Charles H. Amidon

Amidon’s early years

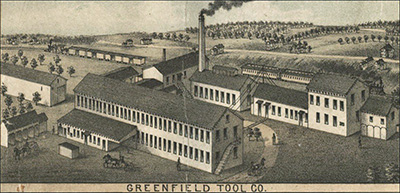

Charles Henry Amidon was the son of David Amidon, a shoemaker from Reedsboro, Vermont, who moved his family to Monroe, in Franklin County, Massachusetts, in the late 1820s. Charles, the third of nine children, was born there on the 28th of May in 1830. The Amidon family appears to have moved back and forth between Massachusetts and Vermont several times during Charles’ childhood—federal census records indicate alternating birthplaces for some of the younger children.(1) At the age of twenty-two, Charles Amidon married Louisa M. Yeomans, a young woman working as a servant in the nearby town of Ashfield. The couple moved to Greenfield where Charles took a job with the Greenfield Tool Company—an enterprise on its way to becoming one of the largest manufacturers of wooden hand planes in the United States. Their marriage was not a lengthy one; Louisa died at Greenfield in December 1854. Ten months later, Charles married again, to Harriet E. Rounds, the woman who became his lifelong companion.

Charles Henry Amidon was the son of David Amidon, a shoemaker from Reedsboro, Vermont, who moved his family to Monroe, in Franklin County, Massachusetts, in the late 1820s. Charles, the third of nine children, was born there on the 28th of May in 1830. The Amidon family appears to have moved back and forth between Massachusetts and Vermont several times during Charles’ childhood—federal census records indicate alternating birthplaces for some of the younger children.(1) At the age of twenty-two, Charles Amidon married Louisa M. Yeomans, a young woman working as a servant in the nearby town of Ashfield. The couple moved to Greenfield where Charles took a job with the Greenfield Tool Company—an enterprise on its way to becoming one of the largest manufacturers of wooden hand planes in the United States. Their marriage was not a lengthy one; Louisa died at Greenfield in December 1854. Ten months later, Charles married again, to Harriet E. Rounds, the woman who became his lifelong companion.

Amidon’s aptitude for things mechanical soon became apparent. Between 1852 and 1854, he was one of the five men at Greenfield Tool assigned the difficult task of making complex wooden plow planes.(2) He advanced to a position as a machinist and received his first exposure to the patent application process as co-assignee of a hollow mortising chisel he had developed with A. C. Hitchcock, Greenfield’s filletster plane specialist.(3) While at the Tool Company, Amidon made the acquaintance of Levi Gunn, his future partner and an eventual co-founder of the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company. The two men worked well together and soon held the contract for the manufacture of all the Greenfield Tool Company’s tools.

In 1861, Charles Amidon left the Greenfield Tool Company and associated with Levi Gunn for the purpose of building wash wringers. Amidon became a full partner in the operation two and one-half years later. A history of their business, their involvement with William H. Barber's ground-breaking bit brace and Amidon's highly successful adaptation of that design can be found on the Gunn & Amidon page of this website. In 1868, the two men joined with Henry L. Pratt and other investors to form a much larger enterprise for the manufacture of lumber, bit braces, and hand tools. The story of the founding of this company and Amidon's subsequent departure (in 1870) is recounted on the author's Millers Falls Manufacturing Company page.

Amidon Manufacturing Company

Amidon’s departure from the company left him with cash in his pocket.(4) In January 1870, the month he left the operation, Amidon bought a farm from Solomon Caswell, and two weeks later, he purchased a water-power right on the Millers Falls Mfg. Company’s canal. The summer found him occupied with building a new barn (with a full cellar) on his farm and a factory at the canal site. The new, two-story brick factory was completed in January 1871. The building was to be given over to the production of baby carriages, and Charles Amidon was not alone in assuming the risks of the venture. Charles E. Fisk, a Greenfield coach maker who had once shared a house with Amidon, became a partner in the operation. Orson F. Swift, a flighty investor and dealer in tinware, joined the firm soon after, and Henry M. Dunbar, a longtime acquaintance of Amidon, became an investor before the year was up. The new business was named the Amidon Manufacturing Company.

Amidon’s departure from the company left him with cash in his pocket.(4) In January 1870, the month he left the operation, Amidon bought a farm from Solomon Caswell, and two weeks later, he purchased a water-power right on the Millers Falls Mfg. Company’s canal. The summer found him occupied with building a new barn (with a full cellar) on his farm and a factory at the canal site. The new, two-story brick factory was completed in January 1871. The building was to be given over to the production of baby carriages, and Charles Amidon was not alone in assuming the risks of the venture. Charles E. Fisk, a Greenfield coach maker who had once shared a house with Amidon, became a partner in the operation. Orson F. Swift, a flighty investor and dealer in tinware, joined the firm soon after, and Henry M. Dunbar, a longtime acquaintance of Amidon, became an investor before the year was up. The new business was named the Amidon Manufacturing Company.

Amidon had known Henry Dunbar since his youth. Henry was the son of Charles Dunbar, one of the Connecticut Dunbars who had migrated to the Monroe area of Franklin County earlier in the century. Ties between the Dunbars and Amidons were close; the families had shared a household in 1850. Charles Amidon’s mother, Bertha, was a Connecticut Dunbar, and it is likely he and Henry were cousins. Henry had worked for Charles Amidon during the early years of the Millers Falls Mfg. Company and lost four hundred dollars in stock and tools when fire destroyed the factory in December 1868.

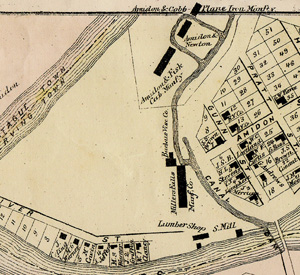

The Amidon Manufacturing Company was located next to the factory of Solomon H. Amidon, Charles’ younger brother. Solomon and his partner, Jesse Newton, built a two-story, 40 x 60-foot brick building to serve as headquarters and manufactory for Amidon & Newton, producers of small hardware items and operators of a successful construction company. On March 26, 1872, Solomon Amidon was issued United States Letters Patent No. 124,999 for a stay brace for trunk lids, and while it is not known if the design was ever produced, it is indicative of the sort hardware the partners manufactured. After a short stint in manufacturing, Solomon Amidon became a building contractor. By 1895, he had built the bulk of the structures in the village of Millers Falls: 140 houses, several churches, factories, a dam, and what was referred to at the time as a block—a large structure that incorporated business and residential units.(5)

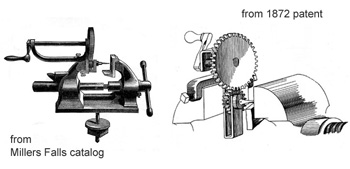

Charles Amidon’s responsibilities at the carriage shop did not put an end to his design work. He soon became involved in the development of drilling and boring devices equipped with feed mechanisms. In December 1872, he patented a hand drill with an offset crank that could be clamped to one jaw of an ordinary mechanic’s vise. The drawings accompanying the patent bear a marked resemblance to a vise drill pictured in a ca. 1874 Millers Falls Company catalog. A side-by-side comparison of the illustrations (at left) shows similarities in the gearing and general thinking behind the tools but a different approach to the design of the crank. Since the text accompanying the catalog illustration makes no mention of Amidon and contains no patent information, there is not enough evidence as yet to conclude that the tool sold by Millers Falls was designed by him. On July 1, 1873, Charles Amidon patented a bit brace that could be converted into a hand drill. The tool was designed to be mounted on a frame equipped with a feed device that would move a piece of stock into a rotating drill bit. Although the feed mechanism was not successful, a bit brace based on the 1873 patent was put into production—a move that did much to enhance the diversity of the Amidon Manufacturing Company’s line of tools.(6)

Charles Amidon’s responsibilities at the carriage shop did not put an end to his design work. He soon became involved in the development of drilling and boring devices equipped with feed mechanisms. In December 1872, he patented a hand drill with an offset crank that could be clamped to one jaw of an ordinary mechanic’s vise. The drawings accompanying the patent bear a marked resemblance to a vise drill pictured in a ca. 1874 Millers Falls Company catalog. A side-by-side comparison of the illustrations (at left) shows similarities in the gearing and general thinking behind the tools but a different approach to the design of the crank. Since the text accompanying the catalog illustration makes no mention of Amidon and contains no patent information, there is not enough evidence as yet to conclude that the tool sold by Millers Falls was designed by him. On July 1, 1873, Charles Amidon patented a bit brace that could be converted into a hand drill. The tool was designed to be mounted on a frame equipped with a feed device that would move a piece of stock into a rotating drill bit. Although the feed mechanism was not successful, a bit brace based on the 1873 patent was put into production—a move that did much to enhance the diversity of the Amidon Manufacturing Company’s line of tools.(6)

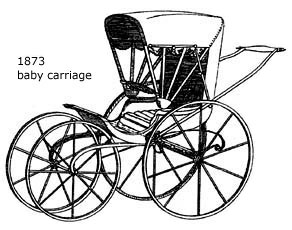

In January 1873, Charles H. Amidon was issued yet another patent, this one for a baby carriage with an adjustable push handle, pivoting rear wheels, and a recliner seat. Another baby coach patent followed in early 1875. It featured a bi-directional, adjustable top that allowed a surprising amount of flexibility in protecting a child from the sun. Modeled on the carriages of the well-to-do, the firm’s coaches were intended to appeal to a prosperous middle class, and it is not surprising that skilled carriage makers such as Charles Fisk were involved in their production.(7)

Unfortunately, the business climate in the mid-1870s was less than ideal—especially for companies whose well-being depended on discretionary spending by younger, middle-class consumers. Although the Amidon Manufacturing Company had begun to fabricate bit braces and other small items, its primary product—a high-end baby carriage—was highly vulnerable to an economic recession. A downturn, which began with the Panic of 1873, lasted for nearly four years, and Amidon Manufacturing, like so many other small companies, would struggle and fail.

Unfortunately, the business climate in the mid-1870s was less than ideal—especially for companies whose well-being depended on discretionary spending by younger, middle-class consumers. Although the Amidon Manufacturing Company had begun to fabricate bit braces and other small items, its primary product—a high-end baby carriage—was highly vulnerable to an economic recession. A downturn, which began with the Panic of 1873, lasted for nearly four years, and Amidon Manufacturing, like so many other small companies, would struggle and fail.

By February 1875, losses had reached the point at which it was necessary to declare bankruptcy. Although the factory and grounds were sold to satisfy creditors that June, the equipment remained in the hands of the principals, who continued to operate the business in the original building—now owned by the private bankers Cheney & Waite. (At some point, the firm, or at least some part of it, had been renamed the Amidon Bit Brace Company.)

The situation at Charles Amidon’s company went from bad to worse. On the evening of January 19, 1876, a fire broke out in the north attic of the operation’s factory. The ensuing conflagration destroyed two-thirds of the 123 x 50-foot building. The part of the structure that burned housed the carriage-making operation, and although the building belonged to Cheney & Waite the loss in tools and stock, was substantial. The enterprise was uninsured, and by the standards of the time, the $18,000 loss was substantial.(8) Enough of the factory remained, however, so that after a brief pause, the bit brace business was able to continue in the undamaged part of the building.

Charles H. Amidon and Henry M. Dunbar filed for personal bankruptcy within days of the fire. Seven months later, a notice that Charles E. Fisk had opened a carriage-making shop in Greenfield appeared in the Gazette and Courier. The manufacture of bit braces continued at the Amidon Bit Brace Company for a time, but in May of 1877, the equipment was sold to Elijah R. Saxton of Buffalo, New York.

Elijah Saxton and Amidon

Elijah Root Saxton had been a partner in Gunn & Amidon for a brief period in 1864 and 1865—a time when the business was known as Gunn, Amidon & Saxton. Saxton did well after his departure from the operation, relocating to Buffalo, New York, and becoming a partner in the Buffalo Forge Company, a steam forge originally founded by Henry Childs in 1863 which specialized in the manufacture of heavy-duty shafting and axles for rail cars.(9) Interested in the workings of his new hometown, E. R. Saxton became active in Republican Party politics and was elected alderman for Buffalo’s Second Ward. His decision to purchase the equipment of the Amidon Bit Brace Company factory was made with an eye to setting up an operation in Buffalo for the manufacture of small items for the hardware trade. The Greenfield newspaper reported that Saxton intended to manage the operation himself and to take on “an experienced mechanic from the East to oversee the workmen.” The article made no mention of a role for Charles Amidon.(10)

Elijah Root Saxton had been a partner in Gunn & Amidon for a brief period in 1864 and 1865—a time when the business was known as Gunn, Amidon & Saxton. Saxton did well after his departure from the operation, relocating to Buffalo, New York, and becoming a partner in the Buffalo Forge Company, a steam forge originally founded by Henry Childs in 1863 which specialized in the manufacture of heavy-duty shafting and axles for rail cars.(9) Interested in the workings of his new hometown, E. R. Saxton became active in Republican Party politics and was elected alderman for Buffalo’s Second Ward. His decision to purchase the equipment of the Amidon Bit Brace Company factory was made with an eye to setting up an operation in Buffalo for the manufacture of small items for the hardware trade. The Greenfield newspaper reported that Saxton intended to manage the operation himself and to take on “an experienced mechanic from the East to oversee the workmen.” The article made no mention of a role for Charles Amidon.(10)

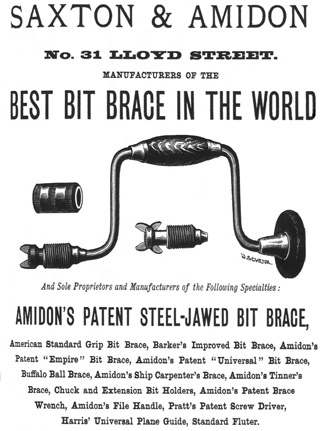

Two months after the sale, Charles Amidon assigned half of his patent for a brace wrench to Elijah Saxton, and on March 19, 1878, he assigned Saxton half interest in a thumb screw bit brace he had developed.(11) The men became partners and set up shop in Buffalo at 31 Lloyd Street. It is not unreasonable to suppose that the interest in the patents formed a substantial part of the bankrupt Amidon’s buy-in. The relative strength of the men’s positions in the firm is evidenced by the name of the enterprise—Saxton & Amidon, rather than Amidon & Saxton. The business offered braces based on Amidon's 1873 patent, marketed his thumb screw bit brace as the Universal Brace, and offered the brace wrench under the designation Amidon's Patent.

Although Charles Amidon lost the rights to his Barber Improved Brace when he left the Millers Falls Company, nineteenth-century attitudes toward deliberately confusing advertising were fairly relaxed. Saxton & Amidon felt little compunction in marketing a product with the misleading name Barker Improved Brace. The product's name traveled with Amidon when his partnership with Saxton folded, and there is no indication that any of the businesses were enjoined from using the name. Advertisements in the 1878 and 1879 Buffalo city directories indicate the partnership marketed boring tools identified as the American Standard Grip Bit Brace, the Empire Bit Brace, the Buffalo Ball Brace, Amidon's Ship's Carpenter's Brace, and Amidon's Tinners Brace. The lineup also included Pratt's patented screwdriver and the table-mounted jointer gauges and farm trucks patented by Milo Harris of Jamestown, New York.(12)

Saxton & Amidon maintained a sideline of selling lignum vitae and rosewood lumber by the ton, a quantity unimaginable to modern woodworkers, but perhaps the oddest of its merchandise were tools most suited to use by the woman of the house. The partners manufactured fluting irons, devices that, when heated, were used to press curves into the ruffles of milady's collars and cuffs. Sales must have been brisk for the company added an even more esoteric gadget that embossed decorative patterns, such as flowers or birds, into fabric. Patented by John Steinlein of Egg Harbor City, New Jersey, on February 1, 1876, the hand-operated embosser was "used for ornamenting under or other garments after they have been laundried" by passing them through a pair of heated rollers.

On April 20, 1880, Amidon was issued United States Letters Patent No. 226,646 for a chuck featuring a pair of short, springless jaws that were designed to be “simple, cheap and durable.” The 1880 chuck, inexpensive to manufacture and elegant in its simplicity, would remain in production until the mid-1890s. An 1883 ratchet brace that used a single disk-type pawl to control the direction of the tool’s rotation was not as successful. (Comparatively few have survived.)

Amidon’s partnership with Saxton lasted five years. In 1883, the business was declared insolvent. The Honorable James Sheldon appointed a receiver to sell the partnership's property at auction. A buyer for Elijah R. Saxton purchased the assets of the business for $24,500 in cash. The portion of the proceeds that went to Charles Amidon remains unknown, but when the dust had cleared, he emerged from the situation with the rights to his post-Millers Falls brace patents intact.(13)

Amidon & White

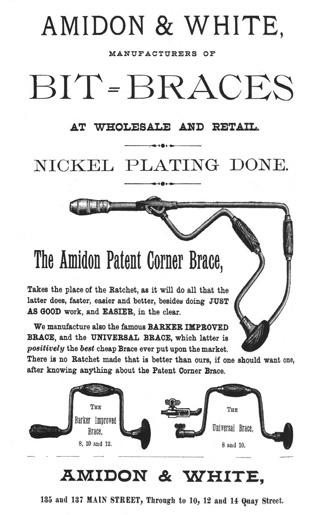

The details of the breakup with Amidon & Saxton had yet to be finalized when Charles Amidon partnered with former banker Ansley D. White to set up a factory in October of 1883. Located at 135 Main Street in Buffalo, the Amidon & White shop occupied two floors of a building whose footprint measured thirty-five by 150 square feet. The operation employed forty to fifty workers who collectively earned anywhere from $300 to $350 each week and who manufactured $100,000 worth of goods a year.(14) Since Amidon had retained the rights to his post-1877 braces, the operation sold a spring-loaded variation of his 1878 Universal Brace and a series of braces featuring Amidon's 1880 chuck.

In 1884, Amidon developed and patented a corner brace that would set the standard for the appearance of this type of tool. The basic design of the tool—an L-shaped frame with an angled crank resembling a standard bit brace—became the predominant pattern for most of the corner braces manufactured for the next century. It was described as “being indispensable to carpenters, bell-hangers and plumbers” and “the only practical tool for boring in corners and close to walls.” Far less successful was the odd-looking, globe jaw chuck Amidon designed later that year. Featuring oversized wing-type jaws with hemispherical inserts, the tool was clumsy, difficult to adjust, and expensive to manufacture. Much was made of its ability to handle bits in a variety of shapes and tapers, but the tool never caught on.

In 1884, Amidon developed and patented a corner brace that would set the standard for the appearance of this type of tool. The basic design of the tool—an L-shaped frame with an angled crank resembling a standard bit brace—became the predominant pattern for most of the corner braces manufactured for the next century. It was described as “being indispensable to carpenters, bell-hangers and plumbers” and “the only practical tool for boring in corners and close to walls.” Far less successful was the odd-looking, globe jaw chuck Amidon designed later that year. Featuring oversized wing-type jaws with hemispherical inserts, the tool was clumsy, difficult to adjust, and expensive to manufacture. Much was made of its ability to handle bits in a variety of shapes and tapers, but the tool never caught on.

Amidon & White also manufactured and sold a ratchet brace referred to as The Eclipse and an assortment of lathe chucks. The partners maintained a sideline in gold, silver, nickel, and copper plating and were not shy about promoting their services. An oddly written advertisement for their plating services appeared in the November 26, 1884, Buffalo Courier. Written in verse, it is reminiscent of an ode to the Amidon wash wringer published in the July 31, 1865, Greenfield Gazette and Courier. The ad in the Buffalo Courier carried the following verses under an illustration of the Amidon corner brace:

ACROSTIC

Nickle, Gold and Silver, Copper plating too,

In the best of style will A. & W. do.

Cold and damp November all Iron work impairs,

Kindly we invite you to seek their fine repairs.

Let none forget stove ornaments nickle plated well,

Each one that has tried them says "none can them excell."

Plating that is perfect long remains a beauty,

Learned they have that fact, and do their bounden duty.

All men in Erie county, who wish to please their wives

This business should call upon and bring their spoons and knives.

Improved in all respects, the methods that they use,

None trying once, their science will refuse.

Go where you will, this place is ever right,

P. S.—And thorough metal platers you'll find are

AMIDON & WHITE,

Amidon & Bastedo; Amidon Tool Corporation

When Amidon and White parted company in 1887, Ansley White moved on to become one of the principals of the short-lived American Bit Brace Company (1887-1892). Charles Amidon went into business with Walter Bastedo at 1451 Niagara Street (Amidon & Bastedo (1887-1890). Amidon & Bastedo continued offering the Eclipse model, the Barker Improved Brace, Amidon’s corner brace, and braces featuring the 1880 patented chuck. In 1888 the partners introduced a brace with a chuck based on Amidon's orginal Barber Improved design. They referred to the tool as Amidon's 2nd Improved Barber brace. The reworked chuck featured jaws held in place by means of a pin driven through its socket. The design was not patented and appeared on standard, ratcheting, and corner braces.

Bastedo moved on in 1890, and entries in local directories indicate that Amidon operated the business at Niagara Street without a named partner until 1894. At that time, he affiliated with Charles Dumont to form the Amidon Tool Corporation. Located at the Niagara Street address, Amidon Tool employed twenty-five hands, a number that included five shop boys under the age of sixteen.(15) Although it continued to be listed in various business directories as late as 1901, the Amidon Tool Corporation was formally dissolved in 1898. The primary focus of these later businesses involved the fabrication of bit braces, but other products were offered as well. Amidon & Bastedo is on record as providing nickel plating services; Amidon Tool Corporation also manufactured hacksaw frames.

The demise of the Amidon Tool Corporation lead to the personal bankruptcy of Charles H. Amidon in 1899. Had he remained with the Millers Falls Mfg. Company, he would have become a wealthy man. It is ironic that the success of the Millers Falls firm was in large part due to the solid foundation provided by the enormous sales of braces featuring Amidon's Barber Improved Chuck. A solid mechanic with at least twenty-two patents to his name, Amidon lacked the temperament to manage a business or remain in a partnership for any length of time. He may have been well aware of his shortcomings as a businessman. When asked his occupation by a federal census taker in 1880, Charles Amidon replied with the word “inventor.” He died sometime after 1900.

In 1900, a patent for a tire pump was issued to an individual named Charles H. Amidon who resided in Buffalo, New York. The pump is unlike any of the other Amidon designs and may be the work of the other Charles H. Amidon living in the city at the time—a younger man who also worked as a machinist. Charles H. Amidon and Harriet Rounds parented at least one child. Their son, Charles W. Amidon, was born in Millers Falls in 1872 and died in 1923. He is buried in Forest Hill Cemetery, Fredonia, New York.

Amidon's Patents

| Patent Number | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14,454 | March 18, 1856 | co-patentee, with A. C. Hitchcock, of wood chisel |

| 36,761 | October 28, 1862 | wringing machine |

| 47,079 | April 4, 1865 | improved wringing machine |

| 50,214 | October 3, 1865 | bit stock |

| 64,931 | May 21, 1867 | bit brace |

| 64,932 | May 21, 1867 | clothes wringer |

| 73,279 | January 14, 1868 | bit stock |

| Reissue 4,199 | December 13, 1870 | assignee, with L. J. Gunn, of A. C. Moore bit stock patent no. 16,931 |

| 134,237 | December 24, 1872 | improvement in drills |

| 134,623 | January 7, 1873 | baby carriage |

| 140,451 | July 1, 1873 | drill and bit stock |

| 161,086 | March 23, 1875 | child’s carriage |

| 193,632 | July 31, 1877 | brace wrench, assigned 1/2 interest to Elijah R. Saxton. |

| 201,379 | March 19, 1878 | bit brace, assigned 1/2 interest to Elijah R. Saxton. |

| 210,075 | November 19, 1878 | bit brace |

| 217,672 | July 22, 1879 | bit brace |

| 226,646 | April 20, 1880 | bit brace |

| 263,455 | August 29, 1882 | bit stock |

| 283,844 | August 28, 1883 | bit stock |

| 298,542 | May 13, 1884 | corner bit brace |

| 305,263 | September 16, 1884 | chuck |

| 348,182 | August 31, 1886 | machine to install heads on bit braces |

| 641,253 | January 16, 1900 | tire pump—possibly designed by another Charles H. Amidon living in Buffalo at the time |

Illustration credits

- Greenfield Tool factory: View of Greenfield, Mass. Boston: O. H. Bailey & Co., 1877.

- Map: F. W. Beers and G. P. Sanford. Atlas of Franklin Co., Massachusetts: from Actual Surveys. New York: F. W. Beers & Co., 1871.

- Baby carriage: United States Letters Patent No. 134,623.

- Linked drawing of stay brace for trunk lids: United States Letters Patent No. 124,999.

- Vise drill comparison drawings: ca. 1874 Millers Falls catalog and United States Letters Patent No. 134,237 (edited, copyright by author)

- Saxton & Amidon advertisement: Buffalo City Directory for the Year 1878. Buffalo: The Courier Company, 1878. p. 197.

- Amidon & White advertisement: Buffalo City Directory for the Year 1884. Buffalo: The Courier Company, 1884. p. 210.

References

- The reader should be advised that census records are inconsistent with regard to Charles H. Amidon’s birthplace.

- Donald & Anne Wing. “The Workings of a Plane Factory.” The Mechanick’s Workbench. No. 10, August 1980, p. 3, 10-11.

- United States Letters Patent No. 14,454.

- Unless otherwise cited, most information on the Amidon manufacturing company is courtesy of Gazette and Courier. Greenfield, Mass., Jan. 1870-May 1877.

- Biographical Review: Sketches of the Leading Citizens of Franklin County, Massachusetts. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company, 1895. p. 168.

- The drill: United States Letters Patent No. 134,237. The bit brace: United States Letters Patent No. 140,451.

- The pivoting wheel baby carriage: United States Letters Patent No. 134,623. The adjustable-top baby carriage: United States Letters Patent No. 161,086.

- Insurance and loss: "Franklin County." Massachusetts Spy. January 28, 1879. p.3

- The Industries of Buffalo: a Resumé of the Mercantile and Manufacturing Progress of the Queen of the Lakes ... Buffalo: Elstner Publishing Company, 1887. p. 258; Buffalo City Directory for the Year 1873. Buffalo: Warren, Johnson & Co., 1873. p. 161.

- 'Millers Falls." Gazette and Courier. Greenfield, Mass., May 21, 1877.

- The brace wrench: United States Letters Patent No. 193,632; the brace: United States Letters Patent No. 201,379.

- Buffalo City Directory for the Year 1878. Buffalo: The Courier Company, 1878. p. 197; Buffalo City Directory for the Year 1879. Buffalo: The Courier Company, 1879. p. 212. The Harris patents: United States Letters Patent No. 184,241; United States Letters Patent No. 215,918.

- "Brevities." The Buffalo Commercial Advertiser (Buffalo, New York). December 12, 1883. p. 3.

- The Industries of Buffalo. p. 112-113; Buffalo City Directory for the Year 1884. Buffalo: Buffalo Courier Co., 1884. p. 210.

- Eighth Annual Report of the Factory Inspector of the State of New York. Albany: James B. Lyon, 1894. p. 636.