Levi J. Gunn

Levi J. Gunn, the first treasurer and second president of the Millers Falls Company, was born in Conway, Massachusetts, on June 2, 1830. He was the son of a blacksmith (also named Levi Gunn) and Delia Dickinson. The younger Gunn worked at his father’s trade until the age of eighteen and soon afterward hired on at the Conway Tool Company, a manufacturer of wooden planes.(1)

Conway Tool was the successor to Parker, Hubbard & Company, a firm that was also located in Conway. Its principals, Alonzo Parker and Horace Hubbard, were Levi Gunn's future brothers-in-law. Their steam-powered operation had by 1850 grown to the point that its sixty-five hands produced 60,000 bench planes and 130,000 molding planes per year. In April 1850, Daniel Rice II and other investors were brought on board, and Parker & Hubbard was renamed the Conway Tool Company. Before long, Conway Tool employed some eighty men.(2)

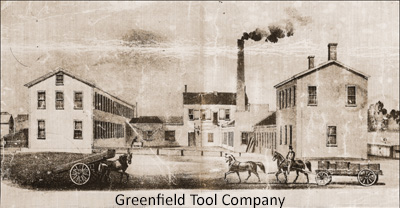

When Conway Tool was destroyed by fire in 1851, Alonzo Parker and Daniel Rice II restarted the operation in the nearby town of Greenfield, renamed it the Greenfield Tool Company, and re-hired Levi J. Gunn to work at the new factory. Gunn’s skills were substantial enough that the job was likely his for the asking. He was one of five men at Greenfield Tool assigned the complex task of making wooden plow planes. Another of Gunn's brothers-in-law, Alvan (Alvin) C. Hitchcock, also worked at the company, specializing in the making of filletster planes. Hitchcock was married toed Gunn's sister Fannie.

The company’s operation included a sawmill. A ledger from the years 1853 and 1854 indicates that most of the timber for planes and packing crates was purchased locally and that the operation generated steam power from the scrap resulting from its manufacturing processes. During these early years, employment ranged between sixty-five and seventy-five men. Those involved in actual production were paid by the piece, with the result that the ledger’s detailed records of wages paid to employees are quite informative. It can be determined, for example, that Levi Gunn specialized in the making of match planes as well as plows. One entry, for July 30, 1853, indicates that he had produced sixty-five plow planes that month. Most of them were made of boxwood, and Gunn earned $80.90 for his efforts.(3)

While at the Greenfield Tool Company, Gunn became acquainted with Charles H. Amidon, a talented planemaker and machinist who hailed from the nearby village of Monroe. The men got on well, and their abilities were such that they soon became holders of the contract for the manufacture of all of the company’s tools. Innovators by nature and interested in production, the pair developed and installed machinery that minimized the amount of handwork going into the operation’s manufactured goods. In 1861, while still employed by the Tool Company, Gunn and Amidon established a small business in Greenfield for the manufacture of household wash wringers.

When it became apparent that the wringer enterprise had a chance of success, the men left their jobs at Greenfield Tool to direct their attention to the new endeavor. Although Gunn initially served as sole proprietor, Charles H. Amidon became a partner in December 1863, and the business was renamed Gunn & Amidon. The company’s primary product was the wood-frame wash wringer Amidon had patented in 1862. It sold well, and an improved version was brought out three years later. The defining moment for the business, however, occurred in 1864, when the partners bought the rights to a bit-brace developed by William H. Barber. Sales of the device were astonishing. The introduction of the brace led to a gradual de-emphasis on the wringer business. Additional bit braces were introduced, and in 1868, new investors were brought in. The business was reorganized as the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company, and work on a new factory at the falls of the Millers River was begun.

Levi Gunn became treasurer of the new company; Henry L. Pratt, a well-to-do lumber dealer, became President. Gunn’s former partner, Charles Amidon, did not serve as an officer but was installed, instead, as plant superintendent. Pratt left for New York City almost immediately to establish a sales office, while Gunn remained on site, serving as general manager of the operation and finding a replacement for Amidon, who left the business two years after it was organized. Owing much of its good fortune to the quality of its boring tools, the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company prospered. In 1873, it merged with the Backus Vise Company, a smaller firm located just next door to its factory. Since Levi Gunn and Henry Pratt held sizable positions in Backus Vise and served as that company’s president (Pratt) and secretary (Gunn), the merger of the businesses was not entirely unexpected. The enterprise formed by the merger was renamed the Millers Falls Company, and under the leadership of Pratt, Gunn, and somewhat later, George E. Rogers, it went on to become one of the country's leading manufacturers of hand tools. A textbook example of New England stability, Gunn’s tenure as Millers Falls Company Treasurer lasted twenty-eight years.

Though he was an innovative and skilled production manager, and in his younger days a talented planemaker, Levi J. Gunn was not an inventor. The company's No. 5 ratcheting auger handle may have borne his name, but it contained no patentable features. Save for an occasional appearance as a witness or assignee, his name is all but absent from the records of the United States Patent Office. Gunn's contributions to the Millers Falls Company's product line were, however, more substantial than they first appear. Raised in the small town of Conway, he was almost certainly well-acquainted with David C. Rogers, the native son who went on to found the Langdon Mitre Box Company and market its products through the Millers Falls operation. Gunn would have been instrumental in arranging for Rogers to move his business to a site within the walls of the Millers Falls plant when Langdon's Northampton production facility was destroyed by flood in 1875. It is probable that the Graves push drills, marketed for decades by the Millers Falls Company, were developed by a male relative on his wife's side—her maiden name was Esther Cowles Graves.

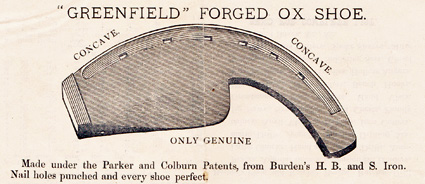

Another of Gunn's contributions to the product line was that of acquiring the rights to the Colburn and Parker patents for the dies used in forging ox shoes when the Greenfield Tool Company was declared insolvent in 1883. Greenfield Tool had been manufacturing shoes under the patents, and when Millers Falls took over the line, it marketed its output as the Greenfield Forged Ox Shoe. The Parker patent, a substantial development of Horace Colburn's original idea, had been awarded to Bowdoin S. Parker, the son of Alonzo Parker and Caroline Gunn, Levi Gunn's sister. In an effort to strengthen the Millers Falls position relative to other manufacturers, Gunn also secured the rights to William Pearce's patent for ox shoe dies.(4) The extra protection did little good; when Gunn sought to enjoin Julius B. Savage and John Deeble from making ox shoes with what he considered to be infringing dies, his case was dismissed.(5)

The Graves family played a significant role in Levi Gunn's life. He married Esther Graves, worked for her brothers-in-law Horace Hubbard and Alonzo Parker, purchased the patent for his nephew Bowdoin's ox shoe dies, and sold popular rosewood-handled push drills under the Graves name.(6) His brother-in-law, Royal Church Graves, operated the Millers Falls office in Boston in the late 1870s, and some of the correspondence between the men has survived. When Gunn was looking for a fashionable new carriage, he asked Graves to investigate the Boston manufacturers. In his return letters, Graves affectionately referred to Gunn as "Brother Levi."(7) When Gunn's wife Esther died in 1897, his brother-in-law became his father-in-law. Royal Graves' daughter Catherine, married her uncle Levi Gunn on July 27, 1899. She was thirty-eight years old, her new husband, sixty-nine.

With the death of Henry Pratt in 1900, the newly wed Levi J. Gunn became president of the company he helped to found—a position he held until his retirement in 1910 at the age of eighty. Though he remained active in Millers Falls Company affairs for over four decades, Gunn chose to reside in the city of Greenfield, rather than in the rough-and-tumble village of Millers Falls, and as his financial prospects improved, he became increasingly involved in the affairs of his community. The former blacksmith’s apprentice lived in a stately home on Main Street, sponsored baseball teams, became active in Republican Party politics, served on the Financial Committee of the local Congregational Church, and sought public office. At one time or another, Levi Gunn served as selectman and assessor in Greenfield, as state senator, and as a member of the Republican State Control Committee. In addition to his holdings in the Millers Falls Company, Gunn maintained a financial interest in the Greenfield Savings Bank, was an incorporator of the Greenfield Electric Light and Power Company, and served as president of the Franklin County Public Hospital. Edward P. Stoughton succeeded Gunn as company president.

Levi Gunn and his first wife Esther were the parents of one child, a son. There is no evidence that the younger Gunn worked for the Millers Falls Company. Levi J. Gunn died in Greenfield on September 9, 1916.

Patents

| Patent Number | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Reissue 10,831 | April 26, 1887 | assignee, by mesne, of William Pearce patent for dies for forging of ox shoes |

| 457,838 | August 18, 1891 | assignee, with G. E. Rogers and H. O. Edgerton of patent for electric stop mechanism |

Illustration credits

- Portrait: Massachusetts of To-day: a Memorial of the State, Historical and Biographical ... Boston : Columbia Publishing Company, 1892.

- Greenfield Tool Company: The Mechanick's Work Bench, No. 10, August 1980.

- Gunn's auger handle: Catalogue no. 24. New York : Millers Falls Company, [no date, ca. 1895].

- Ox shoe notice: Forged Concave Ox Shoes, Millers Falls Vises, Oval Slide Vises, Mechanics' Vises, Jack Screws Manufactured by the Millers Falls Company, Millers Falls, Mass. [S. l] : Millers Falls Company, [1884?].

- Levi Gunn house: Greenfield: One Hundred Fifty Years Old. Greenfield, Mass.: C. Moody, 1903.

References

- General information on Levi Gunn: Biographical Review: Sketches of the Leading Citizens of Franklin County, Massachusetts. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company, 1895. p. 285-286; “Gunn Made Big Dream Come True.” In: A Century of Experience: Millers Falls Company. Greenfield, Mass.: Greenfield Record, Gazette and Courier, August 13, 1968; Daniel P. Toomey and Thomas C. Quinn. Massachusetts of To-day: a Memorial of the State, Historical and Biographical, Issued for the World’s Columbian Exposition at Chicago. Boston: Columbia Publishing Company, 1892. p. 583.

- On Parker & Hubbard and Conway Tool: Emil and Martyl Pollak. A Guide to Makers of American Wooden Planes. 4th edition. Mendham, N. J.: Astragal Press, 2001. p. 100, 311.

- On Greenfield Tool: Donald and Anne Wing. “The Workings of a Plane Factory.” The Mechanick’s Workbench. Catalog No. 10, August 1980, p. 3, 10-11.

- Parker: United States Letters Patent No. 123,927, reissued as No. 6113; Colburn: United States Letters Patent No. 102,372; Pearce: United States Letters Patent No. 314,189, reissued as No. 10,831, United States Letters Patent No. 314,192.

- The Federal Reporter. Vol. 25: Cases Argued and Reported in the Circuit and District Courts of the United States: October 1865-February 1866. St. Paul: West Publishing Company, 1886. p. 101-103.

- R. C. Graves. Letters to Millers Falls Company, Millers Falls, Massachusetts, July 15, 1879; July 17, 1879. Two from a packet of forty-seven letters. Private collection.

- I have no hard evidence linking the extended Graves family to the drill. A number of his wife's extended family were involved in tool manufacture or sales and are likely candidates for its development.