Millers Falls Company: 1920-1930

New company presidents

When Edward P. Stoughton became chairman of the Millers Falls Company’s board of directors in 1920, Kingman Brewster, a lawyer who had served as vice-president for Greenfield Tap & Die, replaced him as Company President. Brewster’s tenure at the Tap & Die works had not been a lengthy one. A fractious relationship with his new board of directors resulted in a stay just as brief. (He was active in the president’s role for less than a year.) Rogers family tradition has it that the incident triggering Brewster’s departure involved Chairman Stoughton’s displeasure at the purchase of a carload of golden oak furniture for the factory offices at Millers Falls. Stoughton, on one of his frequent trips to Europe, learned Brewster would be traveling to the continent and arranged for a meeting where he asked for Brewster’s resignation. The golden oak office furniture, anything but luxurious, remained at the plant in Millers Falls until its closure in the late 1960s.(1)

George Rogers’s son, Philip, assumed the responsibilities of company president in 1920. Philip Rogers had earned a degree in mechanical engineering at the Sheffield Scientific School, a semi-autonomous unit within Yale University. After his graduation in 1910, he began working for the Millers Falls Company, taking a position in the heat and dirt of the foundry core room. He soon became a machinist in the Automatic Screw Department and moved from there to the Tool Room, where he became head draftsman. In 1915, Philip Rogers was promoted to head of the firm’s Production Planning Department, a position he left in 1917, the year that the United States entered the Great European War. Rogers enlisted in the armed forces, served a two-year stint, and returned to the factory in 1919. Prior to ascending to the presidency, he served for a time as assistant plant superintendent. Philip Rogers’s term as president would be the longest in the company’s history, forty-two years.(2)

National Machine & West Haven Manufacturing Companies

In 1920, with an eye toward the burgeoning automobile repair market, the Millers Falls Company acquired the National Machine Company of Brattleboro,Vermont. The National Machine Company was a general-purpose machine shop managed by A.F. Roberts employing forty hands and manufacturing several well-designed automobile jacks. Although National Machine's primary business was centered on the production of car and truck jacks, its acquisition added such tools as rim wrenches and valve grinders to the Millers Falls product line as well. The Millers Falls Company did some initial work to improve the National Machine products but chose not to invest in the development of an extensive line of tools for the automotive mechanic. Employment at the former jack company averaged around thirty-five for most of the decade after its purchase, and although the Brattleboro plant was closed in 1931, Millers Falls catalogs continued to list automotive jacks through the Second World War. Kenneth H. Saunders, manager of the Brattleboro plant, moved to Millers Falls in 1930 and became part of the administrative team. In charge of production standards, payroll, and cost control for over thirty years—he eventually became the Millers Falls Company Treasurer.(3)

Millers Falls acquired a second firm in 1920—the West Haven Manufacturing Company, a business located at 22 Elm Street in West Haven, Connecticut. The purchase was precipitated by a decision by Clemson Brothers, of Middletown, New York, to terminate its long-standing agreement to supply hacksaw blades to Millers Falls. A younger generation of Clemson managers had concluded the company would be better off marketing the blades itself. Millers Falls was unprepared for the decision; as sole distributor, it was Clemson’s only outside customer, and it had been marketing Clemson blades under the Star trademark since 1883. The arrangement was so well-established that the companies had not signed a contract in years.(4)

West Haven Mfg. was a logical buyout target since the company had been producing hacksaws and blades under the popular Universal brand name since its incorporation by Charles E. Graham and Frank S. Bradley in 1902. Advertised as “the best hack saw on earth,” the firm’s blades were stamped with an easily recognized globe trademark, and consumer recognition of the brand was such that Millers Falls would continue to associate it with parts of its hacksaw line for the next three decades. As an added benefit, the takeover brought with it West Haven’s line of punches and nail sets. West Haven Manufacturing was a going concern. Depending on conditions, employment varied between 100 and 200, and at the time of its purchase by Millers Falls, the operation was manufacturing a million hacksaws a year.(5)

West Haven Manufacturing sold a line of belt-driven power hacksaw machines marketed under the Universal and Acme brand names. The 1918 West Haven catalog depicts two Universal models that would have been in direct competition with the power hacksaws the Millers Falls Company was putting out. Also pictured are four ruggedly built Acme machines intended for heavier use and for which there were no Millers Falls counterparts. It is not known if Millers Falls continued to offer the West Haven power hacksaws, but none of the machines appeared in Millers Falls catalogs after the buyout. In addition to its saw blades, nail sets and punches, West Haven’s Easy Grip hacksaw frames and machine-turned steel plumb bobs made the transition to the Millers Falls lineup.(6)

Millers Falls closed its West Haven branch in 1931. The machinery and the general manager, William H. Shortell, were moved to Greenfield. John Owen, president of Millers Falls in the early 1960s, would later remark, “The best thing to come out of West Haven was Bill Shortell.” Shortell became manager of the Millers Falls Company’s hacksaw operation and pioneered the use of molybdenum in the firm’s blades—creating the firm’s outstanding Blue-Mol product. The metallurgy in the Millers Falls Company’s highly profitable molybdenum, tungsten, and high-speed steel blades was second to none. William Shortell’s sons, Edward and Robert, would later join the company and contribute much to the operation. Edward Shortell would go on to become General Manager of the Millers Falls factories; Robert Shortell would make his mark in standards work.

The loss of the Clemson Star-brand blades necessitated a change in the Millers Falls Company trademark. The five-pointed star that had been, in one form or another, part of the company’s marketing efforts since the early 1880s was dropped. It was replaced by a small red triangle containing the words “Since 1868.” The new trademark, a joy to behold, would remain in use for the next forty years.(7)

The Accurate Level Company

The Millers Falls Company re-entered the wooden level business when it bought Lee Roy Connell's Detroit-based Accurate Level Company in 1926. Millers Falls had offered wooden levels until the end of the nineteenth century—selling Stratton Brothers Levels for most of the 1870s and 1880s, then marketing its own brand for several years around 1890 before offering the Stratton products again through most of the 1890s.(8)

The initial Millers Falls re-introduction, a modest one, appeared late in 1926 and consisted of three model numbers. By the time the company’s 1929 catalog was published, the firm had parlayed its investment into a line of levels that included thirty-nine model numbers in twelve distinct styles, with bodies manufactured of air-dried mahogany, air-dried white pine, or aluminum. Masons’ levels also made their appearance—a first for the company. There is no indication in Catalog No. 40 (1929) that Millers Falls had continued to operate the Accurate Level plant at Detroit.

Electric tools & hand planes

Millers Falls introduced electric tools to its product line the same year as the levels. The company was well on its way to abandoning the strategy of marketing dozens of variations on almost identical products. It pruned its line of braces and drills; additions to the lineup reflected a concern with adding new categories of tools. The about-face was necessary as a number of the manufacturer’s old standbys had become increasingly hard to sell. The development of electrical jig saws and lathes sounded the death knell for foot-powered hobbyist machinery. Boring machines were fast becoming obsolete due to changed techniques for building barns and bridges, and the competition from power tools. The company dropped the Goodell and Lanfair spokeshaves, and it would soon abandon its miter planer. Its power hacksaws had become antiquated; there was no longer a need to sell a half dozen hand-operated drill presses. The firm’s new electric tools, its new levels and a new line of hand planes represented carefully conceived strategy on the part of management.

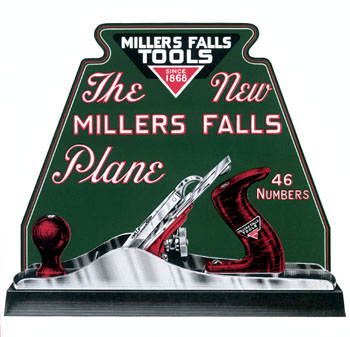

The company came to the manufacture of hand planes relatively late in the game. The introduction of the planes in 1928/29 was a large-scale, well-planned endeavor. Rather than introducing several planes and gradually expanding production, forty-six numbers—twenty-one of them block planes—were simultaneously brought to market. The planes were copies of existing Stanley production and of excellent quality. Castings for the beds were aged prior to machining; fit and finish were top-notch. The move was a bold one considering that the Stanley Works, having purchased most of its competition, thoroughly dominated the market for hand planes. It is a testimony to the quality of the Millers Falls products and the company’s skill in marketing that the new tools were a success. A great deal of thought had gone into the appearance of the planes, colorful sales displays, and visually pleasing promotional material. The bench planes, with their nickel-plated lever caps, red frogs, and rosewood totes, were stunning. Company executives must have been pleased with the results. A flashy, attention-grabbing appearance was to characterize the rollout of many of its products over the next several decades.

The bench planes were also promoted on the basis of their jointed lever caps. The standard lever cap used by competitors applied pressure to the chip breaker/cutter assembly at two points—one at the point of contact with the cap’s cam lever and the other along the lower edge of the cap where it made contact with the hump of the chip breaker. The hinged cap was designed to apply force to the chip breaker/cutter assembly at a third point, just above the chip breaker hump. Three points, rather than two—the company advertised the arrangement as a method for preventing chatter. The jointed lever cap was developed by Charles H. Fox, a Millers Falls employee who assigned the patent to the company.(9)

Mohawk Tools

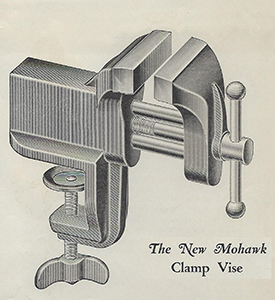

Millers Falls marked its sixtieth anniversary in 1928. Although official celebrations were modest, the company used the event to introduce a line of budget-priced tools to the hardware trade. A two-page, single-fold trade circular announced the rollout. The company's lukewarm attitude toward the new tools is evident from the almost apologetic announcement on the circular's introductory page. To wit:

These tools will not bear our name. They will be packed in plain boxes with end label marked "Mohawk." We do not intend to catalog these items and do not promise to manufacture them for a definite length of time. However, we will have a stock available for the remainder of this year at least.(10)

The five tools included a hacksaw frame, a hand drill, a one-speed breast drill, a polishing head, and a vise. Despite the inauspicious beginning, the lower-priced tools sold well enough to convince the company to add another eight tools to its economy line. Among others, the additions included a bit brace, a wooden and an aluminum level, an automatic drill, a ratcheting screwdriver, and a carving tool set.

Mohawk tools remained in production until 1931, three years after the rollout, when the Millers Falls Company incorporated them into a larger line of economy tools named Mohawk-Shelburne. The company discontinued the Mohawk-Shelburne line in 1948.

Illustration credits

- Factories: Catalog No. 40: January 1929. Millers Falls, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1929.

- Level: Wood and Aluminum Levels. Millers Falls, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., [undated brochure, ca. 1927].

- Plane display: Catalog No. 40: January 1929. Millers Falls, Mass. : Millers Falls Co., 1929.

- Mohawk vise: Announcing—5 "Mohawk" Tools. Millers Falls, Mass. : Millers Falls Co., [1928].

References

- Telephone interview, John J. Owen, Millers Falls Company president from 1962 to 1965, March 5, 2005. John Owen is the grandson of George E. Rogers and the nephew of Philip Rogers. Kingman Brewster’s son, Kingman Brewster, Jr., went on to become a highly regarded president of Yale University, and later, United States Ambassador to Great Britain.

- “Rogers Learned Business by First Hand Experience.” A Century of Experience: Millers Falls Company. Greenfield, Mass.: Greenfield Record, Gazette and Courier, August 13, 1968. unpaged.

- On the Brattleboro factory: L. A. Whitney. “History of Our Plant in Brattleboro, Vermont.” Brace Bits, v. 1, no. 4, February 1921, p. 1-2; On Kenneth Saunders: “This is His Story.” Dyno-mite, September/October 1955, p.12-13.

- On Clemson Brothers ending its relationship with Millers Falls: Telephone interview with John J. Owen, Millers Falls Company president from 1962 to 1965, March 5, 2005.

- On West Haven: Modern History of New Haven and East New Haven. New York: S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1918. p. 222-225; “The Drugan Story.” Dyno-mite, October 1957, p. 12-13; “Our New Plant in West Haven.” Brace Bits, v. 1, no. 2, December 1920, p. 1-2.

- The West Haven Manufacturing Company: Makers of “Universal” Hack Saw Blades ...: Catalog No. 15. West Haven, Conn.: West Haven Mfg., 1918.

- On William Shortell and changing the Millers Falls trademark: Telephone interview, John J. Owen. March 5, 2005.

- On the date of the Accurate Level acquisition: Pearl B. Care, Anastacia Burnett, and Doris A Felton. The History of Erving, Massachusetts, 1838-1998. Erving, Mass.: Erving Historical Society, 1988. p. 199. On Connell's ownership: Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office, v. 338, September 1925, p. 255.

- The Fox lever cap was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 1,822,520.

- Millers Falls Company. Announcing—5 "Mohawk" Tools. Millers Falls, Mass. : Millers Falls Company, [1928].