Millers Falls Company Biographies

Included here are biographies of individuals associated with the Millers Falls Company, its earlier incarnations, and its later acquisitions. The firms include the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company, the Goodell-Pratt Company, the Q. S. Backus Company, and the various business enterprises of Charles H. Amidon. Some of the biographies are unique to this part of the website; others consolidate information scattered throughout the various narratives. Virtually all of the entries contain at least some new information.

The biographical pages are a by-product of my research into the history of the company. At the outset, they were little more than the notes that I had compiled to assist in the project. As time passed and the notes became more fulsome, I polished them up and created this page. To the notes, I added links for digital versions of several biographical articles I’ve written.

I’ve made no effort to systematically document the Millers Falls Company leaders and have no plan to do so. The contents of this part of the site reflect my research interests and some of the snippets of information that have come my way. Relatively minor figures are included. I will be adding to the biographical information as I encounter new material. If the information included in these pages had been systematically included in the site’s narrative history of the company, the result would have become a cluttered, unwieldy mess.

Amidon, Charles H.

Charles Amidon was one of the founders of the Millers Falls Company. His biography is available via the link above.

Amidon, Solomon H.

Solomon Amidon, a contractor and younger brother of Charles H. Amidon, built 140 houses in the Millers Falls area. Born in Monroe, Massachusetts, on September 28, 1840, he was the sixth son of David Amidon, a shoemaker, and Bertha Dunbar. Amidon attended academy at North Adams and then moved to Greenfield where he spent three years in the employ of the Greenfield Tool Company. As did so many of his generation, Amidon volunteered to serve his county by enlisting in the Union Army to fight in the Civil War. A member of Company G of the Tenth Massachusetts Regiment of Volunteers, he was promoted to corporal, served a three-year hitch, and on discharge, returned home to the Greenfield Tool Company and carpentry work.

Amidon relocated to Alton, Illinois, in 1865, did not find it to his liking, and several years later returned to Massachusetts where he took up residence in the town springing up around the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company. There, he partnered for a time with Jesse Newton, building homes, churches, and commercial structures. “Sol and Jesse” built a two-story, forty-by-sixty-foot brick building on the Millers Falls Company’s canal to serve as their headquarters and as manufactory for Amidon & Newton, producers of small hardware items. On March 26, 1872, Solomon Amidon was issued United States Letters Patent No. 124,999 for a stay brace for trunk lids, and while it is not known if the design was ever produced, it is indicative of the sort of hardware manufactured by the partners.

The Amidon & Newton partnership was short-lived, as was Solomon’s foray into manufacturing. Amidon elected to remain in the construction business. Certainly one of his more interesting undertakings was the building of a dam across the Millers River. Eighteen feet high and 200 feet long, the structure furnished power for an electric railroad that ran between Millers Falls and Greenfield.

- Sources:

- Biographical Review: Sketches of the Leading Citizens of Franklin County, Massachusetts. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company, 1895. p. 168-171.

- “Millers Falls.” Gazette and Courier. (Greenfield, Mass.), October 17, 1870; January 2, 1871; January 30, 1871; February 27, 1871.

Backus, Quimby S.

Quimby S. Backus sold his vise-making business to the Millers Fall Company in 1873 and then went on to start a series of businesses. His biography is available via the link above.

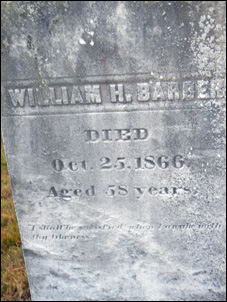

Barber, William H.

May 24, 1864, William Henry Barber was issued United States Letters Patent No. 42,827 for a holder of bits and other small tools. The ’holder’ described in the patent consisted of a rotatable shell that enclosed a pair of spring-loaded, adjustable jaws. Charles Amidon and Levi Gunn, partners who were to become principals in the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company, purchased Barber’s patent in 1865 and began building a wrought iron brace that featured the new chuck. The reputation of the Barber brace spread quickly, tens of thousands were sold, and its profitability became the foundation on which the Millers Falls Company was built.

William H. Barber, the son of John Barber, was born and raised in Franklin County, Massachusetts. He married Caroline Hayward, the daughter of Hampshire County resident Stephen Hayward. The couple settled in Ashfield, a town not far from William’s birthplace, and there, their children were born. The couple parented three sons and a daughter: Henry H., Ernest, James T., and Fidelia. At some point, William Barber picked up the trade of machinist, and the family relocated to Windsor, Vermont, where William worked at the local armory building muskets for Union troops fighting the Civil War. During his employment there, he invented his now-famous chuck. Barber returned to Franklin County about 1865, settled in the Greenfield area, and died October 25, 1866. On February 6, 1872, the patent for William Barber’s chuck was assigned by mesne to the Millers Falls Mfg. Company (Reissue no. 4,736).

- Sources:

- The History of Eau Claire County, Wisconsin, Past & Present: Including an Account of the Cities, Towns and Villages of the County. Chicago: C. F. Cooper, 1914. p. 643-645. (From biography of his son, James Tilly Barber.)

- Headstone photograph courtesy of Judy Winn Graves.

Brown, Otis E.

Otis E. Brown served as the seventh president of the Millers Falls Company. Formerly Vice-President of Personnel for Pendleton Tool, an Ingersoll-Rand subsidiary, Brown arrived in Greenfield in December 1965 to serve as Chief Executive Officer. He became company president three months later when John Owen left the position to become a fund-raiser for Deerfield Academy. Otis Brown headed the company during some of its darkest hours. The operation, plagued by declining sales, an aged physical plant, and a parent company tone deaf to the demands of the consumer hand tool market, was suffering substantial losses. He left the company in 1968 and relocated to Arizona. A native of Fort Thompson, Oklahoma, Brown was the holder of an industrial administration degree from the Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration and an MBA from the Stanford Graduate School of Business. He served in the United States Navy from 1942 to 1946.

Source: “Brown Succeeded Owen as Head of Millers Falls Company.” In: A Century of experience: Millers Falls Company. Greenfield, Mass.: Greenfield Record, Gazette and Courier, August 13, 1968. unpaged.

Dunbar, Henry M.

Henry M. Dunbar (Henry Miles Dunbar) was an employee of the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company at the time that it was located in Greenfield. He lost four hundred dollars in tools and stock in the December 1868 fire that destroyed the operation’s factory. In 1871, Dunbar became an investor in the Amidon Manufacturing Company, the baby coach manufacturer established by Charles H. Amidon after he left the Millers Falls Mfg. Company.

Henry Dunbar was the son of Charles Dunbar, one of the Connecticut Dunbars who migrated to the Monroe area of Franklin County in the early decades of the nineteenth century. The Dunbar and Amidon families were close. Charles Amidon’s mother, Bertha, was a Connecticut Dunbar; he and Henry M. Dunbar were likely cousins. According to the 1850 federal census, the parents of the two men shared a household in 1850.

- Sources:

- “A Destructive Fire in Greenfield.” Gazette and Courier. (Greenfield, Mass.), January 4, 1869.

- “Millers Falls.” Gazette and Courier. (Greenfield, Mass.), Dec. 18, 1871.

Fisk, Charles E.

A carriage maker by trade, Charles E. Fisk was one of the principals in Amidon & Fisk—the baby coach manufacturer established by Charles H. Amidon in 1870 after he left the Millers Falls Mfg. Company. The federal census taken in the summer of that year indicates that Fisk, his wife, and family shared a household with the Amidons. Sadly, a fire in January 1876 destroyed the partners’ baby carriage factory, bringing an end to production. Seven months after the fire, a notice that Charles E. Fisk had opened a carriage-making shop in Greenfield appeared in the Gazette and Courier.

- Sources:

- “Millers Falls.” Gazette and Courier. (Greenfield, Mass.), October 17, 1870; January 30, 1871; February 27, 1871.

- “Greenfield Items.” Gazette and Courier. (Greenfield, Mass.), October 2, 1876.

Gunn, Levi J.

Levi Gunn was one of the founders of the Millers Falls Company. His biography is available via the link above.

Holland, Ashley

Ashley Holland built the dam for Gunn & Amidon’s factory on Cherry Rum Brook in 1862. A machinist by trade, Holland was twice widowed and married to his third wife, the former Lucinda Woods, at the time that he was involved with the construction. At one point, the editor of the Gazette and Courier refers to the fledgling enterprise as Gunn, Amidon & Holland. The usage may have been informal—it is not known if Holland was ever a partner in the operation. Ashley Holland was born in Belchertown, Hampshire County, Massachusetts, in 1808. He died in Ashtabula, Ohio, in 1886.

- Sources:

- “Greenfield Items.” Gazette and Courier. (Greenfield, Mass.), July 28, 1862.

- Thompson, Francis. History of Greenfield: Shire Town of Franklin County, Massachusetts. Greenfield, Mass.: T. Morey & Son, 1904. p. 189.

Huxtable, L. Garth

Garth Huxtable was an independent industrial designer associated with the Millers Falls Company from 1948-1970. His biography is available via the link above.

Huxtable, Robert W.

Robert Huxtable’s career at the Millers Falls Company was one characterized by hard work and ongoing advancement. Although he was hired as a draftsman, Huxtable’s drive and ability to work well with others led to a promotion to head of his department and a larger role for his unit in the development of new tools. A believer in self-directed learning and the pursuit of educational opportunity, Huxtable studied nights to become an engineer and eventually was promoted to Chief Engineer & Supervisor of Quality Control for the hand tools area. He remained with the firm until his retirement—a departure coinciding with the wave of staff cuts that decimated the ranks of the company’s middle management in the early 1970s.

R. W. Huxtable’s influence on the design of Millers Falls’ post-war hand tools was profound. When the firm contracted for outside design work, he worked to ensure that his younger brother Garth had a chance to present his ideas. At the time, Garth Huxtable was already an accomplished industrial designer and in the process of setting up his own shop. He viewed the opportunity to work with the company as a welcome chance to provide some security for his fledgling business. The younger Huxtable had to prove himself as he was not the only designer interested in working with the company. Francesco Collura—like Huxtable a member of the prestigious Society of Industrial Designers—had designed and patented a futuristic-looking hacksaw for the business in 1945. The saw, featuring a lever-action blade tensioner, was fitted with red plastic handles and put into production in 1948, the year that another of Collura’s designs, an exotic-looking hand drill, was added to the line. Collura’s work for Millers Falls was not extensive; L. Garth Huxtable soon established himself as the company’s primary, and later, its sole, outside designer.

The stunning tools of Francesco Collura and Garth Huxtable exerted a pull that proved hard for Robert Huxtable to resist. His drafting table was soon covered with designs for a bench plane with a red plastic handle and knob. Robert Huxtable’s plane was introduced in late 1949, and he was awarded United States Design Patent No. 159339 for it in 1950. A draftsman rather than designer, Robert Huxtable’s plane was a re-work of a tool developed by Samuel Oxhandler for the Sargent Company of New Haven, Connecticut, and was cited as such in the patent papers. The distinctive, forward-looking tools that the Millers Falls Company developed during this period have since been nicknamed the “Buck Rogers” tools because of the similarity of the bench planes to the ray guns carried by actors in science-fiction films of the 1940s and 50s.

Portrait courtesy “Three of Our Engineers Honored.” Dyno-mite (April 1955), p. 14.

Langdon, Leander W.

Leander W. Langdon, invented the Langdon Miter Box, a product that was sold by the Millers Falls Company for over a century. His biography is available via the link above.

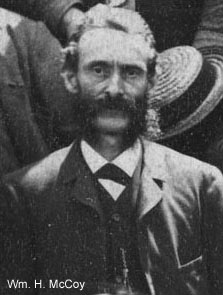

McCoy, William H.

William H. McCoy was a talented machinist who eventually became the superintendent of the Millers Falls Company. A longtime employee who began working for the firm in the early 1870s (when it was known as the Millers Falls Mfg. Company), McCoy served as plant superintendent in the 1890s and the first years of the twentieth century. His position involved a good deal of responsibility; the superintendent managed all aspects of the production side of the operation.

McCoy was an inventor as well as a manager and registered seven patents during his years with the company. The earliest, awarded on August 15, 1871, was for a bit brace with a rotating wrist handle. While the idea of a rotating handle was not new, McCoy's version was equipped with metal ring inserts that kept the wooden handle from splitting and improved the ease with which it turned. McCoy's handle came to be used on the firm's better bit braces. McCoy registered two other patents in the 1870s: United States Letters Patent No. 118,483 for an improved tool handle, and United States Letters Patent No. 146,262 for a drill chuck. Neither design appears to have been produced.

After he became superintendent, McCoy registered two drill chuck patents, both of which were successful and found their way into Millers Falls production. The first, United States Letters Patent No. 421,420, was awarded in 1890 for a self-opening, two-jaw chuck for use on bit braces and breast drills. The chuck, with its spring-loaded jaws, was the first successful attempt to update the company's venerable Barber Improved Chuck and remained in use for nearly two decades. A half dozen years later, McCoy was issued a patent for what would be his finest design, a three-jaw, springless drill chuck. United States Letters Patent No. 568,539 covered the chuck. Its jaws were held in place by pins that moved back in forth within recesses cut into the chuck's socket. The arrangement allowed the jaws to remain in easy alignment as they are tightened on the shank of a drill. Relatively inexpensive to manufacture and extremely reliable, McCoy's chuck may well have been the best springless chuck developed for the eggbeater hand drill.

In 1894, McCoy teamed up with Millers Falls Company president Henry L. Pratt to patent a spiral screwdriver. Awarded United States Letters Patent No. 529,401, the design found its way into the Millers Falls Company's catalog as the No. 11 and 12 spiral screwdriver series. Three years later, McCoy re-designed the firm's adjustable angular bitstock, replacing a slotted locking mechanism that was prone to slippage with a secure rod and thumb-nut assembly. McCoy's adjustment was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 568,058.

In 1903, poor health forced William McCoy to retire from an active role with the Millers Falls Company, and his assistant, William G. Stebbins, assumed his responsibilities. William H. McCoy passed away on September 21, 1905.

- Sources:

- "Death of Millers Falls Superintendent" Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) September 23, 1905, p. 1.

- Portrait courtesy Erving Historical Commission. Enlargement of a section of an 1880s photo of a group of Millers Falls Company employees.

Moore, James

Although never an officer in the organization, James Moore was one of the major investors involved in founding the Millers Falls Mfg. Company. Moore became involved in the venture by virtue of his ownership of the one-hundred-acre tract that became home to the company’s factory, but he was to die tragically less than a year after the firm was organized. A bolt on one pole of his horse-drawn carriage came loose, causing his spirited team to bolt. Entangled in the reins of his runaway team, Moore was dragged about an eighth of a mile and sustained severe head injuries. Thirty-six employees of the Millers Falls Mfg. Company attended the funeral. Moore was born in 1821 in the state of Connecticut; his wife, Priscilla, was born in New Hampshire.

- Sources:

- “Fatal accident.” Gazette and Courier. (Greenfield, Mass.), June 14, 1869.

- “Millers Falls.” Gazette and Courier. (Greenfield, Mass.), November 4, 1872.

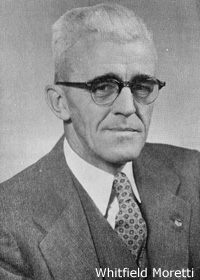

Moretti, Whitfield

Whitfield Moretti was the developer of the Millers Falls Company’s first electric drill. Born in New York City on December 19, 1895, he graduated from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1918 and went to work as assistant to the steam engineer for the Donner Steel Company in Buffalo. When the Steel Strike of 1919 forced the closure of the plant, he moved to Syracuse, New York, where he took a job as a draftsman for a company manufacturing motor trucks. The truck plant closed a few months later, and Moretti found himself once again unemployed—an unhappy situation for a young man with a fiancée looking to set a date for their nuptials. In August 1920, “Whit” Moretti hired on as a draftsman with the Millers Falls Company. He married his fiancée wife a month later.

Moretti’s abilities were considerable. After several years at the drafting table, he was transferred to the Methods Department to do time studies, set rates for piece work, and look at improvements in manufacturing processes. He did well and in 1925 was assigned the task of developing the company’s first electric drill. The project was a difficult one as the organization had no experience in manufacturing electric tools. The drill Moretti’s team came up with—the No. 414—featured a quarter-inch drive and was so well-designed it remained in production for over thirty years. Whit Moretti soon became the driving force behind the design of the company’s electric tools. After the retirement of William J. Parsons in 1941, he was appointed Chief Engineer of the Electric Tool Division. Twenty years later, he became Director of Engineering.

Whit Moretti initiated work on the development of the company’s “shock proof” electric tools when he assigned his second-in-command, Leonard Pratt, to the project in the late 1950s. The shock proof tools were developed in response to the inadequacies of the three-prong plug that was required for approval by the National Electrical Code and Underwriters Laboratories. The plug’s third prong provided a ground that was intended to protect a user in the event of a power leakage from a worn or defective tool. At the time, however, most electrical outlets accepted only two-prong plugs, so users often removed the third prong—destroying the safety feature and leaving the operator liable to electric shock. On the basis of tools returned for repairs, it was estimated that one-half of all the portable power tools in the United States that had been equipped with three-prong plugs had had the safety prong removed. A number of users were electrocuted as a result of the alterations. The situation was much improved when Millers Falls Company became the first United States manufacturer to develop and market double-insulated tools.

Whitfield Moretti retired in 1962 and died in Turners Falls, Massachusetts, on February 12, 1989, at the age of 93.

- Sources:

- “He Fathered our First Electric Drill.” Dyno-mite. (August 1955), p. 12-14.

- “Moretti Initiates Start of Shock-Proof Research.” In: A Century of Experience: Millers Falls Company. Greenfield, Mass.: Greenfield Record, Gazette and Courier, August 13, 1968.

- “Two Senior Old Timers.” Dyno-mite. (September 1960), p. 12-13.

Owen, John J. (Jack)

John J. Owen, the sixth president of the Millers Falls Company, was born on February 16, 1916. He is the son of Leartus Gerauld Owen, an army surgeon, and Ethel Christine Rogers, the daughter of George E. Rogers, the longtime company secretary who went on to become treasurer, vice-president, and general manager of the Millers Falls Company. Usually referred to as “Jack,” John Owen earned his bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering at the University of Virginia and started working for Millers Falls after a short stint at Westinghouse Electric. He enlisted in the United States Army in the weeks following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and was discharged in 1946 with the rank of major. Two years later, he returned to the Millers Falls Company to work as a mechanical engineer. He soon became head of the Mechanical Engineering Department but returned to active duty in 1950 to serve in the Korean War effort.

His war service at an end, Owen joined the Institute of Textile Technology, but he returned to the Millers Falls Company, in 1952, as assistant plant superintendent. Prior to his elevation to company president in 1962, he held positions as advertising manager, assistant to the executive vice-president, executive vice-president, and as member of the board of directors. Jack Owen engineered the sale of the company to Ingersoll-Rand in 1962—retaining the presidency until March 1966 when he went on to become a fund-raiser for the Deerfield Academy. In 1968, Owen accepted another fund-raising position—as director of corporate relations—at Yale University. In 1976, after eight years at Yale, he went on to become vice president for development at the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, where he remained until his retirement a decade later.

- Sources:

- “Jack Owen—Relaxed, Alert.” Greenfield Recorder Gazette (Greenfield, Mass.), Dec. 19, 1962.

- “Former President Turned to Field of Education.” In: A Century of Experience: Millers Falls Company. Greenfield, Mass.: Greenfield Record, Gazette and Courier, August 13, 1968.

- Telephone interviews with John J. Owen, January 5, 2005, and March 5, 2005.

- On this site: John Owen, Company President.

Parsons, Charles W.

The son of William J. Parsons, the Chief Engineer for the Millers Falls Company, Charles W. Parsons worked at the company for fifty-two years. He signed on with the company in 1910 and spent his first two decades laboring in the Payroll and Cost Study Department. Early in his career, he introduced the company’s first cost accounting system. Prior to this time, there were two predominant ways for determining the cost of a product: one was by the weight of the item, the other involved foremen setting a piece price for each of the different operations used in creating the various parts of a tool.

Between 1931 and 1963, Charles Parsons served as the company’s purchasing agent, the person responsible for acquiring all of the goods and supplies needed for production. Parsons was dedicated to his job—arriving early, eating at his desk, and eschewing coffee breaks. The twenty to forty salesmen per day who stopped at his office were greeted by a sign that read: “State your business as briefly as possible as my time is valuable.” An article in the company employee’s magazine, Dyno-mite, noted:

A familiar site was Charlie interviewing a salesman (with the telephone interrupting several times), issuing orders at the same time to the girls in the outer office who kept darting in and out in answer to his knee-operated call bell. In the meantime he was doing clerical work with his free hand (to hold down the overhead) ... You had to do four things at once to keep up with him.

The retirement of old-time purchasing agents like Parsons represented the end of an era as office automation and new methods of procurement made fundamental changes to the nature of the work. At the time of Parsons’ retirement, his son, William (also known as ’Bud’), was working for the Millers Falls Company as Assistant Sales Promotion Manager. Bud Parsons was the third generation of his family to be involved with the business.

- Sources:

- “A Period of Service.” Dyno-mite, (December 1960), p. 12-13.

- “An Old-time P. A.” Dyno-mite, (December 1962), p. 12-13.

Pratt, Henry L.

Henry L. Pratt was one of the founders of the Millers Falls Company. His biography is available via the link above.

Pratt, Leonard C.

Leonard C. Pratt was Vice-President and Director of Engineering for the Millers Falls Company. He played the leading role in the development of its double-insulated electric drills. His biography is available via the link above.

Pratt, William M.

A director of the Millers Falls Company. William M. Pratt is most notable as the founder of the Goodell-Pratt Company, a business absorbed by Millers Falls in 1931. His biography is available via the link above.

Proven, John A.

John A. Proven became the Millers Falls Company’s executive vice-president for sales on March 1, 1956. Proven, formerly a vice president and director of the Porter-Cable Machine Company of Syracuse, New York, took the controversial step of bypassing the hardware wholesaler network to sell directly to dealers. The move would complicate the distribution of the company’s products for the next quarter century.

- Sources:

- “Millers Falls Company Appoints High Officer.” New York Times. February 11, 1956. p. 35.

- Telephone interview with John J. Owen, former company president, March 5, 2005.

Rogers, George E.

George E. Rogers was the Secretary, and later Treasurer, of the Millers Falls Company and a longtime majority owner of the Langdon Mitre Box Company. His biography is available via the link above.

Rogers, Philip

Philip Rogers, the fifth president of the Millers Falls Company, was the son of long-time company secretary and later, treasurer, George E. Rogers. His biography is available via the link above.

Rose, Clemens B.

Clemens Belden Rose was a carpenter and mechanic who developed a bit brace that was later manufactured by the Millers Falls Company. His biography is available via the link above.

Sawyer, Samuel

On August 15, 1871, Samuel Sawyer of Erving, Massachusetts was issued United State Letters Patent No. 118,058 for a method of securely fastening rotating heads to the frames of bit braces. Sawyer’s method of attachment resulted in a head less likely to separate from the quill when under pressure and, as no large screws were involved, less likely to split.

Sawyer was born on May 3, 1836, in Richmond, New Hampshire where his father, John M. Sawyer, farmed and operated a saw mill. In 1848, the elder Sawyer moved with his wife and four sons to Winchester, New Hampshire, where, after completing his education, Samuel worked in a sawmill. In 1856, Samuel Sawyer married Sarah H. Starkey, of Keene, New Hampshire. She died in the tenth year of their marriage, and Samuel chose as his second wife, Sarah S. Pratt, the sister of Henry L. Pratt, long-time president of the Millers Falls Company.

Sawyer’s tenure at his father’s sawmill in Winchester was not a long one. He soon moved to Orange, Massachusetts, where he worked in a foundry until the operation was destroyed by fire. After the fire, he found work as a millwright for the turbine manufacturer Hunt, Wait & Flint, the predecessor to the present-day Rodney Hunt Company, a firm still located in the town of Orange. Sawyer left the enterprise in 1869 to supervise the building of the dam and factory for the Millers Falls Mfg. Company. On completing the project, he leased the sawmill on the Millers Falls property and conducted a custom sawing operation for several years. During this time, he developed a patented method for attaching heads to braces. Restless, he then left the area to work in the construction business in New York and Michigan but returned in 1877 to long-term employment as a wood turner with the Millers Falls Company. In February 1896, Samuel H. Sawyer died of a heart attack in the train station at Millers Falls. He was 59 years old

- Sources:

- Biographical Review: Sketches of the Leading Citizens of Franklin County, Massachusetts. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company, 1895. p. 86-87.

- "Sudden Death of a Well-Known Man." Vermont Phoenix. Feb. 14, 1896. p. 3.

- Portrait courtesy Erving Historical Commission. Enlargement of a section of an 1880s photo of a group of Millers Falls Company employees.

Stebbins, William G.

William G. Stebbins succeeded William H. McCoy as superintendent of the Millers Falls Company in 1903. Stebbins was born in Conway, Massachusetts, on June 7, 1857. At age 16, he took a job with the Millers Falls Company grinding castings and oiling shafting. By 1886, he had become foreman of the Brace and Hand Drill Departments and five years later became Assistant Plant Superintendent. When he was promoted to the superintendent position, it was on the basis of his management skills rather than his ability as a machinist or inventor. Stebbins was involved in the registration of only two patents during his career with the company. In 1915, he was promoted to Works Manager, a job that focused more on the administrative side of the operation rather than daily production.

The first of Stebbins' patents was a collaborative effort with John A. Leland, at the time one of the most talented and inventive of the company's machinists. The men were issued United States Letters Patent No. 942,572 for a collapsible push drill. The ingenious design allowed for the creation of a compact, pocket-sized drill with enough free space in the outer tube to allow for a bit magazine. The patent became the basis for the company's No. 8 Automatic Star Pocket Borer. Stebbins' second patent, United States Letters Patent No. 989,203, was for a thrust bearing for the wrist handle of a bit brace.

His long tenure with the firm made Stebbins the go-to guy for newsletter editors looking for details on the company's earliest days. From Stebbins they learned that drinking water was fetched from the canal in buckets and brought back to the workroom and that lighting was supplied by flickering kerosene torches so smoky that the air in the factory took on a bluish cast. In the coldest days of winter, ice in the mill race became a major headache and workers would spend nights chopping and shoveling in the wheel pit to ensure power for the next day's production. In his final years with the company, Stebbins served as the operation's purchasing agent.

- Source:

- "William G. Stebbins." Brace Bits. v. 5, no. 5 (March 1921), p. 3.

Stoughton, Edward P.

Edward P. Stoughton was the first vice president and the third president of the Millers Falls Company. He later became Chairman of the Board of Directors. His biography is available via the link above.