L. Garth Huxtable: Industrial Designer for Millers Falls

A revision of the article appearing in the June 2002 issue of The Gristmill: the Journal of the Mid-West Tools Collectors Association.

On November 24, 1972, industrial designer Garth Huxtable wrote to Leonard C. Pratt, a partner in many of his design projects, on learning that Pratt was no longer serving as Vice President for Development Engineering at the Millers Falls Company.(1)

Dear Len,

Rob’s recent letter reported that you and Millers Falls had recently parted company. I was about to send my regrets, as leaving a company after so many years is normally unsettling. But I think that congratulations are in order the way things seem to have developed. I think we all had Millers best years, and working with you was always a pleasure.

With our tools, over the years, it was always good to have engineering backup to keep from going too far out on a design limb, and, in spite of some mistakes, our batting average was pretty good.

Huxtable had learned of Pratt’s departure from his brother, Robert, an engineer responsible for the company’s hand tool development. The Manhattan-based industrial designer, writing from his Park Avenue apartment, had spent over twenty years designing tools for Millers Falls—many of them in cooperation with Pratt and his staff. He was well aware of the company’s growing ineffectiveness in the consumer hand tool market, a situation many attributed to a dearth of capital investment and lack of commitment to the operation by Ingersoll-Rand, the corporation that had purchased the firm in 1962. Cost-cutting measures had resulted in the elimination of Huxtable’s design services in 1970, a time when the mother factory in Millers Falls was shut down and operations were consolidated in nearby Greenfield.

Garth Huxtable’s career in design had begun in the early 1930s and spanned nearly four decades. The years in which he practiced his art were those in which independent industrial designers shaped the products enjoyed by the American consumer to a degree no longer widely appreciated. From the trains and planes he traveled in, to the chair she sat in, to the cup holding the morning coffee, Mr. and Mrs. America lived in an environment created, in large part, by a cadre of outside consultants that provided manufacturers with an understanding of the human factors and the art needed to create successful new products. It was inevitable that tool companies such as Stanley, Disston, and Millers Falls would make use of outside design services during the post-war era—the consulting designer arrangement had become a standard way in which products were developed.

The design era begins

When Henry Ford introduced the Model T in 1908, his new car was a luxury item selling for just under a thousand dollars. Thanks to the marvel of mass production, a short six years later a worker with $300 in his pocket could buy a spanking new “Tin Lizzie.” The techniques of manufacture had become so effective that it had become easy to oversupply the market with a product, and companies faced the novel problem of encouraging repeat sales before the life of an item had expired. Fortunately, human nature being what it is, consumers begin to seek out newer and better products once their basic wants are met. With the overwhelming abundance of material goods available in the 1920s, it was soon no longer enough just to own an item. Consumers began to demand quality in appearance and comfort in use on a scale not seen before.(2)

Although corporations excelled in engineering and production, they were not as equipped to understand the human factors that motivate customers to buy. Effective mass marketing required the sort of sophisticated advertising that moved beyond the simply informative to the attention-getting and psychological. Lacking the expertise to develop their promotional material, companies turned to independent agencies to provide them with know-how. At the same time, there was a growing belief within the advertising and applied arts communities that a product could be so well designed, in function and appearance, that it would help to create its own demand. While the design approach to marketing was not entirely new, in a mass production environment it had the potential to radically alter the quality of the objects of everyday life.

When products developed by practitioners of the design approach to the marketplace became wildly successful, manufacturers took notice, and the services of these individuals came into demand. As was the case with advertising, independent firms and consultants sprang up to provide manufacturers with an outlook, knowledge, and methodology the companies did not have. Most successful practitioners, in addition to having an artistic sensibility, were comfortable with new technologies and materials, advertising, drafting, and engineering. Products as diverse as kitchenware, radios, refrigerators, and steamships began to be developed through the new design process, and a new profession, that of industrial designer, was born.

Although the earliest documented use of an outside industrial designer by the Millers Falls Company can be traced to 1945, it is likely the practice began a decade earlier. A number of tools depicted in Catalog No. 42, published in 1938, would almost certainly have been products of the new design paradigm. The 400 series of Dyno-Mite electric drills stand out as clean, wonderfully integrated products, a far cry from earlier models—tools more aptly termed “collections of parts.” The catalog also introduced a series of hand tools equipped with “permaloid” handles and chrome, rather than nickel, plating. Though the new tools with their bright red transparent handles and gleaming surfaces were so traditional in form they would have earned an “F” in a design class. The obvious appeal to the marketplace and creative use of chrome and recently developed red plastic bear the fingerprints of an outside consultant. So too, the manufacturing process. Designers encouraged companies to look beyond their internal manufacturing capabilities to realize the possibilities inherent in new technologies. The tools’ permaloid components, made from Hercules Powder Company cellulose acetate, were subcontracted to the Worcester Moulding Plastics Company.

Early career

Leonard Garth Huxtable was born December 15, 1911, in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. When he was fourteen, his family moved to Fitchburg, Massachusetts. After completing high school, he relocated to Boston to study at the Massachusetts School of Art. There he became fascinated with the work going on in the new field of industrial design while attending presentations made by such pioneers as Walter Dorwin Teague, Henry Dreyfuss, and Joseph Sinel. Impressed with what they were doing and graduating with a degree in design in 1933, he moved to New York, to “look for worm,” as he put it, in the depths of the Great Depression.

After a stint in several advertising art studios, Huxtable got his first break as a design draftsman in the office of Norman Bel Geddes. Originally a theatrical designer, Geddes was a visionary and futurist whose popular, streamlined products defined industrial design for a generation of Americans. Three parts artist, two parts designer, and one part showman, the talented, if somewhat erratic, Geddes had as much to do with gaining public recognition for the fledgling industrial design profession as anyone. His office was a hotbed of streamlining, a technique that serves to create the impression that an object is in forward motion, would remain popular with American designers for nearly twenty years. The style became so pervasive that it was eventually applied to such entirely inappropriate objects as pencil sharpeners and fountain pens.(3)

Starting out at the princely sum of six dollars a week, Huxtable was one of a staff of twenty and served as design development draftsman for Revere Copper giftware, a variety of domestic appliances, and the interiors of Pan-American planes. The atmosphere in the office was chaotic, to say the least. Employees often lasted less than a month or two, and at one time, Huxtable was the only employee remaining on the job. Incredibly, less than a year after the young designer signed on, Geddes became preoccupied with projects for the theatre, and the office folded. Huxtable quickly snagged a position with Egmont Arens, another of the giants in the profession. He stayed for a little over a year, designing kitchen equipment for Hobart Manufacturing, weighing devices for Dayton Scales, and Higgins ink bottles until he was called back to Norman Bel Geddes and Co.

Shortly after his return, Huxtable was assigned to the design development team for a series of models that would be one of the office’s design triumphs—the General Motors Futurama at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. The fair proved to be a showcase for the greatest design of the era, and many consider the Futurama its crowning glory. The Futurama, a model portraying the cities, suburbs, towns, countryside, and superhighways of America in 1960, occupied 35,000 square feet and was built in 408 sections. Five hundred fifty-two gliding sound-chairs moved over and around the model as up to 28,000 persons per day listened to pre-recorded narratives describing marvels that many expected would occur in their lifetime.

Huxtable, much to his disappointment, was pulled from the Futurama project not long after the initial drawings were done. He was needed to make design drawings for the new Geddes offices in Rockefeller Center. The office project was followed by several other tasks for the fair—the Wilson Co. exhibit and, a pet project for the boss, a girlie show called the Crystal Lassies. In mid-1939, he left the firm and moved to Detroit to work first with the Albert Kahn office and then with General Motors. As part of GM’s internal design group, he did research and design for Frigidaire, Greyhound Bus, and a variety of automotive products.

But the pull of New York was strong, and in 1941, Garth Huxtable returned to the city to work with Benjamin Webster and noted designer Henry Dreyfuss. In a space of less than a year, he worked on such seemingly unrelated products as agricultural machinery, weighing scales, and fountain pens. The variety of his projects was not all that unusual, for it was a firmly held tenet of the profession that the principles of good design could be universally applied, and the measure of a practitioner was the ability to succeed at virtually any project. With the onset of the war, the development of consumer products came to a standstill, and the services of most designers became linked to the defense effort. Huxtable spent the war years as an assistant designer for Sperry Gyroscope Company where his major effort involved design work for the firm’s new defense plant at Lake Success, N. Y.

As the war began to wind down, opportunities for designers multiplied as companies, eager to meet pent-up consumer demand, raced to bring new products to the marketplace. Huxtable left Sperry Gyroscope to design laboratories and equipment for the Federal Telephone and Radio Corporation and then left Federal to go back to the independent firms. Designing for Benjamin Webster and then again for Geddes, Huxtable worked on projects as diverse as cigarette vending machines, railroad sleeper cars, and a proposed re-design of Ebbets Field.

Early work for Millers Falls

In the years following the Second World War, opportunities for design work were readily available and remuneration was good. So good that Huxtable decided to open his own office. He was well-positioned to make the move. In 1946, he had been accepted into the prestigious Society of Industrial Designers, a group comprised of the big names in the field and dedicated to the improvement of the profession. Well-connected and experienced in the architectural, packaging, machine, model, and exhibit areas of the profession, his move made sense. When Huxtable opened his office in 1948, the Millers Falls Company became one of his first clients.

The firm had come through the war years in good shape. Its electrical, hand, and precision tools had been in demand for the war effort, and despite difficulties in getting raw materials following the end of hostilities, the firm had good reason to be optimistic. During the war, full employment had wiped away the vestiges of the Depression. Although millions of workers earned steady wages in the defense industries, few consumer goods had been available for purchase. Personal savings accounts were swollen, and it was apparent there would be a housing boom with an attendant need for construction tools. In addition, workbenches in the garages and basements of the new homes would need to be stocked with handyman products as the former G. I.’s set up housekeeping. The era was bright with promise, and Millers Falls was determined to capture its share of the action.

Robert W. Huxtable, Garth Huxtable’s brother, was working as a draftsman for Millers Falls when the designer opened his office. Although he likely had little influence in the contracting process, he most certainly would have informed his brother of opportunities with the firm. Robert Huxtable's career at Millers Falls was one characterized by hard work and advancement. A believer in self-directed learning and the pursuit of educational opportunity, he studied to become an engineer and eventually was promoted to Chief Engineer & Supervisor of Quality Control for the hand tools area. He remained with the firm until retirement.

When Garth Huxtable began designing for the Millers Falls Company, the firm was already contracting for outside design work. Francesco Collura, like Huxtable a member of the Society of Industrial Designers, designed and patented a futuristic-looking hacksaw for the business in 1945.(4) The saw, featuring a lever-action blade tensioner, was fitted with red plastic handles and put into production in 1948, the year that another of Collura’s designs, a hand drill, was added to the line. The Collura used the company’s traditional No. 5 drill as a starting point for his design for his highly-stylized No. 104 hand drill.(5) Francesco Collura’s work for Millers Falls was not extensive; L. Garth Huxtable soon established himself as the company’s primary, and later, its sole, outside designer.

Garth Huxtable created the innovative No. 100 automatic push drill in 1948. The No. 100 was one of a pair of push drills developed by the designer at this time. The red-handled No. 100, with its top-loading magazine for bits, was designed for the Millers Falls line, and a blue-handled version, with its storage compartment at the lower end of the handle, was developed for the Sears line of Craftsman tools. Millers Falls was one of several manufacturers that supplied tools for the company’s Craftsman and Dunlop lines, and over the next dozen years or so Huxtable did design work for the tools. From glass cutters to circular saws, the giant retailer sold massive quantities of the Huxtable-designed tools via the pages of oversized catalogs found in millions of American homes.

The stunning tools of Francesco Collura and Garth Huxtable exerted a pull that proved hard for Robert Huxtable to resist. His drafting table was soon covered with designs for a bench plane with a red plastic handle and knob. Robert Huxtable’s plane was introduced in late 1949, and he was awarded United States Design Patent No. 159339 for it in 1950. A draftsman rather than designer, Robert Huxtable’s plane was a re-work of a tool developed by Samuel Oxhandler for the Sargent Company of New Haven, Connecticut, and was cited as such in the patent papers. The distinctive, forward-looking tools that the Millers Falls Company developed during this period have since been nicknamed the “Buck Rogers” tools because of the similarity of the bench planes to the ray guns carried by actors in science-fiction films of the 1940s and 50s.

The Buck Rogers tools exploited the possibilities inherent in die cast methodologies and post-war plastics. Die casting allows for the development of forms that are almost sculptural and which come from the mold needing a minimum of finishing. Although broken pieces cannot be welded and several common alloys do not retain paint well, die casting allows for the creation of complex, durable, and lightweight components that would otherwise be cost prohibitive. The tools’ plastic components were manufactured of Eastman’s tenite, a product much hyped in the design publications of the day. Available in a virtually unlimited choice of color, the material was advertised as being tough, impact resistant, dimensionally stable, and pleasant to touch. The synthetic had much to do with the tools’ striking appearance.

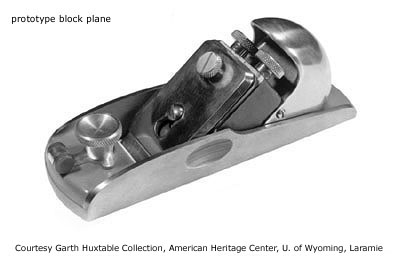

Almost as interesting as the tools produced from Garth Huxtable’s designs are his ideas for a block plane that never made it to the market. Designed to complement the firm’s No. 709 and 714 bench models, the tool didn’t get beyond the prototype phase. Surviving photos of the model show a handsome plane of standard pitch with an adjustable mouth and a dual-knob depth adjustment. The lever mechanism controlling the set of the mouth features a tenite tip similar to those used for the bench planes. Surviving renderings for similar highly-styled block planes illustrate some of the widely divergent concepts that were presented for consideration.

Garth Huxtable’s work for the Millers Falls Company was to remain a constant throughout his career. As his relationship with the firm developed, he was signed to an exclusive contract that guaranteed steady work in exchange for his promise not to design tools for any of the firm’s competitors. The contract contained no such prohibition on other projects, and Huxtable remained active in a number of areas. From 1949 to 1952, he served as a member of the United Nations Headquarters Planning Office and designed a number of furnishings for the new building. His contributions for the General Assembly were especially noteworthy and included the delegates’ desks and chairs, the lounge furniture, and the main information counter.

The 1950s

As his business developed, Huxtable asked his wife, Ada Louise, to join him in some of the office’s design projects. Her qualifications were excellent. A Phi Beta Kappa scholar and magna cum laude graduate of Hunter College, she held a degree in fine arts and shared his interest in architecture and design. While working as an assistant curator of architecture and design at New York’s prestigious Museum of Modern Art, she was awarded a Fulbright fellowship to study architecture and design in Italy. The couple’s mutual interests served to advance the careers of both. Her experiences in Italy and at the Museum of Modern Art served to establish connections that would ensure that her husband’s designs received the attention they merited. His connections in the workaday world of designers and architects were an asset to the writing she was doing while serving as a consultant in her husband’s office. Her knowledgeable, witty, and take-no-prisoners style would eventually establish her as a leading architectural historian and design critic.

L. Garth Huxtable received recognition for his tool designs in the mid-1950s. He had begun to exhibit some of his projects internationally, and, in 1954, he was awarded a silver medal at the prestigious Triennale di Milano. The Milan exhibition was the foremost event of its kind, and Huxtable was honored for the Millers Falls No. 1814, a die-cast aluminum electric drill with a gray hammer-tone enamel finish. He repeated his success at the 1957 Triennial, winning another silver medal with the Millers Falls Plane-R-File. The Plane-R-File, a stunningly beautiful surform tool, featured a rotatable handle that allowed for its use as either a file or a plane. The tool was considered such an outstanding example of styling married to functionality that it was added to the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. The idea of a replaceable-bladed rasp was not new to the Plane-R-File—similar products had existed in Britain for several years. Huxtable’s contribution lay in the rotating handle, blade locking mechanism and outstanding aesthetics.

The Plane-R-File designer received patent no. 2,839,817 on June 24, 1957. The patent covered the way in which the blade was fastened to the frame. The rotatable handle, while original for this type of tool, was considered too similar to other patents to be claimable. Design patent no. 182,026 covered the general appearance and was issued on February 4, 1958. Much to Huxtable’s dismay, the tool was soon copied, and he faulted the Millers Falls Company for not protecting the design patent. The company’s selection of the Tresa File Company of England as supplier of the abrading blades was another source of disappointment. In 1982, the designer was to recall:

For the invention of the ‘Plane-R-File’ abrading tool- I was said to receive one dollar and other considerations. This tool was not too successful as having lost the original blade to Stanley, Millers introduced the tool with an inferior blade. When it was time to reorder, a prohibitive price for the blade was asked. Stanley, Stanley of England and others wasted no time in copying the tool, and it proved very successful. Originally Stanley brought out two tools—a plane type and a file type. My invention combined the two—hence the name “Plane-R-File.” (6)

Although tool work took up much of his time, Huxtable remained active in projects that ranged from a baby carriage for the Thayer Company to a model town promoting S & H Green Stamps for Sperry & Hutchinson. Along the way, he developed an expertise in food service design and cutlery. A series of designs for Lunt Silversmiths of Greenfield in the mid-1950s led to an interest in flatware, glassware, and tableware that eventually resulted in several projects for the restaurant industry. The one for which Huxtable is most well known is one he undertook with his wife, the creation of glassware, china, and silver serving pieces for the famous Four Seasons Restaurant in Manhattan’s Seagram Building.

When Samuel Bronfman decided to build a headquarters for his Seagram distilling empire, he had little idea that he would be responsible for an architectural masterpiece. He offered the project to his 27-year-old daughter, Phyllis, after she had voiced strong objections to a design by an architect that he had already selected. Phyllis accepted the offer and found little trouble in deciding what she wanted. She chose Mies Van der Rohe, the famous German architect who had immigrated to the United States. He was hired for the job, and Philip Johnson, the head of the architecture and design department at the Museum of Modern Art, was chosen as his associate. When it was decided that the new building would house a first-class restaurant, Picasso was asked to do some sculpture for the eatery. He refused, but a painted stage backdrop he had previously executed was used. When Philip Johnson wanted Garth Huxtable to design the tableware, the answer was yes. Money was no object, and time was short. Garth and Ada Louise Huxtable, in a collaborative frenzy, designed over one hundred forty items for the restaurant. The results were so successful that eighteen of the pieces were selected for inclusion in the design collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

Success

As Ada Louise Huxtable’s writing career had begun to make increasing demands on her time, the Four Seasons project was the last of the couple’s major collaborative efforts. In 1963, she became the in-house architectural critic of the New York Times. A firm believer in the vitality of modern architecture, she was nonetheless horrified by what she saw as the senseless destruction of landmark buildings in the name of urban renewal. Passionate, discerning, and pointed, she took aim at targets ranging from sanitized history at Colonial Williamsburg to that most American of architectural horrors, the shopping mall. In 1970, Ada Louise Huxtable became the first person to be awarded a Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

The success of his designs for the Four Seasons cemented Garth Huxtable’s reputation in the food service industry. When Restaurant Associates, the firm operating the Four Seasons, was looking for table and serving ware for its ambitious new restaurant, La Fonda Del Sol, Huxtable became part of the design team with architect Alexander Girard. He completed a number of other projects for The Associates including the layout and interior design for the Newarker Coffee Shop and Restaurant at the Newark airport. When the Metropolitan Opera Association was looking for someone to design the Plaza Café at the Opera House at Lincoln Center, Huxtable was chosen. He was also selected to design the interior of the Tower Sky Lobbies Restaurant at the World Trade Center, a project he would find maddening because of the numerous construction delays. The work was never executed. Despite the number of food service projects coming his way, Huxtable’s work for Millers Falls continued unabated.

In 1960, the company introduced the first in a series of double-insulated power tools intended for home use. The product of an extremely close cooperation between Huxtable and the company’s engineering department, the new tool was the No. 1144 Safe-T-Drill. It featured a housing of Du Pont Zytel nylon resin and a plastic gear between the spindle and the motor that minimized the likelihood of electrical shock in the event of a power leak or cord failure. Safe, lightweight, comfortable to the touch in both hot and cold weather, and powerful for its size, the drill was well received. Huxtable’s choice of materials and the beauty of the housing played no small part in the tool’s success. Other double-insulated tools soon followed, and the company did well with its “shock-proof” tools for nearly a decade. Industrial design historian Arthur J. Pulos credits Huxtable with sounding the death knell for handheld power tools with polished aluminum housings.(7)

In 1960, the company introduced the first in a series of double-insulated power tools intended for home use. The product of an extremely close cooperation between Huxtable and the company’s engineering department, the new tool was the No. 1144 Safe-T-Drill. It featured a housing of Du Pont Zytel nylon resin and a plastic gear between the spindle and the motor that minimized the likelihood of electrical shock in the event of a power leak or cord failure. Safe, lightweight, comfortable to the touch in both hot and cold weather, and powerful for its size, the drill was well received. Huxtable’s choice of materials and the beauty of the housing played no small part in the tool’s success. Other double-insulated tools soon followed, and the company did well with its “shock-proof” tools for nearly a decade. Industrial design historian Arthur J. Pulos credits Huxtable with sounding the death knell for handheld power tools with polished aluminum housings.(7)

One of the first projects undertaken after Ingersoll-Rand purchased the Millers Falls Company in 1962 was the search for a new trademark. Management had become convinced that the triangular trademark that had served the company for over forty years was no longer effective. Considered by some to be the first of the mistakes the parent company would make with its Millers Falls operation, the questionable project was handed over to Garth Huxtable. The New York designer did a nice job coming up with a replacement—a square with rounded corners and the initials MF in the center. After some discussion, the words Millers Falls were added to the square, and the new logo was adopted in 1963. To the designer’s dismay, the division’s management opted to implement the new trademark in a piecemeal fashion. The changeover took four years to complete, and little was spent to promote the new mark. The lack of an easily identifiable trademark at a time when discount chains were making huge inroads into the hardware business did little to promote brand recognition. A decade after its introduction, after Huxtable had quit working with the company, a new circle and arrow trademark was adopted. A year later, Ingersoll-Rand combined its various small tool factories into an amalgam known as the Ingersoll-Rand Tool Group, and the new mark, too, was abandoned.

The end of an era

The closing of the Ervingside plant in Millers Falls and the relocation of all operations to Greenfield resulted in a lengthy moratorium on the development of new tools. The start of Huxtable’s new contract was put on hold for the duration, an event that marked the beginning of the end of the designer’s work for the company. By 1970, Garth Huxtable was no longer working with Millers Falls.

The era of the independent industrial designer was coming to a close. The pioneers in the field had worked hard to see design programs established in institutions of higher learning and for the acceptance of the principles of good design. Colleges and universities were turning out design graduates in numbers that made it easy to hire in-house expertise, and engineering programs were introducing practical design considerations to their students. Industrial design was becoming institutionalized, and, to some degree, the independents were victims of their own success. A trend toward the use of in-house designers had become noticeable in the mid-1950s. By the early 1970s, the change was profound and obvious. Marketing and advertising were increasingly driving the product development process, and internal pressure to cut costs and rush products out the door proved harder for in-house designers to resist. Quality sometimes suffered. The change may, in part, explain the reason that many consumers remember the 1970s as a decade marked by some of the worst products ever delivered to the American public.

For over twenty years, Huxtable had been the designer for most of Millers Falls’ new tools. The fragmentary records available indicate that his work for the company included planes, packaging, levels, drills, braces, saws, inclinometers, glass cutters, wrenches, hedge trimmers, and precision tools. While it may never be possible to identify all of his individual designs for the firm, there can be little doubt about the quality and quantity of his work and his place in mid-twentieth century hand tool development. In 1982, Garth Huxtable donated his papers to the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie. As most drawings and correspondence were retained by Millers Falls, the part of the collection relating to tool design is small, and much of this dates from the period when the designer worked almost exclusively with power tools. The collection currently resides at the Getty Research Institute.

Leonard Garth Huxtable died in 1989.

Illustration credits

- Plane-R-File: author’s photo.

- Linked image of permaloid-handled plane: author’s photo.

- Linked image of futuristic hack saw: Millers Falls Company. Hand Tools, Portable Electric tools, Hacksaws: Catalog No. 49. Greenfield, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1949.

- Linked image of No. 5 drill: Millers Falls Company. Catalogue no. 35. Millers Falls, Mass. : Millers Falls Co., 1915.

- Linked image of No. 104 drill: Millers Falls Company. Hand Tools, Portable Electric tools, Hacksaws: Catalog No. 49. Greenfield, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1949.

- Linked image of plane with red plastic handle and knob (Buck Rogers plane): author’s photo.

References

- L. Garth Huxtable papers. Collection no. 8158, Box no. 5, unnumbered folder. American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie. (Collection currently resides at the Getty Research Institute.)

- The wondrous decline in the cost of the Model T is often reported and frequently used to illustrate the benefits of mass production. Arthur Pulos uses the example in his landmark design history. The American Design Ethic: a History of Industrial Design to 1940. MIT Press, 1988. p. 252-256.

- Arthur J. Pulos. The American Design Ethic: a History of Industrial Design to 1940. MIT Press, 1988. p. 344.

- United States Design Patent No. 140,810, April 10, 1945.

- U. S. Industrial Design, 1949-1950. New York: Studio Publications, 1949. p. 130.

- L. Garth Huxtable papers. Collection no. 8158, Box no. 5, unnumbered envelope marked “Patents.” American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie. (Collection currently resides at the Getty Research Institute.)

- Arthur J. Pulos. The American Design Adventure, 1940-1975. MIT Press, 1988. p. 344.