Millers Falls Company: 1880-1900

Clemson Brothers

In 1883, the Millers Falls Company entered into an agreement with Clemson Brothers of Middletown, New York, to become sole sales agent for Clemson's Star hacksaw blades. Clemson, founded in 1879 by George N. and Richard W. Clemson, was able to provide Millers Falls with metal-cutting blades of unmatched uniformity at astonishingly low cost. Millers Falls sold the blades as stand-alone items but lost no time in coming up with a series of hacksaw frames and marketing them under the Star brand.

At the time, the Millers Falls Company considered its main metal-sawing competitor to be the Stubbs saw, an English import with a significant problem. The Stubbs blades were pricey and dulled easily. Their cost was high enough to dictate they would be painstakingly and arduously re-filed rather than discarded when dull. By contrast, the Star blades were a metallurgical wonder. Although highly tempered and slow to dull, they were wondrously tough and resisted breaking. The Millers Fall Company did much to promote them, touting the fact that the new blades lasted four times longer than those of competitors and that a replacement cost less than a re-filing job. The company was not above pulling the occasional publicity stunt to get its point across. It once demonstrated the superiority of the Star by employing a well-used blade to cut a bundled dozen of one competitor’s blades into pieces.

Millers Falls Company also marketed Clemson Brothers tempered butcher saw blades. The blades were good enough that the 1894 Millers Falls catalog noted that "after cutting bones for six weeks one of these blades will cut off a half-inch rod of iron in twenty minutes." A modern reader, perhaps unimpressed by the claim, would do well to remember that handsawing iron stock is not for the faint of heart.

The relationship with Clemson Brothers would last forty years—until Clemson terminated the arrangement forcing Millers Falls to begin manufacturing its own hacksaw blades. The quality of the blades produced by Millers Falls soon surpassed those made by Clemson, and the Millers Falls blades, as evidenced by its Blue-Mol and Tuff-Flex products, would remain top-notch into 1960s.(1)

Langdon Mitre Box products

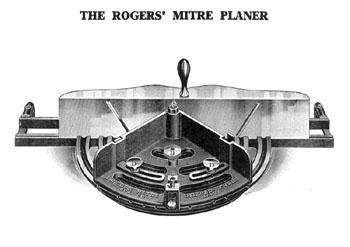

During the 1880s, the Millers Falls affiliation with the Langdon Mitre Box Company began to pay dividends in the form of new products. On September 19, 1882, David C. Rogers was issued patent no. 264,766 for what was to become known as the Rogers miter planer. Manufactured by Langdon and available through the Millers Falls Company, the Rogers miter planer, a deluxe shoot board with a semi-circular frame, was capable of delivering an almost flawless trim of angle cuts on mating pieces of stock. The tool, which cut on both the push and pull strokes, would soon become a favorite of picture framers who valued its versatility, accuracy, and economy of motion. The miter planer was capable of more sophisticated work, however. Two adjustable, lockable guides on its rotating bed plate provided rests which allowed for the precision trimming of the wedge-shaped pieces used to fabricate cylindrical and oval-shaped forms in patternmaker’s shops. The Rogers miter planer was popular enough to remain in the Millers Falls catalog for over four decades.

Joining the Rogers miter planer in the 1880s were two variations on the original Langdon miter box. The New Langdon was developed to overcome one of the major limitations of the original model. The first Langdons had been designed with a set number of saw stops—limiting cuts to a series of predetermined angles. Although still equipped with the convenient stops, the New Langdon miter box allowed the saw to be locked into position at any point between ninety and forty-five degrees. Customers demanding even further flexibility could select a New Langdon Improved miter box. The improved New Langdon featured an adjustable arm which allowed the sawyer to reposition the stock to effect a cut of between ninety and seventy-three degrees. Although the need for the additional capability would appear to have been limited, demand was such that the New Langdon Improved miter box remained a part of the Millers Falls catalog for a half-century. In some ways, advertising appears little changed in the one hundred twenty years since the introduction of the two Langdon boxes. A trip down the aisle of any grocery store still yields a plethora of “new” and “new and improved” products.

Albert Goodell’s patents

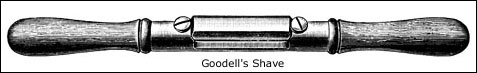

Albert D. Goodell, the young man whose patented brace had been acquired by the original Millers Falls Mfg. Company in 1870, developed a number of tools for the Millers Falls Company in the 1880s. His designs were well thought out and very marketable. On February 19, 1884, Goodell was issued a patent for a cigar-shaped spoke shave that remains popular with woodworkers despite its being out of production for nearly ninety years. The circular shave, with a detachable handle, is an excellent choice for working in cramped quarters or on radiused surfaces. Capable of precise work, with an easily adjustable cutter and comfortable to use, the tool is a paragon of fine design. Goodell assigned the patent to the Millers Falls Company on the day it was registered. Ten months later, he was issued United States Letters Patent No. 310,046 for an improvement to vial adjustments on spirit levels. The Goodell name was soon attached to seven of the company’s new cast iron efforts. Included in the lineup were two small bench levels, a four-inch triangular level, and four double plumb levels. The levels were characterized by ornate cast iron detailing, a black japanned finish, and the new adjustment feature by which the vials, enclosed in metal sleeves, could be manipulated by tightening and loosening small screws at the opposite ends of their containers.

An employee of Millers Falls for nearly two decades, Albert D. Goodell advanced through the ranks of the firm, holding such positions as inspector, master mechanic, and, finally, plant superintendent.(2) He left the Millers Falls Company in 1888 and with his brother Henry founded Goodell Brothers in nearby Shelburne Falls. Their new company made drills, chucks, and automatic screwdrivers, but, interestingly, did not manufacture levels featuring the innovation that Albert Goodell had patented that year. Albert had been issued a patent on October 16, 1888, for yet another vial adjustment mechanism—this one useful on wooden levels. He sold the rights to the Millers Falls Company which used the design when it began to produce wooden levels in 1889. Millers Falls’ foray into the fabrication of wooden levels was a short-lived endeavor. By the time of its 1894 catalog, the firm was no longer manufacturing this type of tool but was listing, instead, Stratton Brothers levels, products it had sold in the 1870s and 1880s. The decision to abandon the production of wooden levels may have been due to the catastrophic fire which destroyed the company’s wood shop in 1890. The Millers Falls Company did not manufacture wooden levels again until 1926.

Certainly, the most complex of the Goodell tools was the treadle lathe that made its appearance in 1885. With a bed just twenty-four inches long and barely capable of accommodating a fifteen-inch piece of stock between its centers, the Goodell lathe was strictly a hobbyist’s product. The basic Goodell sold for ten dollars and included both long and short tool rests, five turning chisels, a wrench, and a set of drill points. For an additional two dollars, a detachable scroll saw head could be added to the apparatus. The cost of a complete Goodell unit—a lathe with detachable saw—was roughly comparable to that of the company’s Lester unit—a saw with detachable lathe. While the Lester had the advantage of being able to cut stock two inches thick, its lathe attachment was limited to stock just nine inches in length.

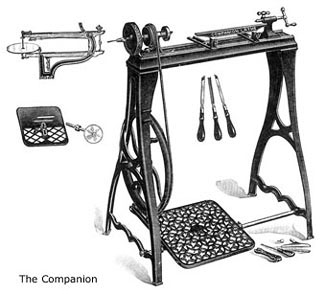

The Millers Falls Company made its appeal to the home hobbyist in a fairly sophisticated way when it developed the Companion, a combination treadle lathe and saw designed exclusively for the youth market. The Companion units were developed in consultation with Perry Mason & Co., the publisher of The Youth’s Companion, a magazine sometimes credited with the popularization of scroll sawing among the younger set. Named after the magazine, the Companion cost $1.50 less than the Goodell model and was heavily promoted in the publication. Perry Mason & Co., mindful of the advertising revenue generated by one of the biggest suppliers to the “Sunday afternoon” saw market, went so far as to award Companion outfits as premiums to young entrepreneurs especially adept at selling subscriptions to its publications.(3)

Products, prestige, and high water

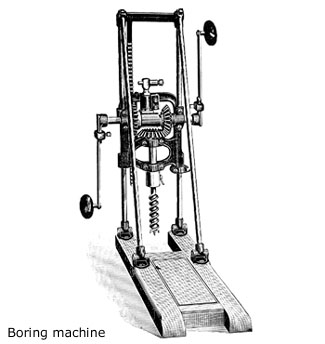

In addition to selling products manufactured by firms such as Clemson Brothers, Langdon Mitre Box, and Stratton Brothers, the company sold Alford hand vises, Johnson automatic boring tools and the Parker & Colburn ox shoes once manufactured by the Greenfield Tool Company. For the most part, however, the company remained focused on that which it did best—selling tools of its own development. Notable among the new products appearing in the catalog was the Millers Falls boring machine, a tool destined to become one of the most popular of its type and which remains highly prized by timber framers today. Boring machines were used for drilling holes in the timbers used in post and beam construction. The large mortise and tenon joints were typically pinned with wooden pegs, and the machines made quick work of a task that had once been the exclusive province of the T-auger. The Millers Falls machine was a high-end model capable of drilling at a variety of angles and equipped with an adjustable stop that automatically reversed the direction of the bit when the hole reached its proper depth.

The success of the Millers Falls Company and its status as one of the area’s major employers lent a certain prestige to the company’s ranking officers. A resident of the town of Greenfield, Levi J. Gunn served as assessor in 1868 and town selectman in 1877. He served as state senator, 1885-1886, and as a member of the Governor’s Council in 1887 and 1888. No doubt his status was increased when the local baseball club wore uniforms featuring his name in the mid-1880s. “With bold three-inch felt letters across their chests and wearing the knotted ties that were part of the uniform of the day, the boys went out to meet good opposition. During the 1886 season, they played 26 games and were victorious in 18 of them, and were rightly called the champions of Northwestern Massachusetts.” If the company secretary, George E. Rogers, felt a bit slighted at the attention being given Gunn, the situation was remedied in 1888, when the town fielded another team, this one bearing the inscription “Geo. E. Rogers” on its uniforms.(4)

Of course, all was not rosy in the 1880s. The Millers Falls Company’s dependence on water power was tested early in the decade when a flood tore away half of its dam. Although such events were not uncommon in nineteenth-century America, they were infrequent enough to be considered memorable a half-century later, and the firm’s response to the challenge would become incorporated into company lore. Production at the company was kept online by bringing in a steam engine to supply the plant with power until repairs could be made. A smaller, portable boiler and generator were brought in to run the vise shop. Compared to the destructive fires that beset the company in its formative years, the loss of the Millers River dam was more in the category of a setback rather than a disaster.(5)

The 1890s

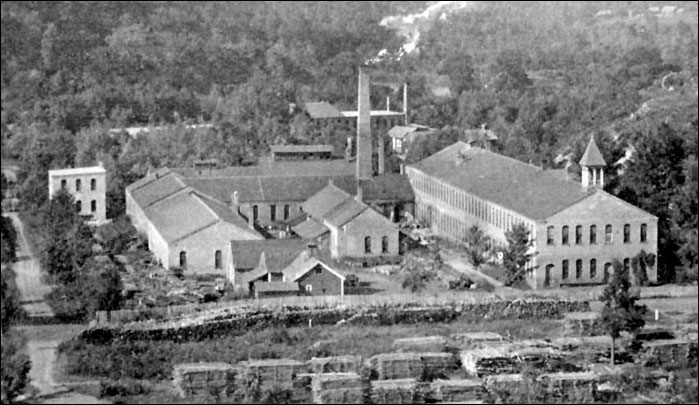

This is the Millers Falls plant as it appeared in 1891. It is taken from an illustration that appeared in a book entitled Picturesque Franklin County, published in that year by Wade, Warner & Company of Northampton. Shown is the side of the plant facing the Millers River, and stacks of logs and lumber are seen in front of the buildings. The main building, on the right, is now two stories for its entire length, and several new additions and smaller structures can be seen. The company was able to report it had 75,000 square feet under roof. The town which had sprung up around the plant now numbered between eight and nine hundred residents, and the operation itself included some two hundred workers—fifty more than in 1879. While George Rogers and Levi Gunn kept an eye on the plant, Henry Pratt and Edward Stoughton worked out of the new company office at 93 Reade Street in New York City. At times referred to as a warehouse, the new location, secured in 1887, was two blocks from the old office at 74 Chambers Street and consisted of “a full store with basements.” The New York office remained at the Reade Street address until 1898 when it was relocated to 28 Warren Street.

The saw business

In a short business notice in the October 1890 issue of The Manufacturer and Builder, the Millers Falls Company was reported to have laid claim to the distinction of being the largest manufacturer of carpenters’ and machinists’ saws in the world. There was some truth to the assertion. The export side of the company’s business was booking orders for 150,000 saws with some regularity, and a 200,000 saw order had been shipped. The firm reported total saw sales running into the millions of units. Considering that the company sold hand-powered bracket, frame, and scroll saws; hack saws; treadle saws; butchers’ saws; and de-horning saws, and that it sold massive quantities of saws to accompany Langdon miter boxes, it is possible that Millers Falls was the leading saw seller in the world. It would be prudent, however, to consider that the company may have chosen to blur the line between the terms “manufacturer” and “seller” in order to make the most of its story.

Millers Falls leveraged its relationship as sales agent for Clemson Brothers hacksaw blades into a profitable line of Star brand hacksaw frames. Steel, cast iron and wooden frames were available, and saws with extendable frames and re-positionable blades were developed. Although the frames were promoted heavily, the line’s success rested on the quality of Clemson’s blades. An advertisement in the January 16, 1897, issue of Scientific American noted:

Our Star Hack Saws are now used in nearly all Ironworking Shops the world over. They are equally useful for farmers and men in all departments of life. They will cut iron and wood equally well. A nail does not dull them at all. One blade, which costs five cents, will cut off an inch square bar of iron 200 times without sharpening. We have cut off such a bar 387 times with one blade.

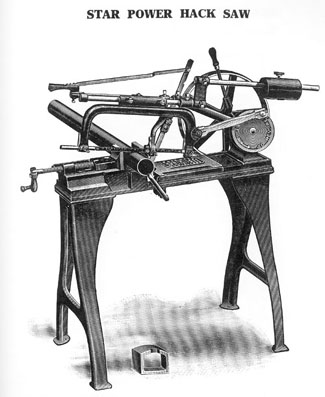

The company credited Henry L. Pratt with the original idea for its Star power hacksaw.(6) The first experimental machine consisted of a crankshaft mounted on a lathe and attached to an arm with a hacksaw mounted on it. A wooden-frame model followed, and metal-frame machines became available as early as 1891. Star power hacksaw machines were the featured exhibit at the Millers Falls booth at the Columbia Exposition in Chicago in 1893. The manufacturer wisely chose to demonstrate the saw in action. Onlookers were amazed to watch a machine sawing through a metal bar at a steady forty-five strokes a minute and then stopping automatically when the cut was completed. Although the rate of cutting was not speedy, company representatives were quick to point out that automated sawing was quicker than using a lathe or planer and far quicker than heating a piece and cutting it with a blacksmith’s hack. The Star power hacksaw received international exposure at the exposition, and one English shop straight away ordered one hundred of them. Oddly, the firm began almost immediately to get requests for hand-cranked hack sawing machines. To accommodate the demand, a heavy drive wheel with a hand crank was designed for the machine and made available at extra cost. Apparently, the company had no problem finding customers who were willing to pay a premium in order to operate their power hacksaws by hand.

William McCoy’s chucks

During the 1890s, a long-standing company employee, William H. McCoy, patented improvements to the two classic chucks mounted on the premium Millers Falls drills and braces. McCoy added a spring to the jaws of the Barber Improved chuck in 1890. The new, self-opening jaws remained the hallmark of the company’s better braces until supplanted by the first truly universal jaws in 1907. McCoy also redesigned the company’s Star chuck in 1896, increasing the number of jaws from two to three and improving its grip on round shanks. The jaws in the new Star were held in place by pins that moved back in forth within recesses cut into the chuck’s socket, remaining in easy alignment when tightened on the shank of a drill. Relatively inexpensive to manufacture and highly reliable, McCoy’s three-jaw chuck was an outstanding piece of work and provided a starting point for what was to become one of the most extensive lines of hand drills ever offered. In addition to his work with chucks, McCoy re-designed the company’s angular bit stock in 1897.(7)

Auger handles

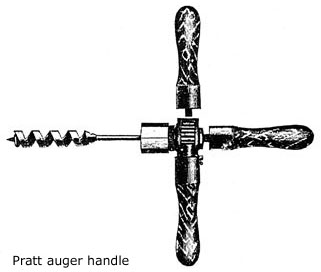

The Millers Falls Company’s 1897 catalog is notable for its four T-auger handles—two of them labeled as Pratt’s, one as Rogers’ and another as Gunn’s.(8) The T-auger handles used by most workmen were simple tools, being little more than a stick with a square hole in the center for holding the bit. In the hands of a burly workman, the device is surprisingly effective with its biggest drawback being that the hands are repositioned at least twice during each rotation of the tool. A worker could easily overcome this difficulty by choosing one of the company’s high-end, ratcheting models (the Gunn model or one of the Pratts). The ratcheting auger handles also made provision for a user finding himself in a situation with inadequate clearance for a full rotation. An arm needed only to be detached and screwed into an opening at the handle’s top to convert the tool into an oversized, ratcheting corner brace. The advent of the more sophisticated boring machines did not, as one might expect, sound a death knell for the traditional T-auger. The T-auger’s easy portability, its flexibility in a variety of work situations, and its modest cost were factors ensuring continuing popularity. Pratt’s auger handle no. 4 was considered the top of the line and cost dealers a mere $24.00 per dozen. The cheapest model, the non-ratcheting Pratt, cost fifty cents each if purchased in similar quantities.

Illustration credits

- Factory view: Picturesque Franklin County. Northampton, Mass.: Wade, Warner & Company, 1891.

- Power hacksaw: Catalogue No. 35. Millers Falls, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1915.

- Pratt’s auger: Catalogue No. 25. New York: Millers Falls Co., [ca. 1897].

- All tools on page: Catalogue No. 35. Millers Falls, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1915.

- Linked image of baseball club: Adie, Allan D. “75 Years of honest endeavor.” Dyno-mite, December 1943.

References

- Although the article in Hardware Dealers Magazine conveniently ignores the fact that Millers Falls was not actually producing its blades, I have placed enough trust in it to use the information about the Stubbs saw and the publicity stunt. I used the Dictionary of American Tools for information on the founding of Clemson Brothers and Roger K. Smith for mention of the soles sales agent relationship. (At some point during the firms’ long relationship, Clemson Brothers instituted direct sales as well.) Dictionary of American Tools. Early American Industries Association, 1999. p. 172; “The Millers Falls Co.” Hardware Dealers Magazine, January 1915, v. 43, no. 253, p. 112-113; Roger K. Smith. Patented Transitional & Metallic Planes in America, Vol. II. Published by Roger K. Smith, 1992. p. 265.

- A digression: Into each life a little rain must fall, and, certainly, some fell into Albert’s in 1885 when his wife became a charter member of the Millers Falls Temperance Union. Pearl B. Care, Anastacia Burnett, and Doris A Felton. The History of Erving, Massachusetts, 1838-1998. Erving, Mass.: Erving Historical Society, 1988. p. 168.

- On the Companion lathe: “The Millers Falls Co.” Hardware Dealers Magazine, January 1915, p. 113.

- Information on the baseball teams is from Care; the dates of Levi Gunn’s local civic contributions are courtesy Thompson; his service at the state level is courtesy Kellogg. Pearl B. Care, Anastacia Burnett, and Doris A Felton. The History of Erving, Massachusetts, 1838-1998. Erving, Mass.: Erving Historical Society, 1988. p. 199; Francis M. Thompson. History of Greenfield: Shire Town of Franklin County, Massachusetts. Greenfield, Mass: isn't, 1904. v. 2, p. 776-777; Lucy Cutler Kellogg. History of Greenfield, 1900-1929. Greenfield, Mass.: Town of Greenfield, 1931. p. 1602.

- With regard to the flood, I have my faith in Adie, who put the flood in the early 1880s, rather than Care, who placed it in the latter 1870s. Allan D. Adie. “75 years of Honest Endeavor.” Dyno-mite, December 1943, p. 19; Pearl B. Care, Anastacia Burnett, and Doris A Felton. The History of Erving, Massachusetts, 1838-1998. Erving, Mass.: Erving Historical Society, 1988. p. 22.

- On Pratt’s contribution and the Columbia exposition: Allan D. Adie. “75 years of Honest Endeavor.” Dyno-mite, December 1943, p. 19.

- McCoy’s self-opening brace jaws were awarded United States Letters Patent No. 421,420; his three-jaw drill chuck, no. 568,539; his angular bit stock, no. 586,053.

- The Rogers auger handle was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 484,050. Pratt’s ratcheting auger handle: United States Letters Patent No. 438,860.