The Goodell Brothers' Companies

Albert D. Goodell and Henry E. Goodell

The story of the Goodell Brothers' companies begins with a small business founded in 1866 by two of the five sons of Vermont-born farmer Anson Goodell and his wife Lucy Rice. The brothers, Albert and Henry, left their native state and established a small manufacturing operation in Buckland, Massachusetts. Working inside the Perry & Demming building on the banks of the Clesson River, the young men—Albert was twenty-one and Henry barely eighteen—made pieces for wooden chairs, and later on, small hardware items.(1)

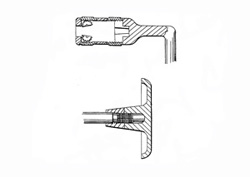

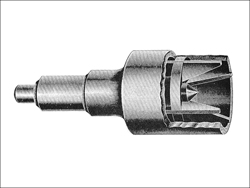

In 1868, Albert patented a bit brace with a ring-type chuck. Though the patent documents list his place of residence as Florence, Massachusetts, he may not have spent much time there. Florence was the home of his older brother, Dexter, who had patented a brace with ring-type chuck some three years earlier.(2) The external appearance of Albert's chuck bore a striking similarity to that developed by Dexter. The internal arrangement of the device was another matter—Dexter's design featured an impractical four-jaw chuck with a rubber spring; Albert's ingenious chuck was equipped with two jaws and was springless. There is no evidence that Dexter Goodell's brace was ever put into commercial production.

Albert's appearance in Northampton and the external similarity of his chuck to that of his elder brother suggest Dexter W. Goodell as the source of inspiration for his foray into tool design. Apparently, he sought his brother's advice on the patent process. Dexter Goodell's patent application had been witnessed by his attorney J. B. Gardiner; three years later, Albert was represented by the firm of J. B. Gardiner & Edward Hyde. In 1870, not long after Albert and Henry Goodell began producing Albert's brace in Buckland, their efforts caught the attention of the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company. Whether from a desire to stamp out competition or a belief in the tool's marketability, in 1871 Millers Falls made Albert an offer he couldn't refuse. He sold his patent to the much larger company for $10,000, and he and his brother signed on as Millers Falls employees.(3) Goodell's 1868 brace remained in the Millers Falls lineup for some six to eight years—until the time that the company began to pare its brace offerings to focus on its Barber and Barber Improved models.

The Goodell brothers were talented and brought much to the Millers Falls Manufacturing Corporation. Albert Goodell rose to the position of master mechanic and later replaced Edward Lester as plant superintendent; Henry became a foreman and accomplished machinist. Albert was the more inventive of the pair, patenting a number of tools while employed at the Millers Falls plant and dutifully assigning his employer the rights to his designs. In this manner, the company acquired the patents to a pair of ratchet braces, four chucks, an adjustment mechanism for iron spirit levels, a blade holder for scroll saws, and a cigar-shaped spokeshave. The Langdon Mitre Box Company, an independent business owned by Millers Falls board member George E. Rogers and located within its factory, benefited from the abilities of A. D. Goodell as well. Goodell and Rogers family patriarch David C. Rogers developed and patented a highly successful miter box, the New Langdon. The New Langdon Miter Box would remain in production until the early 1930s.

The Goodell Brothers Company

Given their obvious talents, it is not surprising that in 1888 Albert and Henry E. Goodell left the Millers Falls Company to start a business of their own. They located their new enterprise in Shelburne Falls, a village on the Deerfield River just five miles from the site where they first set up business some twenty years earlier. Operating as the Goodell Brothers Company, they began the manufacture of boring tools, clamps, chucks, and automatic screwdrivers. During their four-year partnership, the brothers developed and jointly patented two automatic screwdrivers, a push drill, a butt gage, and a rasp for removing pegs and nails from the insoles of shoes.

Note: The author is aware of the striking similarities in the appearance of the individuals identified on this page as Albert and Henry Goodell. The image of Albert D. Goodell is a photograph of the original labeled portrait at the Shelburne Historical Society—an organization located in a community where he was a leading businessman and long-time resident. The image of Henry E. Goodell, a Greenfield resident, is one he had placed in a county history. Despite the similarities, I've assumed a strong family resemblance and accept both identifications.

Goodell Brothers' first push drill—soon to be identified as the No.1—was a small nickel-plated tool similar in design to the brass-barrelled Johnson & Taintor push drills sold by Millers Falls Company and other hardware firms. Identical to the Johnson & Taintor in length and diameter, and with a copycat chuck, the Goodell Brothers No. 1 push drill was sold in a tin box virtually indistinguishable from that of its competitor. Like the Johnson & Taintor drill, the bits did not store inside the handle of the drill but in a small wooden tube shipped inside the box. Shortly after the drill appeared, another version of the No. 1 was introduced, this time with a wooden handle. It was called, appropriately enough, the No. 2. In 1891, the company patented an improved version of its No. 1 drill—one that provided for the storage of bits in its handle. Each bit was stored in its own cell, and a rotating cap, with a single hole in it, provided access to the bits—one cell at a time. The new drill, called the No. 3, was an addition to the line and did not replace the earlier models.

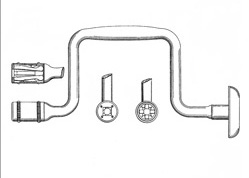

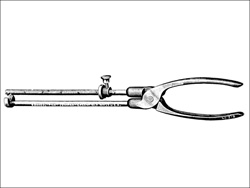

A pair of patents, issued to the Goodell Brothers in 1890 and 1891, defined the specifics of a practical, well-designed spiral screwdriver. Typical of its time, the screwdriver featured a single spiral that functioned to drive screws but could not be reversed to extract them. Unique to the Goodell design, however, are a pair of projections on the front socket that automatically engage a pair of notches in a socket attached to its handle when the tool is closed. When so engaged, the projections lock the screwdriver so that it can be used in the traditional manner—a feature handy to a user encountering a recalcitrant screw. The screwdriver automatically unlocks itself each time the handle is raised, allowing the user to again take advantage of its spiraling motion. When Albert and Henry Goodell developed a cobbler's rasp in 1892, it became the last tool that they would patent as partners in Goodell Brothers. Their sons were approaching manhood and interested in going into the tool business. Assuming that each would marry, the modest operation would need to support four families, and as anyone familiar with family businesses moving into the second generation can attest, inter-family politics were certain to become complex. Albert Goodell sold his shares in Goodell Brothers in 1892, and with plans for a new bit brace in his pocket, moved on to Worcester, Massachusetts, to start another business with his son Frederick.

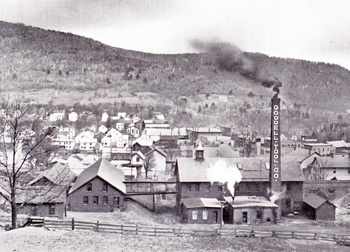

When Albert Goodell left the Goodell Brothers Company, Dexter W. Goodell, the brother who had advised him on his first patent, joined Henry Goodell as partner in the firm. The business moved to a new shop in Greenfield. Located on Wells Street, the company occupied a factory built for $2,000 by A. A. Alexander for the purpose of luring the Goodell Brothers operation to the city.(4) Dexter W. Goodell was every bit as talented as his brothers. A skilled patternmaker, he had gone to work for the Florence Sewing Machine Company in the 1860s, remaining with the company and its successor, the Florence Machine Company, for nearly three decades. During his long and productive career, D. W. Goodell registered at least fourteen patents for inventions that ranged from a faucet, to sewing machine components, to improvements in oil-burning stoves. Dexter Goodell did not stay with Goodell Brothers for long—he sold his interest in July 1895 when William M. Pratt, a salesman for local hardware manufacturer Wells Brothers & Company. As a result of his investment, Pratt became the Goodell Brothers Company's treasurer and general manager. D. W. Goodell became a manufacturer of nail pullers—underwriting the production of a nail puller patented by Charles A. Maynard of Springfield, Massachusetts, on August 24, 1897. Dexter Goodell monitored his investment from his home in Greenfield until 1898 when he sold his interest. He passed away 1901.(5)

The Goodell Brothers operation was neither large nor exceptionally successful. The number of employees in the factory is reported as having been between sixteen and twenty-four, and Henry Goodell served as owner, manager, master mechanic, tool sharpener, and machine setup person. Annual sales were in the vicinity of $30,000. The factory consisted of a single two-story brick building—100 feet by thirty feet—equipped with a boiler that provided heat in the winter and the energy required to run the twenty-five horsepower engine powering the belts that drove the shop’s machinery. Since there was no foundry, castings were purchased from outside suppliers, transported from the local rail depot to the plant by two-horse wagon, and machined on-site.(6) Prior to 1896, the company published no catalog and distributed its tools through other manufacturers. The very first Goodell Brothers No. 1 push drills had been sold by the Millers Falls Company. That arrangement was short-lived; the H. H. Mayhew Company of Shelburne Falls distributed most of the Goodell Brothers products—an agreement that lasted until the first catalog came out.(7)

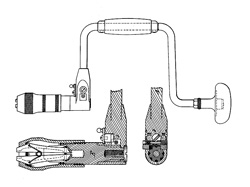

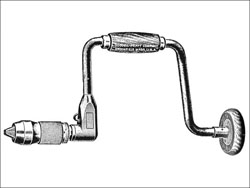

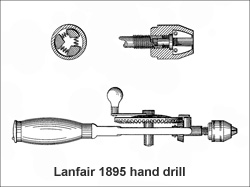

For all of Henry Goodell's talents, he was not a prolific inventor, and although his brother Dexter had invested in the operation, he appears not to have taken an active role in product development. If the business were to grow, attention to enlarging its product line was required. A solution to the problem appeared in the form of Herbert D. Lanfair, the thirty-four-year-old son of the Goodells' sister Anne. Lanfair worked for the nearby Millers Falls Company and had recently designed a bench stop, power hack saw, and an innovative four-faced spokeshave for the firm.(8) He was recruited for the family business, relocated to Greenfield, and in 1895 patented a well-designed hand drill that he assigned to the Goodell Brothers Company. The drill featured a three-jaw chuck and appeared at a time when two-jaw hand drills were losing favor due to their limited ability to securely hold all but the smallest round-shanked bits. Although the patent (United States Letters Patent No. 544,411) also covered such features as an outboard rider to control drive gear wobble and a method for attaching a bit storage magazine to a drill frame, the tool's chuck was far and away its most valuable feature. Lanfair's 1895 chuck became the standard for the impressive line of Goodell Brothers and Goodell-Pratt hand drills that followed.

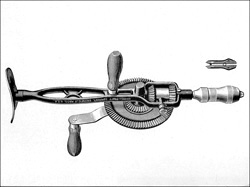

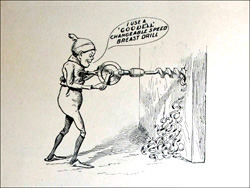

Although Albert D. Goodell was no longer with the Goodell Brothers Company, he teamed up with Henry in 1896 on a project to design a two-speed breast drill. It would be their last collaborative patent project.(9) At the time, the usual method for changing the speed on a breast drill involved removing the drive gear from the frame and repositioning it to allow it to contact with a second pinion. The brothers developed a clutch and shifter mechanism that enabled a user to change speeds by simply rotating a small adjuster nut, an improvement that not only eliminated the manual repositioning of the drive gear but allowed speed changes with the bit still engaged in the workpiece. The 1897 Goodell Brothers catalog included a promotion for the drill that featured an illustration of two elves—one happily using the new breast drill and the other struggling miserably with a competitor's product. Although the elves were shelved after a single outing, they are notable in that they were the forerunners of Mr. Punch, the hideously ugly mascot introduced about 1915 by Goodell-Pratt, the successor to the Goodell Brothers Company.

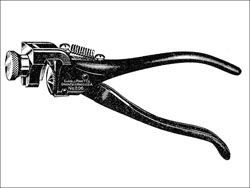

In 1897, Henry Goodell and Henry D. Lanfair patented a tool that the company referred to as a reversible automatic interchangeable screw-driver. (Oddly, the name didn't catch on.) The versatile tool's spiraling features could be adjusted to allow it to both drive and draw screws. The new tool was needed; managers of small-component assembly operations had become increasingly interested in reversible screwdrivers since James W. Jones and F. A. Howard patented a bi-directional spiral screwdriver in 1892. When Jones improved the patent in 1895, other hardware producers, such as the North Brothers Manufacturing Company of Philadelphia, took notice and began to develop successful variations of the tool.(10)  The Jones/Howard and North Brothers screwdrivers utilized a double spiral cut into a single rod to effect the wondrous change of direction. Goodell and Lanfair used a pair of telescoping spirals that were controlled by a pair of lockable nuts to do the same. As other inventive tool manufacturers began to find ways of getting around the early patents, the single-rod solution came to dominate the marketplace. Though its design was well outside the mainstream, the Goodell/Lanfair telescoping screwdriver enjoyed strong sales. When the successor to Goodell Brothers, the Goodell-Pratt Company, began adding single-rod reversible screwdrivers to its lineup, it continued to offer the telescoping tool. Production of the Lanfair/Goodell reversible screwdriver ceased in 1930.(11)

The Jones/Howard and North Brothers screwdrivers utilized a double spiral cut into a single rod to effect the wondrous change of direction. Goodell and Lanfair used a pair of telescoping spirals that were controlled by a pair of lockable nuts to do the same. As other inventive tool manufacturers began to find ways of getting around the early patents, the single-rod solution came to dominate the marketplace. Though its design was well outside the mainstream, the Goodell/Lanfair telescoping screwdriver enjoyed strong sales. When the successor to Goodell Brothers, the Goodell-Pratt Company, began adding single-rod reversible screwdrivers to its lineup, it continued to offer the telescoping tool. Production of the Lanfair/Goodell reversible screwdriver ceased in 1930.(11)

When William M. Pratt bought his fifty percent stake in Goodell Brothers in 1895, the business was incorporated, and the dynamics of the enterprise began to change. As a former sales agent for the Wells Brothers & Company, Pratt was far more cognizant of the need for an aggressive marketing operation than the Goodells had been. The Goodell Brothers Company began publishing a catalog and inking deals with major hardware wholesalers. Sales increased dramatically. No longer the family operation that it once had been, the opportunities for Henry Goodell's son Harry to take a leadership role in the business were becoming fewer.

On January 1, 1897, the elder Goodell and his son sold their interest in the Goodell Brothers Company. They did well by the sale. The Boston Sunday Globe noted that Henry E. Goodell left the business with a "moderate fortune."(12) Henry L. Pratt chose Frank Taft, former supervisor of the Brattleboro power plant, to serve as superintendent of the Goodell Brothers Company. Henry Goodell stayed on for three weeks to effect a smooth transition. In February 1899, the directors of the Goodell Brothers Company renamed the business, and the operation became the Goodell-Pratt Company.

Goodell, Son & Company

Before the month was out, Goodell, his son Harry, and his nephew Herbert D. Lanfair were at work on yet another venture—a business named Goodell, Son & Company located in the Pond building on Greenfield's Miles Street. Goodell, Son & Company was a small operation, powering its equipment with electricity and seeking to carve a niche in the hacksaw market.(13) The choice was a logical one given that the Goodell Brothers patents had been sold along with the company and that Lanfair was experienced with metal-cutting saws. Though he had been issued United States Letters Patent No. 466,929 for his work on the Millers Falls Company's power hacksaw, Lanfair considered that his major contribution to hacksaw development lay in solving the problem of frequent breakage of highly tempered hacksaw blades. Lanfair noticed that cutting on the push stroke put substantial stress on the thin blades while cutting on the pull stroke was kinder to them. Though not a patentable feature, it was an observation that had allowed the Millers Falls Company to move forward with its successful power hacksaw. Lanfair claimed to have made a small fortune from this discovery—an assertion that was likely to have been on the colorful side.(14)

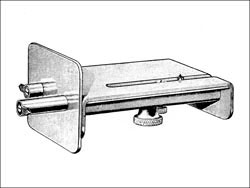

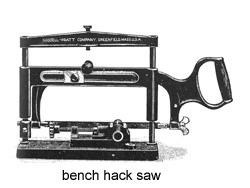

Just how soon Goodell, Son & Company began to manufacture tools is hard to determine. The operation may have served as a general-purpose machine shop until such time as products were developed. In August 1898, Herbert Lanfair and Henry Goodell applied for a patent for a bench hacksaw—a carriage-mounted saw suspended over a machinist's vise that could be rotated to allow for cutting a piece of stock at an angle. The stability of the carriage mount improved the efficiency of a worker's saw strokes while the vise made for easy retention of such difficult-to-hold pieces as plumbers' stock. Save for the fact that the target stock was rotated, rather than the saw, the use of the device was similar to that of a miter box. Goodell, Son & Company folded before the patent for the bench hacksaw was awarded. Henry Goodell's son Harry was suffering from consumption (tuberculosis), and the environment within the shop was not conducive to his continued health. The operation was sold to Goodell Brothers Company in September 1898, and the new owners began manufacturing the bench hack saw. Two months after the sale, Harry Gaines Goodell and his father Henry purchased the store of Lester A. Luey and went into partnership in the retail grocery business. Their partnership lasted about a year, but Harry's condition worsened. He died of consumption in May of 1900, a few days short of his twenty-sixth birthday. (15)

With the sale of Goodell, Son & Company in 1898, Herbert D. Lanfair returned to employment with the Goodell Brothers. Just how long Lanfair stayed with the company remains unknown. According to William F. Hough, when Lanfair's association with the various Goodell companies ended, “he drifted to Springfield and New Haven, always in the hack business.”(16) His time in New Haven was marked by a stint with saw blade manufacturer Henry G. Thompson & Son (ca. 1908-1909). He eventually moved on to Southern California.

Henry E. Goodell and the Goodell Manufacturing Company

In April of 1899, the month before his son's untimely death, Henry E. Goodell became the first president of the Greenfield Machine Company. Greenfield Machine’s primary product was the Universal Grinder, a device for sharpening machine tools and finishing small parts. Originally manufactured and marketed by Wells Brothers & Company, interest in the Universal Grinder was such that additional capital and increased square footage had become the order of the day. A spin-off (Greenfield Machine) was created; Henry Goodell invested and became president and plant superintendent. The new company took up space in what was known as "the Green River Shop," a location that had served as the site of a number of businesses including an earlier, and much smaller, Wells Brothers operation. Henry Goodell remained with the Greenfield Machine Company for less than a year. He cited ill health when he resigned from his superintendent's position in November 1900. The following month he resigned from the board, selling his interest in the company to Edward F. Smith who became the operation's new president. Given that Goodell would be actively engaged in tool manufacture until 1916, it is reasonable to assume that his sudden departure from Greenfield Tool was a result of grief over his son's death.(17)

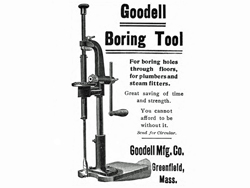

In August 1902, Henry E. Goodell went into business with his son-in-law, Perley E. Fay, and his brother-in-law, Fred A. Gaines. The men formed the Goodell Manufacturing Company, a corporation for the production of hardware specialties in which Goodell served as company president, Fay as treasurer, and Gaines as clerk. Construction soon began on a modest one-story building measuring 100 feet by forty feet with a forty-by-forty basement. The new factory was located on Greenfield's West Main Street.(18) Among the earliest tools manufactured at the plant were the Goodell Boring Tool, a cutoff tool for small-diameter round stock, and a self-centering punch. The Goodell Boring Tool was a specialized device designed for electricians and steamfitters who worked in environments where it was necessary to bore a large number of holes in a wooden floor within a short period of time—a situation encountered by contractors constructing apartment blocks or retrofitting older structures for electricity or steam heat. Fitted with a Clark expansive bit with two cutters, the tool could be easily adjusted to bore holes of different sizes. Goodell's boring tool may have been too specialized; it disappeared from the market within several years of its introduction.(19) Goodell Manufacturing's bell-type self-centering punch, designed for marking the centers on both square and round stock, was more successful and eventually sold by the Goodell-Pratt Company.

In his seminal article "Sorting out the Goodell Companies," Kenneth Cope writes that the Goodell-Pratt Company became part owner of the Goodell Manufacturing Company in 1903 and sole distributor of its tools.(20) Certainly the distribution arrangement belongs to the latter part of Goodell Manufacturing's history. For its first fourteen years, the company published its own circulars and price lists, and advertisements for its products appeared in trade journals directing readers to the company's Main Street address. The business's best-selling tools did not appear in Goodell-Pratt Company catalogs until 1917, the year after Henry Goodell retired from an active role in the business.

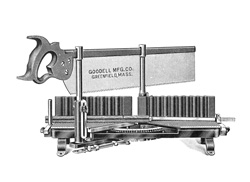

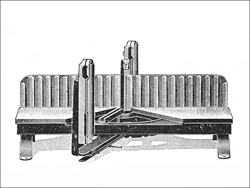

The Goodell Mfg. Company's all-steel miter box, patented by Henry E. Goodell in 1904, was touted for the quality of its construction and its resistance to breakage. As anyone who has given a cast iron miter box hard usage might attest, careless transportation and setup can result in the destruction of its more delicate parts—especially the legs that support the table. The steel components of Goodell's miter box were far more durable. A premium tool so popular that it was still marketed when the Goodell-Pratt Company was absorbed by the Millers Falls Company, the Goodell All-Steel Miter Box—now identified as a Millers Falls product—was sold until the latter 1940s when a redesign eliminated many of its distinctive features. Goodell Manufacturing brought out a second, cheaper miter box in 1910 when Henry Goodell was issued United States Letters Patent No. 978,576 for an iron miter box equipped with saw guides adjustable for blades of various thicknesses. This later tool was marketed as the Greenfield Miter Box, and it, too, was picked up by the Goodell-Pratt Company in 1917. Shortly afterward, Goodell-Pratt eliminated the Greenfield designation and renamed the box the Model 1000. The company dropped the Model 1000 from the lineup between 1928 and 1930, replacing it with another inexpensive miter box.

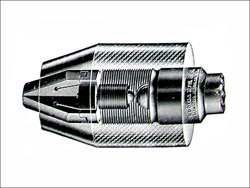

Goodell Manufacturing's Greenfield Drill Chuck, in production by 1912 and added to the Goodell-Pratt catalog in 1917, was a machinist's dream. With a one-piece shell, concealed threads, and double ball bearings, the chuck tightened well with minimal pressure, and its jaws centered easily and accurately. In some ways, the quality of the chuck was a reflection of the quality of the operation as a whole. The Goodell Manufacturing Company made good products and was known as a good place to work. Turnover was low, its machinists were valued, and the business was proud of its status as a unionized factory. Though a small enterprise, employees worked nine-hour days, received time and a half for overtime, and double time for Sundays. Its agreement with the International Association of Machinists required a minimum of one apprentice for the factory or one for every five journeymen. A typical apprenticeship lasted four years, after which the employee achieved journeyman pay status. The shop employed only union members as skilled workers.(21) At the time, the Goodell Manufacturing Company was considered a model of progressive business practices.

Henry E. Goodell died of pneumonia on February 23, 1923, and William M. Pratt, the president of the Goodell-Pratt Company, assumed the presidency of Goodell Manufacturing. In March 1930, the Goodell-Pratt Company purchased the remainder of the Goodell Manufacturing Company from Henry Goodell's son-in-law, Perley E. Fay, and moved its equipment to the main Goodell-Pratt plant on Wells Street.

Albert D. Goodell and the Goodell Tool Company

When Albert D. Goodell sold his share of the Goodell Brothers Company in 1892, he did so to go into business with his son Frederick. The men relocated to Worcester, Massachusetts, where they went into business as the Goodell Tool Company. Little is known about the Worcester operation since Goodell Tool was located there for just a year. The patent for the bit brace that Albert designed during his last months at Goodell Brothers was finalized during this time, so it is safe to assume the Goodell Tool Company was involved in getting the tool's production up and running. The bit brace featured close-fitting pawls that kept dirt out of its ratchet, a handy lever-style ratchet adjuster, and clothespin-spring self-opening jaws.(22)

Albert and Frederick Goodell relocated to Shelburne Falls in 1893 and rented space in the factory of local hardware manufacturer H. H. Mayhew Company. Mayhew was handling sales for the Goodell Brothers Company and did the same for Goodell Tool. In 1896, the Goodell Brothers Company terminated its sales arrangement with H. H. Mayhew and began to market its own tools. The Goodell Tool Company distributed its tools through both firms.

Among the tools sold by the Goodell Brothers Company was an interesting variant of Albert Goodell's 1892 brace. Referred to as the Goodell-Hay Ratchet Brace, the tool featured a quick-action chuck that had been patented by Francis. M. Hay of Erie, Pennsylvania.(23) The chuck required just a half turn to secure or loosen a bit, and coupled with Albert Goodell's lever-type ratchet mechanism, the premium-quality Goodell-Hay brace made for a nice addition to any worker's toolbox. Save for the chuck, the Goodell-Hay brace was identical to those produced by the Goodell Tool Company. A likely explanation for the brace's appearance in Goodell Brothers catalogs is that Goodell Brothers owned the rights to Hay's patent and Goodell Tool manufactured it for them under contract.

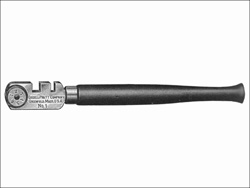

On December 18, 1894, the Patent Office issued United States Letters Patent No. 531,114 to Albert D. Goodell for a combined hinge gauge and square. Known by tradesmen as a butt gauge, the tool was of a type commonly used to scribe lines on the edges of doors and their casings before chiseling the recesses for the hinges. Hinges installed in this manner are referred to as butt hinges because they are fastened on the edge of the door—which butts against the casing (as opposed to face-mounted hinges such as strap hinges, clamshell hinges, or butterfly hinges). Featuring a rugged sheet metal body, the gauge was compact, lightweight, and easy to adjust. It also functioned as a try square for marking the ends of mortises. Goodell's gauge was so well designed that the Millers Falls Company marketed it as the No. 227 Combination Butt Gauge until the early 1960s.

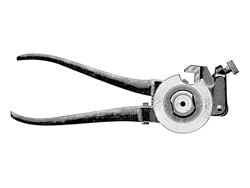

Between the end of 1894 and the beginning of 1906, Albert Goodell patented five tool designs. One of the patents, for a miter box, was assigned to the Langdon Mitre Box Company. Another, co-patented with his brother Henry in 1896, was for a breast drill that was to be sold by the Goodell Brothers Company rather than Albert's Goodell Tool Company. It is hard to determine whether all of the remaining three patents were ever put into production, but the last of the five, a patent for a turret-head glass cutter, would prove very successful. Goodell's design featured six cutting wheels which were mounted on a turret. When one cutting wheel dulled, the turret could be rotated so that another wheel could take its place. Goodell Tool manufactured two versions of the cutter: the No. 1, which had a wooden handle; the No. 2, which had a metallic body with an integral putty knife on the end opposite the head. The Goodell Tool Company also manufactured a glass tube cutter that proved especially useful in laboratory environments. Earlier examples of the tube cutter were marked Goodell Tool Co.; later production was marked Goodell-Pratt.

In 1904, the Goodell Tool Company purchased the peg shop of J. R. Foster, a structure located on the Buckland side of the Deerfield River. The shop had an interesting history. Constructed in 1893 by Jacob R. Foster to make pegs used to fasten the soles of cheap shoes to their uppers, it had been sited at Shelburne Falls to take advantage of an apparently inexhaustible supply of the high-grade white birch best suited to peg manufacture. Unfortunately for Foster, the birch, considered adequate to support a century’s worth of production, was gone in five years. The peg shop closed, the equipment was moved to Plymouth, New Hampshire, and the building became home to the American Metal Casket Company. The casket company relocated in 1902, and the building stood vacant prior to its occupancy by the Goodell Tool Company.(24)

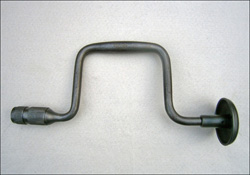

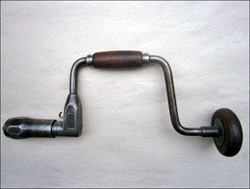

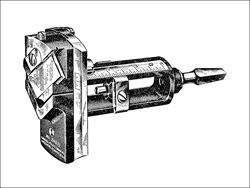

A year after the move to the former peg shop, the United States Patent Office awarded United States Letters Patent No. 789,536 to Albert D. Goodell for a corner brace with an appearance unlike any other on the market. (Brace pictured above.) Marketed as the Universal Corner Brace, the tool was compact, fitting easily into a toolbox when folded in on itself. In addition to its rotating handle, the brace featured a steadying handle that could be fixed in any one of eight pre-set positions—a detail that allowed a worker great flexibility in maneuvering the tool into place. While the brace sold fairly well, it was not without a design flaw. The tool's compact design meant that the arm of the hand gripping the steadying handle was best kept parallel to the chuck while the tool was in use. If incorrectly positioned, the user's forearm interfered with the complete rotation of the crank.

When the Goodell Tool Company was incorporated in 1907, one-half of its stock passed to the Goodell-Pratt Company. After the incorporation, Albert D. Goodell served as Goodell Tool Company president; Francis R. Pratt (the father of William M. Pratt) served as vice president; and Frederick Goodell (Albert Goodell’s son) was employed as its clerk.(25) The Goodell Tool Company soon moved its tool distribution to the Goodell-Pratt Company. Albert Goodell would patent an additional three tools for the corporation in 1910 and 1911—a bench hook, a saw set, and a hollow auger. Typical of A. D. Goodell's efforts, the tools were well-designed and sold well. The hollow auger was produced in two formats—as an attachment that could be chucked into a standard bit brace and as a bit brace featuring an integral hollow auger.(26)

Goodell Tool employed at least some children, a situation not unusual in the era before the enactment of laws prohibiting child labor. In 1895, thirteen-year-old Thomas O’Neil took a job at the Goodell Tool Company factory. It was the beginning of a career that would span fifty-one years, including three decades at the Goodell Tool plant in Shelburne Falls and twenty-plus years at the Goodell-Pratt site in Greenfield. At the turn of the century, employees of the Goodell Tool Company worked fifty-five to sixty-hour weeks, and those at the bottom of the pay scale earned just five cents an hour. Starting with the firm at an early age had its advantages; Thomas O’Neil was a company foreman by age twenty. His abilities were such that he was soon given responsibility for doing all the hiring and firing at the plant. At its peak, the Goodell Tool Company employed seventy-five men, and when the operation was folded into the Goodell-Pratt operation in Greenfield in 1925, O’Neil and twenty others took jobs at the new location.(27)

Suffering from a heart condition, Albert D. Goodell spent his final years in semi-retirement. He died at his home on May 1, 1915, while reading the evening mail.(28) Frederick A. Goodell remained in Shelburne Falls and set up a small tool shop on Water Street for the production of glass cutters and doing general machinist-type work. In poor health, he took his life with a .32 caliber rifle in the basement of his business on April 9, 1929.(29)

Albert D. Goodell and Henry E. Goodell Patents

| Patent Number | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 79,825 | July 14, 1868 | A. D. Goodell, bit stock |

| 139,667 | June 10, 1873 | A. D. Goodell, bit stock, assigned to Millers Falls Mfg. Company |

| 141,345 | July 29, 1873 | A. D. Goodell, bit stock, assigned to Millers Falls Mfg. Company |

| 220,732 | October 21, 1879 | A. D. Goodell, miter box, co-patentee D. C. Rogers, assigned to Langdon Mitre Box Co. |

| 222,820 | December 23, 1879 | A. D. Goodell, machine for re-cutting wagon axles |

| 228,810 | June 15, 1880 | A. D. Goodell, ratchet bit brace, assigned to Millers Falls Company |

| 228,811 | June 15, 1880 | A. D. Goodell, bit brace, assigned to Millers Falls Company |

| 293,651 | February 19, 1884 | A. D. Goodell, spokeshave, assigned to Millers Falls Company |

| 332,391 | December 15, 1885 | A. D. Goodell, scroll sawing machine, assigned to Millers Falls Company |

| 374,593 | December 13, 1887 | A. D. Goodell, drill chuck, assigned to Millers Falls Company |

| 374,594 | December 13, 1887 | A. D. Goodell, drill chuck, assigned to Millers Falls Company |

| 391,242 | October 16, 1888 | A. D. Goodell, spirit level, assigned to Millers Falls Company |

| 432,729 | July 2, 1890 | A. D. Goodell, screwdriver, co-patentee H. E. Goodell |

| 463,506 | November 17, 1891 | A. D. Goodell, automatic screwdriver, co-patentee Henry E. Goodell |

| 463,507 | November 17, 1891 | A. D. Goodell, drilling tool, co-patentee H. E. Goodell |

| 472,259 | April 5, 1892 | A. D. Goodell, shoe float or rasp, co-patentee H. E. Goodell |

| 488,691 | December 27, 1892 | A. D. Goodell, bit brace |

| 531,114 | December 18, 1894 | A. D. Goodell, combined hinge gauge and square (butt gauge) |

| 544,092 | August 6, 1895 | A. D. Goodell, miter box, assigned to Langdon Mitre Box Company |

| 557,200 | March 31, 1896 | A. D. Goodell, glass cutter |

| 557,328 | March 31, 1896 | A. D. Goodell, breast drill, co-patentee H. E. Goodell |

| 563,372 | July 7, 1896 | A. D. Goodell, tool chuck for bit stock |

| 566,905 | September 1, 1896 | A. D. Goodell, drill chuck |

| 591,097 | October 5, 1897 | H. E. Goodell, reversible automatic screwdriver, co-patentee H. D. Lanfair, assigned to Goodell Bros. |

| 627,183 | June 20, 1899 | H. E. Goodell, bench hacksaw, co-patentee H. D. Lanfair, assigned to Goodell, Son & Co. |

| 751,908 | February 9, 1904 | H. E. Goodell, miter box, assigned to Goodell Manufacturing Company |

| 789,536 | May 9, 1905 | A. D. Goodell, corner brace |

| 862,069 | July 30, 1907 | H. E. Goodell, breast drill |

| 974,482 | November 10, 1910 | A. D. Goodell, bench stop, assigned to Goodell Tool Company |

| 978,576 | December 13, 1910 | H. E. Goodell, miter box |

| 984,478 | February 14, 1911 | A. D. Goodell, saw setting device, assigned to Goodell Tool Company |

| 1,010,894 | December 5, 1911 | A. D. Goodell, device for shoulders on wooden spokes |

Illustration credits

- A. D. Goodell: Framed and labeled portrait at Shelburne Historical Society, Shelburne Falls, Mass. This photograph of the original is copyright of the author.

- Goodell 1868 brace: Author's photo.

- 1868 brace cross section: United States Letters Patent No. 79,825, (July 14, 1868).

- Dexter Goodell brace: United States Letters Patent No. 51,173, (Nov. 28, 1865).

- H. E. Goodell: Biographical Review: Sketches of the Leading Citizens of Franklin County, Massachusetts. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Co., 1895.

- 1890 push drill, 1890/91 screwdriver: Author's photos.

- 1892 bit brace: United States Letters Patent No. 488,691, (December 27, 1892).

- 1895 Lanfair drill: United States Letters Patent No. 544,411, (August 13, 1895).

- Goodell breast drill: Tools Manufactured by the Goodell-Pratt Company: Catalogue No. 6. Greenfield, Mass.: Goodell-Pratt Co., 1903.

- Goodell elves: Goodell Brothers Company, Manufacturers of Mechanics Tools & Specialties: No. 2. Greenfield, Mass.: Goodell Brothers Co., 1897. Courtesy of the Museum of Our Industrial Heritage, Greenfield, Mass.

- Telescoping screwdriver: Author's photo.

- Bench hack saw: Tools Manufactured by Goodell-Pratt Company: Catalogue No. 7. Greenfield, Mass.: Goodell-Pratt Co., 1905.

- Goodell boring tool: The Metal Worker, Plumber, and Steam Fitter. v. 63, no. 1, July 1, 1905.

- Cut-off tool and centering punch: Tool Book Number 13. Greenfield, Mass.: Goodell-Pratt Company, 1917.

- Goodell Mfg. Co. factory: Western New England. v. 2, no. 6, July 1912.

- All-steel miter box and Greenfield Miter Box: Tool Book Number 13. Greenfield, Mass.: Goodell-Pratt Company, 1917.

- Greenfield Drill Chuck: Western New England. v. 2, no. 6, July 1912.

- Goodell Tool Co. factory: Western New England. v. 2, no. 4, April 1912.

- Goodell Tool Co. ratchet brace: Author's photo.

- Goodell-Hay Ratchet Brace: Complete Catalog Number 16. Greenfield, Mass.: Goodell-Pratt Company, 1926.

- Combination hinge gauge: Tools Manufactured by Goodell-Pratt Company: Catalogue No. 7. Greenfield: Goodell-Pratt Company, 1905.

- Turret head glass cutter: Tool Book Number 13. Greenfield, Mass.: Goodell-Pratt Company, 1917.

- Glass tube cutter and Universal Corner Brace: Author's photos.

- Bench stop, saw set, hollow auger: Complete Catalog Number 15. Greenfield, Mass.: Goodell-Pratt Company, 1923.

- Frederick A. Goodell: Framed and labeled portrait at Shelburne Historical Society, Shelburne Falls, Mass. This photograph of the original is copyright of the author.

References

- History of the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts: with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of its Men and Prominent Pioneers. Volume II. Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1879. p. 701; "Henry E. Goodell." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) February 24, 1893.

- United States Letters Patent No. 51,173, (Nov. 28, 1865).

- [Untitled]. Springfield Republican (Springfield, Mass.) April 6, 1870. p. 8.

- Margo P. Jones. Town of Greenfield Historical Survey & Planning Grant: Final Report. Greenfield, Mass.: Office of Pierre A. Belhumeur, 1984.

- Greenfield Recorder (Greenfield, Mass.). October 30, 1901. p. 4; United States Letters Patent No. 27,571.

- Biographical Review: Sketches of the Leading Citizens of Franklin County, Massachusetts. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company, 1895. p. 326-327; information on Goodell Brothers shop: William F. Hough. “Over 40 years ago.” Dyno-mite (October 1942). p. 8.

- Arrangement with Mayhew Company: Mechanics’ Tools and Specialties: No. 1. Greenfield, Mass.: Goodell Brothers Co., 1896.

- The bench stop: United States Letters Patent No. 438,890, (October 21, 1890); the power hack saw: United States Letters Patent No. 466,929, (January. 12, 1892); the spokeshave: United States Letters Patent No. 508,427, (November 14, 1893).

- United States Letters Patent No. 557,328, (March 31, 1896).

- Clifford F. Fales. "The Spiral Screwdrivers of Isaac Allard, F. A. Howard and J. W. Jones." The Gristmill. No. 67 (June 1992). p.10-14.

- The Goodell/Lanfair screwdriver: United States Letters Patent No. 591,097, (October 5, 1897).

- "Brattleboro." Boston Sunday Globe (Boston, Mass). January 3, 1897. p. 2.

- "The Goodells Sell Their Interest in the Manufacturing Corporation Bearing Their Name." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) January 2, 1897. p. 6.; North Adams Daily Transcript (North Adams, Mass.) January 27, 1897.

- "Simple Idea Wins Fortune." Hayward Daily Review (Hayward, Calif.) December 3, 1931. p. 2.

- "The Luey Store Sold to Harry Goodell—Prospect of a New Wholesale Grocery House." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) November 5, 1898. p. 6; obituaries: W. C. Townsend. "Goodell." Zion’s Herald, v. 78, no. 25 (June 20, 1900). p. 798; "Death of Harry G. Goodell." Greenfield Recorder (Greenfield, Mass.) May 9, 1900. p. 3.

- William F. Hough. “Over 40 years ago.” Dyno-mite (October 1942). p. 8.

- Greenfield Manufacturing Company: "A New Manufacturing Company." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) April 4, 1899, p. 6; "Greenfield Items." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) November 3, 1900, p.4; "Greenfield Items." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield Mass.) December 8, 1900, p. 4.

- "Greenfield Items." Gazette and Courier(Greenfield, Mass.) August 23, 1902, p. 6.

- United States Letters Patent No. 719,934, (February 3, 1903). Calvin L. Butler was awarded some thirteen patents—about half were for improvements to cutlery.

- Kenneth Cope. “Sorting out the Goodell Companies.” Chronicle of the Early American Industries Association, v. 45, no. 4 (December 1992). p. 115.

- "Agreement between Goodell Manufacturing Company and the International Association of Machinists." Machinists Monthly Journal. v. 16, no. 12 (December 1904). p. 1067-1068.

- United States Letters Patent No. 488,691, (December 27, 1892).

- United States Letters Patent No. 526,314, (September 9, 1894).

- Fannie Shaw Kendrick. The History of Buckland. Buckland, Mass.: Town of Buckland, 1937. p. 252-253.

- The bench stop: United States Letters Patent No. 974,482; the saw set: United States Letters Patent No. 984,478; the hollow auger: United States Letters Patent No. 1,010,894.

- Kenneth Cope. “Sorting out the Goodell Companies.” Chronicle of the Early American Industries Association, v. 45, no. 4 (December 1992). p. 115.

- “51 years.” Dyno-mite, (Aug. 1946). p. 15.

- "Albert D. Goodell." Shelburne Falls Messenger (Shelburne Falls, Mass.) May 7, 1915.

- "Fred A. Goodell Commits Suicide." Springfield Republican (Springfield, Mass.) April 10, 1929.