Henry L. Pratt

The president of the Millers Falls Company for thirty-two years, Henry Lee Pratt was born in Shutesbury, Franklin County, Massachusetts, on July 14, 1826. He was the fifth of the eight children of Ephraim Pratt and Huldah Pierce. His father, a church deacon, was a farmer of modest means who supplemented his income by teaching country school and taking surveying jobs as they became available. Ephraim Pratt’s sons were promising students. Three of the boys, Hiram Alden, Henry Lee, and Lemuel Church, became public school teachers, and a fourth, Ephraim Lorrison, became an inventor.(1)

Dissatisfied with the dismal financial prospects facing a nineteenth-century schoolteacher, Henry Pratt soon opted for a life in business. He left New England and relocated to Cleveland, Ohio, where he became involved in a business that manufactured wooden chairs. The situation did not suit him. Pratt returned to his native Franklin County in 1859 and started a lumber business. In 1863 he bought the local poor farm from the Town of Wendell with an eye to rehabilitating an abandoned mill site on the property.(2) A ad appearing in the Greenfield Gazette and Courier on October 10, 1863, indicates the mill building itself must have been beyond repair.

Man Wanted — I will give any man who understands running a sawmill a valuable mill privilege, with dam built, canal dug and timber for the mill frame on the ground, and will also loan money to finish the mill and take my pay in sawing as the usual rates. There is timber enough within one mile of the mill to keep it stocked for many years. Location ten miles from Greenfield and three miles from the railroad. — H. L. Pratt

The advertisement makes it clear that Pratt was more interested in selling lumber than in sawing it. He found a taker in a man named Haskell who agreed to his terms, built a sawmill, repaired the dam, and promptly defaulted. In 1864, Henry Pratt sold the site to Amos Morrill and the Haywood brothers. Two years later, he sold the remainder of his lumber business and left Franklin County to become a principal in a Michigan-based based business, the Detroit Chair Company.(3) Pratt advertised the sale of his lumber enterprise in the Greenfield Gazette and Courier on April 30, 1866.

Timber Land. — Being about to change my business I offer for sale 100 acres of land, heavily timbered, for twenty dollars an acre. The land is twelve miles east of Greenfield, five miles from Grouts Corner and three miles from North Leverett. To the purchaser I will give all my sleds, wagons, yokes, chains, hooks, saws, &c. with the benefit of a lumber business seven years established. — H. L. Pratt

Millers Falls Mfg. formed

By May of 1868, Pratt was again back in Greenfield looking for investment opportunities. He soon teamed up with Levi J. Gunn, Charles H. Amidon, and James Moore to build a hardware factory and sawmill at the falls of the Millers River at Grouts Corner. The men incorporated the new business as the Millers Falls Mfg. Company, and Henry Pratt left the area soon afterward to establish a sales office in New York City. Pratt and his wife, the former Frances S. Stoughton, moved to Brooklyn’s upscale First Ward, an area now referred to as Brooklyn Heights. The couple’s location provided all the benefits of suburban living while providing easy access to the company offices at 87 Beekman Street (in Manhattan), a short ferry ride across the East River. Pratt was anything but homesick for Massachusetts. Over the next three decades, he would visit the plant just twice a year—combining one of his trips with the annual directors’ meeting.

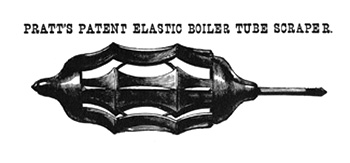

Henry Pratt became administrator of his brother Ephraim’s estate when the inventor passed away on February 19, 1867. Though Ephraim L. Pratt patented designs ranging from an apple parer and gun barrel scrapers to a flour sifter and a tobacco cutter, he managed to avoid the pitfalls of financial success and died a man of modest means. One of his designs, a boiler tube scraper protected by United States Letters Patent No. 66,387, was assigned to Henry Pratt fifteen months after Ephraim’s death. More rigid than the standard wire cleaning brush, the scraper was sold by the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company and proved to be effective in removing the toughest deposits from boiler flues. Produced in a variety of diameters, and priced at a dollar an inch, the Millers Falls Company marketed “Pratt’s Elastic Boiler-Tube Scraper” for the next thirty years.

Inventions

Though involved in the sales side of the business, Pratt played an active role in the development of the product line. During his years as president of the Millers Falls Company, Henry Pratt was awarded eight patents—five of them for saws. A highly intelligent man, the understanding of what were, after all, simple tools was not beyond him. A memoriam published after his death noted:

He himself possessed considerable inventive genius which took tangible form in his work at the bench in Manhattan and resulted in some desirable improvements that were embodied in the tools manufactured at the factory in Greenfield.(4)

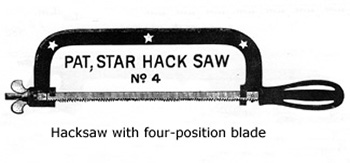

The company credited Pratt with the idea for the reciprocating arm that provided the back-and-forth sawing motion for the company’s highly successful power hacksaw.(5) Though the final product was a collaborative effort, Pratt’s idea provided the spark for the project, and the patent was registered in his name. His other saw patents appear to have been individual efforts. All were put into production and all sold well. Pratt designed the company’s wooden bracket saw frame and developed the blade-fastening mechanism that characterized its better spring steel bracket saws. He also designed a mechanism for holding hacksaw blades with a captive bent pin and went on to patent a hacksaw frame that allowed a blade to be positioned in any of four directions.

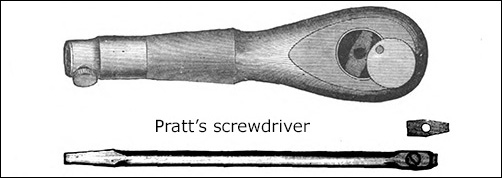

In 1884, notices appeared in the trade literature announcing Pratt's Multi-form screwdriver.(6) His invention featured a rosewood handle with a receptacle for storing small screwdriver points. The interchangeable points, held in place by a small screw, were not ground to a bevel allowing for a more accurate placement into the slot on the head of a target screw. A square-tanged bit fitted into an end socket allowed for the handle's use as a traditional screwdriver. If a screw proved stubborn, the bit could be placed into the handle at a right angle to allow for the application of more torque. In an extreme case, the square-tanged bit could be removed from the handle and fitted to a standard bit brace, harnessing that tool's ability to get the job done. One of his less successful inventions, Pratt's multi-form screwdriver was out of production by the early 1890s.

Two of Pratt’s non-saw patents were extremely successful. One protected the two-jaw chuck used on the company’s hand drills for two decades; a second covered a ratcheting T-auger that allowed a part of the handle to be re-positioned for drilling in tight spaces. A third non-saw patent, for a brace with a ring-type ratchet adjuster similar to those used on the company’s tools, does not appear to have been produced.

Plymouth church scandal

Soon after settling in Brooklyn, Pratt became a member of the fashionable Plymouth Church, a Congregational body whose pastor, Henry Ward Beecher, was considered the foremost preacher in the United States. Beecher, from one of New England’s most prominent families, was brother to the abolitionist novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe and the son of noted evangelist Lyman Beecher. When the pastor became caught up in one of the most notorious sex scandals of the nineteenth century, Henry L. Pratt, a prominent member of the church, found himself entangled in the fallout. Though historians still quibble about Beecher’s culpability, the evidence that the good minister involved himself in a series of dalliances with congregants of the fair sex is substantial. In 1865, Theodore Milton filed criminal charges against Beecher for alienating the affections of his wife. News of the alleged affair and subsequent trial took the country by storm, and the titillating details of the case played themselves out in newspapers from coast to coast.(7)

Tilton’s marriage was destroyed and his court case lost when his wife Elizabeth denied involvement with Beecher. The case had barely been put to rest when Henry C. Bowen, a founder of Plymouth Church and associate of Tilton, testified before a church council that, to his best knowledge, Beecher was “an adulterer, a perjurer and a blasphemer.” Bowen was convinced that Beecher had been involved with his wife as well but steadfastly refused to identify her as the object of the minister’s attentions. When angry church members brought charges against Bowen, Henry L. Pratt served as chair of the committee charged with investigating the matter. The Examining Committee met at Pratt’s house at 77 Hicks Street and eventually recommended that Bowen be excommunicated. At a special church meeting held to take action on the report, Pratt read the committee’s recommendation and in the ensuing discussion had the pleasure of hearing himself referred to as “merely a tool of Mr. Beecher.” The Examining Committee’s recommendation was adopted, and Henry C. Bowen was excommunicated from the church that he had helped to found.

Two years later, Henry Pratt was again drawn into the fray. Elizabeth Tilton, the woman who had denied having an affair with Henry Ward Beecher in 1875, instructed her legal representative to issue a notice to the press that she had misrepresented her relationship with Beecher and had, indeed, been intimate with him. The nation’s newspapers took up the story, and Plymouth church was once again involved in the scandal. When a member of the congregation brought a complaint against Mrs. Tilton, the Examining Committee was called upon to investigate the charges. The committee report—recommending excommunication—was presented at an annual business meeting of the church moderated by Henry Pratt. When the motion to strip Tilton of her membership was made, Pratt asked those in favor to show their hands. Fifteen or twenty members of the two hundred or so present signaled their approval. When the call for the opposed yielded not a single hand, Pratt ruled that the vote for excommunication was unanimous. Although the divisive scandal would eventually result in at least seven of the church’s most prominent members being excommunicated or dropped from its rolls, Henry Ward Beecher remained popular with his congregation.(8)

Final years

Although the Millers Falls Company relocated its Manhattan office several times, Henry and Frances Pratt remained steadfast in their commitment to their Brooklyn Heights neighborhood. Suburban life agreed with them, and Henry’s commute to the office was no doubt greatly simplified by the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883. Despite the Beecher scandals, Plymouth Church continued to play a large part in the couple’s life. Henry remained active in the congregation for thirty-two years, served as a deacon for most of that time, and instructed several generations of young women in the church’s Sunday School program. When the Pratts' house at 77 Hicks Street was razed as part of a Plymouth Church expansion project, the couple moved to 69 Orange Street, around the corner from the Hicks Street location and several doors from the church.

When Henry Pratt began to suffer from health problems in 1898, Edward P. Stoughton took over the active operation of the New York Office. Pratt died of heart failure on December 13, 1900. At the time of his death, Pratt's estimated net worth was $350,000—the equivalent of twelve million United States dollars in 2022.(9)

Patents

| Patent Number | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| D 8,381 | June 8, 1875 | design patent scroll saw frame |

| 177,659 | May 9, 1876 | scroll saw frame |

| 194,109 | January 3, 1877 | drill-chuck |

| 200,757 | February 26, 1878 | ratchet bit brace |

| 292,176 | January 22, 1884 | saw fastening and frame |

| 345,256 | July 6, 1886 | saw frame |

| 438,860 | October 21, 1890 | auger handle, assigned to Millers Falls Company |

| 502,996 | August 8, 1893 | hacksaw machine, assigned to Millers Falls Company |

Illustration credits

- Portrait: Hardware Dealers Magazine, v. 43, no. 253, January 1915.

- Boiler tube scraper: Catalogue 1887. New York: Millers Falls Company, 1887. (Reprint: Ken Roberts Pub. Co., 1981.)

- No. 4 hacksaw: Catalogue 1887. New York: Millers Falls Company, 1887. (Reprint: Ken Roberts Pub. Co., 1981.)

- Linked image of power hacksaw: Catalogue no. 35. Millers Falls, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1915.

- Multi-form screwdriver: Carpentry and Building, September 1884.

- Drawing of Plymouth Church: Abbot Lyman. Henry Ward Beecher: a Sketch of his Career... Hartford, Conn.: American Publishing Co., 1887, p. 221.

References

- Pratt family: Biographical Review: Sketches of the Leading Citizens of Franklin County, Massachusetts. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company, 1895. p. 532-535.

- The Wendell saw mill: “Supreme Court Decisions.” Gazette and Courier. Greenfield, Mass., Jan 14, 1867. (Pratt was sued.)

- H. L. Pratt is listed as treasurer of the Detroit Chair Factory in the Michigan State Gazetteer and Business Directory for 1867-8. Detroit: Chapman and Brother, 1867. p. 164.

- Pelletreau, William. A History of Long Island from its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time. Vol 3. New York : Lewis Publishing Company, 1905. p. 259

- Allan D. Adie. “75 Years of Honest Endeavor.” Dyno-mite, December 1943, p. 19.

- "Pratt's Multi-form Screw Driver." Carpentry and Building. September 1884, p. 174.

- Robert Shaplan. Free Love and Heavenly Sinners: the Story of the Great Henry Ward Beecher Scandal. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1954.

- Pratt’s role in the Beecher-Tilton scandal: The New York Times, March 9, 15, 29, 31; May 11, 19, 1876; June 14, 26, 1878.

- Obituaries: “Henry L. Pratt.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 13, 1900, p. 6; Proceedings at the Twenty-Second Annual Meeting and the Twenty-Second Annual Festival of the New England Society in the City of Brooklyn. Borough of Brooklyn, 1902, p. 12; Greenfield Recorder. December 19, 1900.