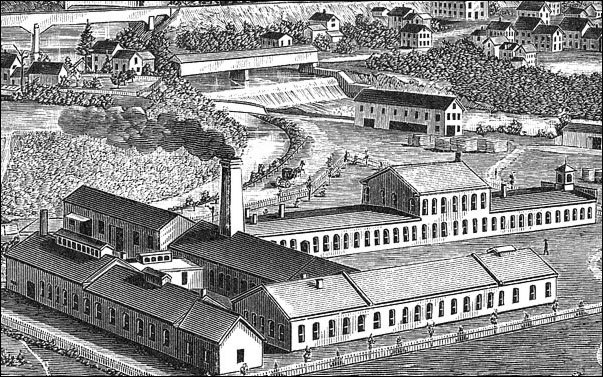

Millers Falls plant in 1879

A view of the plant

This bird’s eye view of the Millers Falls plant is taken from an 1879 book titled The History of the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts. It is rich in the amount of detail that rewards the careful observer. The plant is nearly double the size of that shown in an 1873 view presented earlier in this narrative. A second floor has been added to part of the main building; substantial additions have been added to the rear; and the wing which parallels the main building has doubled in length. A cupola, retained through several remodelings, has been added to the front of the main building, and several storage sheds have been built along the river. The mill dam can be seen in the background, and immediately upstream is a covered bridge that was built in 1872 and connected Bridge Street to Gunn Street. Behind the covered bridge is the railway bed that enabled the efficient transport of material and finished product from the plant’s remote location. (The village of Millers Falls was a station on the Vermont & Massachusetts and the New London railroads.) The company’s canal can be seen running from the dam to the plant. Directly behind it, and to the left, is the flat-topped hill that was home to Amidon, Gunn, and Pratt Streets.

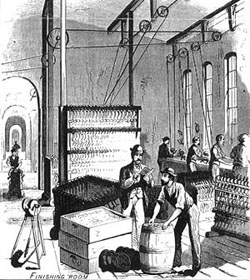

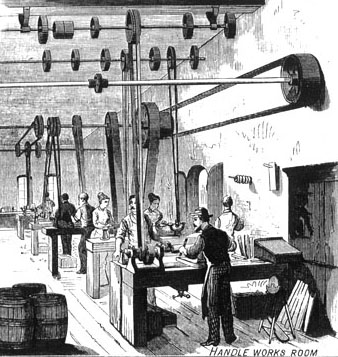

Several interior views of the Millers Falls plant were published on the cover of the popular journal Scientific American in the same year the bird’s eye view appeared in the Connecticut Valley book. Together with a few paragraphs of text, they tell us much about conditions inside the factory. To the degree possible, the exterior walls of the high-ceilinged rooms were pierced for windows to take advantage of natural light. An overhead system of belts and pulleys provided power to the grinders, lathes, drill presses, and milling machines used in manufacturing, and the company’s turbines could deliver up to three hundred horsepower to the network. Wooden floors were the norm, and the storage and use of solvents along with frequent sparks from the machines meant that fire was always a danger. The conflagrations experienced by the firm in its earliest years must have weighed heavily on the minds of its officers during construction planning as the main building was divided into six sections, each separated from the others by a heavy brick wall. A central corridor ran the length of the building and the doors dividing the sections were made of heavy iron and could be closed to prevent a fire from spreading. The series of arched doorways comprising the central corridor can be seen in the view of the finishing room at right. A close examination of the tools pictured shows braces, breast drills, wheels for treadle saws, and a foot-powered grinder.

Several interior views of the Millers Falls plant were published on the cover of the popular journal Scientific American in the same year the bird’s eye view appeared in the Connecticut Valley book. Together with a few paragraphs of text, they tell us much about conditions inside the factory. To the degree possible, the exterior walls of the high-ceilinged rooms were pierced for windows to take advantage of natural light. An overhead system of belts and pulleys provided power to the grinders, lathes, drill presses, and milling machines used in manufacturing, and the company’s turbines could deliver up to three hundred horsepower to the network. Wooden floors were the norm, and the storage and use of solvents along with frequent sparks from the machines meant that fire was always a danger. The conflagrations experienced by the firm in its earliest years must have weighed heavily on the minds of its officers during construction planning as the main building was divided into six sections, each separated from the others by a heavy brick wall. A central corridor ran the length of the building and the doors dividing the sections were made of heavy iron and could be closed to prevent a fire from spreading. The series of arched doorways comprising the central corridor can be seen in the view of the finishing room at right. A close examination of the tools pictured shows braces, breast drills, wheels for treadle saws, and a foot-powered grinder.

The Millers Falls Company employed 150 souls at the time of the article. To have referred to them as men would have been a misstatement. As can be seen in the illustration at right, women began to take up positions in the plant early on, although they were doing what was considered light work. The two women are seen putting the final touches on turned wooden handles—most likely using a scraper or sandpaper. Just behind them can be seen an arched doorway with its fireproof iron doors. Since the ceiling in this room is flat—it is most likely on the ground floor in that part of the plant to which an upper story had been added. The officers of the Millers Falls Company did everything they could to make the plant as self-contained as possible. The works included an iron foundry, a brass foundry, blacksmith shops, a tempering shop, a machine shop, pattern and wood turning shops, a grinding shop, and a polishing shop. There were also inspection rooms, stock rooms, offices, and of course, privies.

The Millers Falls Company employed 150 souls at the time of the article. To have referred to them as men would have been a misstatement. As can be seen in the illustration at right, women began to take up positions in the plant early on, although they were doing what was considered light work. The two women are seen putting the final touches on turned wooden handles—most likely using a scraper or sandpaper. Just behind them can be seen an arched doorway with its fireproof iron doors. Since the ceiling in this room is flat—it is most likely on the ground floor in that part of the plant to which an upper story had been added. The officers of the Millers Falls Company did everything they could to make the plant as self-contained as possible. The works included an iron foundry, a brass foundry, blacksmith shops, a tempering shop, a machine shop, pattern and wood turning shops, a grinding shop, and a polishing shop. There were also inspection rooms, stock rooms, offices, and of course, privies.

The Greenfield Gazette and Courier considered the Millers Falls Company to be “in the front rank of the women’s labor movement” and noted the women at its lathes proved themselves “equal to their more muscular brothers.” The manufacturer used large quantities of rosewood and lignum vitae in the production of the wooden parts of its hand tools. Rough logs were purchased in New York and shipped to the plant to be sawn into the small pieces needed for tool handles. The use of these exotic woods was an expensive proposition. Scrap was not discarded, but was transformed into such products as pen holders, knobs, and buttons. One especially productive young woman was reported to have turned out 10,000 such buttons in a single day.(1)

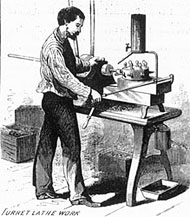

The latest technology

The company was proud of its machinery and did its best to keep abreast of current developments. The dapper worker in the illustration at left is pictured using a turret lathe. One of the uses to which the firm’s turret machines were put was the production of external shells for small universal chucks—products destined for eventual placement on hand drills, tool holders, or machinists’ lathes. A bar of iron would be put through the hollow mandrel of the lathe and turned, drilled, tapped, chamfered, finished, and cut off. The Millers Falls Company boasted a worker using such a machine could complete a chuck in five minutes. While, at first glance, the claim is accurate, it conveniently ignores the time and labor involved in manufacturing, assembling, and inserting the jaws—components necessary to make the shell functional. Be that as it may, the firm was proud of its capability for rapid and accurate production, touted it whenever possible and understood growth and survival depended on the ability to remain

competitive.

The company was proud of its machinery and did its best to keep abreast of current developments. The dapper worker in the illustration at left is pictured using a turret lathe. One of the uses to which the firm’s turret machines were put was the production of external shells for small universal chucks—products destined for eventual placement on hand drills, tool holders, or machinists’ lathes. A bar of iron would be put through the hollow mandrel of the lathe and turned, drilled, tapped, chamfered, finished, and cut off. The Millers Falls Company boasted a worker using such a machine could complete a chuck in five minutes. While, at first glance, the claim is accurate, it conveniently ignores the time and labor involved in manufacturing, assembling, and inserting the jaws—components necessary to make the shell functional. Be that as it may, the firm was proud of its capability for rapid and accurate production, touted it whenever possible and understood growth and survival depended on the ability to remain

competitive.

It is tempting to romanticize the company’s nineteenth-century history in terms of Amidon’s overshot waterwheel and a handful of workers turning out eighteen braces a day, but the story of the Millers Falls Company is one of shrewd investment, innovative products, aggressive marketing, and the use of cutting edge technology.

Illustration credits

- Birds-eye view of plant: History of the Connecticut River Valley in Massachusetts with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Philadelphia: L. H. Everts, 1879.

- Internal views of plant: Scientific American, March 22, 1879.

- Linked drawing of plant in 1873: Catalogue No. 35. Millers Falls, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1915.

References

- The information on the company’s use of tropical hardwoods and the role of women workers: “Millers Falls—Its Wonderful Growth and Promising Future” Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) November 4, 1872.