workers—fifty more than in 1879. While George Rogers and Levi Gunn kept an eye on the plant, Henry Pratt and Edward Stoughton worked out of the new company office at 93 Reade Street in New York City. At times referred to as a warehouse, the new location, secured in 1887, was two blocks from the old office at 74 Chambers Street and consisted of “a full store with basements.” The New York office remained at the Reade Street address until 1898 when it was relocated to 28 Warren Street.

In a short business notice in the October 1890 issue of The Manufacturer and Builder, the Millers Falls Company was reported to have laid claim to the distinction of being the largest manufacturer of carpenters’ and machinists’ saws in the world. There was some truth to the assertion. The export side of the company’s business was booking orders for 150,000 saws with some regularity, and a 200,000 saw order had been shipped. The firm reported total saw sales running into the millions of units. Considering that the company sold hand-powered bracket, frame, and scroll saws; hack saws; treadle saws; butchers’ saws; and de-horning saws, and that it sold massive quantities of saws to accompany Langdon miter boxes, it is possible that Millers Falls was the leading saw seller in the world. It would be prudent, however, to consider that the company may have chosen to blur the line between the terms “manufacturer” and “seller” in order to make the most of its story.

In a short business notice in the October 1890 issue of The Manufacturer and Builder, the Millers Falls Company was reported to have laid claim to the distinction of being the largest manufacturer of carpenters’ and machinists’ saws in the world. There was some truth to the assertion. The export side of the company’s business was booking orders for 150,000 saws with some regularity, and a 200,000 saw order had been shipped. The firm reported total saw sales running into the millions of units. Considering that the company sold hand-powered bracket, frame, and scroll saws; hack saws; treadle saws; butchers’ saws; and de-horning saws, and that it sold massive quantities of saws to accompany Langdon miter boxes, it is possible that Millers Falls was the leading saw seller in the world. It would be prudent, however, to consider that the company may have chosen to blur the line between the terms “manufacturer” and “seller” in order to make the most of its story.

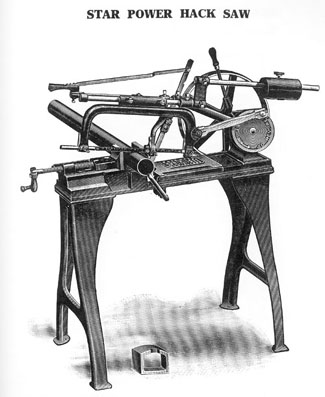

Millers Falls leveraged its relationship as sales agent for Clemson Brothers hacksaw blades into a profitable line of Star brand hacksaw frames. Steel, cast iron and wooden frames were available, and saws with extendable frames and re-positionable blades were developed. Although the frames were promoted heavily, the line’s success rested on the quality of Clemson’s blades. An advertisement in the January 16, 1897, issue of Scientific American noted:

Our Star Hack Saws are now used in nearly all Ironworking Shops the world over. They are equally useful for farmers and men in all departments of life. They will cut iron and wood equally well. A nail does not dull them at all. One blade, which costs five cents, will cut off an inch square bar of iron 200 times without sharpening. We have cut off such a bar 387 times with one blade.

The company credited Henry L. Pratt with the original idea for its Star power hacksaw.(1) The first experimental machine consisted of a crankshaft mounted on a lathe and attached to an arm with a hacksaw mounted on it. A wooden-frame model followed, and metal-frame machines became available as early as 1891. Star power hacksaw machines were the featured exhibit at the Millers Falls booth at the Columbia Exposition in Chicago in 1893. The manufacturer wisely chose to demonstrate the saw in action. Onlookers were amazed to watch a machine sawing through a metal bar at a steady forty-five strokes a minute and then stopping automatically when the cut was completed. Although the rate of cutting was not speedy, company representatives were quick to point out that automated sawing was quicker than using a lathe or planer and far quicker than heating a piece and cutting it with a blacksmith’s hack. The Star power hacksaw received international exposure at the exposition, and one English shop straight away ordered one hundred of them. Oddly, the firm began almost immediately to get requests for hand-cranked hack sawing machines. To accommodate the demand, a heavy drive wheel with a hand crank was designed for the machine and made available at extra cost. Apparently, the company had no problem finding customers who were willing to pay a premium in order to operate their power hacksaws by hand.

William McCoy’s chucks

During the 1890s, a long-standing company employee, William H. McCoy, patented improvements to the two classic chucks mounted on the premium Millers Falls drills and braces. McCoy added a spring to the jaws of the Barber Improved chuck in 1890. The new, self-opening jaws remained the hallmark of the company’s better braces until supplanted by the first truly universal jaws in 1907. McCoy also redesigned the company’s Star chuck in 1896, increasing the number of jaws from two to three and improving its grip on round shanks. The jaws in the new Star were held in place by pins that moved back in forth within recesses cut into the chuck’s socket, remaining in easy alignment when tightened on the shank of a drill. Relatively inexpensive to manufacture and highly reliable, McCoy’s three-jaw chuck was an outstanding piece of work and provided a starting point for what was to become one of the most extensive lines of hand drills ever offered. In addition to his work with chucks, McCoy re-designed the company’s angular bit stock in 1897.(2)

During the 1890s, a long-standing company employee, William H. McCoy, patented improvements to the two classic chucks mounted on the premium Millers Falls drills and braces. McCoy added a spring to the jaws of the Barber Improved chuck in 1890. The new, self-opening jaws remained the hallmark of the company’s better braces until supplanted by the first truly universal jaws in 1907. McCoy also redesigned the company’s Star chuck in 1896, increasing the number of jaws from two to three and improving its grip on round shanks. The jaws in the new Star were held in place by pins that moved back in forth within recesses cut into the chuck’s socket, remaining in easy alignment when tightened on the shank of a drill. Relatively inexpensive to manufacture and highly reliable, McCoy’s three-jaw chuck was an outstanding piece of work and provided a starting point for what was to become one of the most extensive lines of hand drills ever offered. In addition to his work with chucks, McCoy re-designed the company’s angular bit stock in 1897.(2)

Auger handles

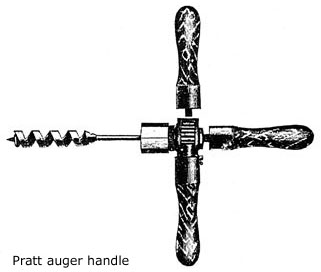

The Millers Falls Company’s 1897 catalog is notable for its four T-auger handles—two of them labeled as Pratt’s, one as Rogers’ and another as Gunn’s.(3) The T-auger handles used by most workmen were simple tools, being little more than a stick with a square hole in the center for holding the bit. In the hands of a burly workman, the device is surprisingly effective with its biggest drawback being that the hands are repositioned at least twice during each rotation of the tool. A worker could easily overcome this difficulty by choosing one of the company’s high-end, ratcheting models (the Gunn model or one of the Pratts). The ratcheting auger handles also made provision for a user finding himself in a situation with inadequate clearance for a full rotation. An arm needed only to be detached and screwed into an opening at the handle’s top to convert the tool into an oversized, ratcheting corner brace. The advent of the more sophisticated boring machines did not, as one might expect, sound a death knell for the traditional T-auger. The T-auger’s easy portability, its flexibility in a variety of work situations, and its modest cost were factors ensuring continuing popularity. Pratt’s auger handle no. 4 was considered the top of the line and cost dealers a mere $24.00 per dozen. The cheapest model, the non-ratcheting Pratt, cost fifty cents each if purchased in similar quantities.

Illustration credits

- Factory view: Picturesque Franklin County. Northampton, Mass.: Wade, Warner & Company, 1891.

- Power hacksaw: Catalogue No. 35. Millers Falls, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1915.

- Pratt’s auger: Catalogue No. 25. New York: Millers Falls Co., [ca. 1897].

References

- On Pratt’s contribution and the Columbia exposition: Allan D. Adie. “75 years of Honest Endeavor.” Dyno-mite, December 1943, p. 19.

- McCoy’s self-opening brace jaws were awarded United States Letters Patent No. 421,420; his three-jaw drill chuck, no. 568,539; his angular bit stock, no. 586,053.

- The Rogers auger handle was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 484,050. Pratt’s ratcheting auger handle: United States Letters Patent No. 438,860.