Leander W. Langdon

Early years

Leander W. Langdon, the inventor of the Langdon miter box, is reported to have been born in Jay, Vermont, in 1833. Little is known about his youth or family circumstances, although he would later relate that he became fascinated with sewing machines at age thirteen while employed in the shop of Daniel Rall in Rochester, New York. After reading a newspaper article about a feeder device that simplified the sewing of curved seams, he constructed a model feeder from a wooden shingle—one that remedied the defects of the original. Langdon also reported that he had built a working sewing machine of his own design at age seventeen in the Rochester shop of a Mr. Wright.(1)

Although the details of Langdon’s youthful accomplishments are questionable—they were given as testimony in a patent case in which he may have benefited financially—there is little doubt that he was a talented young man. By 1851, he was working on the construction of A. B. Wilson sewing machines in the shop of a Mr. Burroughs, and by 1852, he was working on a second machine of his own design. On October 30, 1855, Langdon was issued United States Letters Patent No. 13,727, and he began to manufacture sewing machines under his own name.

Langdon exhibited his sewing machine at the New York City Crystal Palace, a glass and iron exhibition hall originally built for the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, the world’s fair of 1853. Samuel Lapham Hill, a wealthy industrialist from Florence, Massachusetts, was impressed with Langdon’s invention and arranged to have the manufacture of the machine moved to his home town. Hill was the president of the Nonotuck Silk Company, and it is likely that his interest in the sewing machine owed much to the fact that a growing market for the devices was powering sales of the machine-twist silk thread manufactured by his business.(2)

Hiram Wells & Company

Production of the Langdon machines moved to Hiram Wells & Company (later Wells, Littlefield & Co.), a Florence-based firm that manufactured circular sawmills, pumps and grip wrenches. The choice of the Wells shop was an obvious one—S. L. Hill and his associate Daniel Greene Littlefield were major investors in the operation. Leander Langdon was set to work on the development of an improved sewing machine, and on March 20, 1860, he was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 27,594 for a new version of his hand-cranked sewing machine.(3) Nine months later, he patented for an improved shuttle. Langdon shared the rights to the patents with his co-assignees, D. G. Littlefield and the late Hiram Wells. The resulting machine featured a four-motion feed and maintained even tension on the thread while a piece of fabric moved through it. Four years in development, the device was anything but easy to manufacture. The first ten machines took 18 months to build and cost the operation $10,000—a princely sum at the time. As the production problems were worked out, Wells, Littlefield & Co. arranged to have the machine licensed by the powerful Sewing-Machine Combination.(4)

The Sewing-Machine Combination—also known as the Sewing Machine Trust—had been formed in 1856 to bring some peace to a particularly brutal spate of patent wars. While not violent, the legal battles were expensive, and they were complicated enough to threaten the development of the industry as a whole. The trouble had started with a patent battle between pioneer inventors Isaac Singer and Elias Howe. Taking years to litigate and generating a transcript of over a million pages, the conflict created a situation where anyone making a sewing machine was likely to be sued by one party or the other. When Howe finally won the case, he was awarded a royalty on every sewing machine manufactured in the United States, but the air had become so poisonous that nearly every improvement, whether by Howe or others, generated additional lawsuits.(5)

The president of the Grover and Baker Sewing-Machine company, Orlando B. Potter, convinced the companies that working together would be more profitable than fighting continual legal battles. The major producers pooled their patents and developed a system of licensing and royalties that ensured newcomers entering the field would make payments to what became known as The Combination. Although members of the Combination cooperated in the granting of licenses, they remained free to develop, manufacture and market machines in competition with one another. The group was diligent in protecting its patents—a portion of the licensing revenues was set aside for the prosecution of infringers.(6)

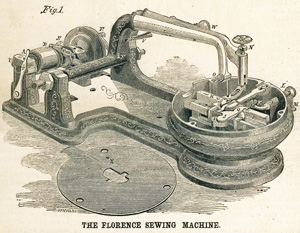

Florence Sewing Machine Company

In 1861, D. G. Littlefield and S. l. Hill assembled a group of investors and established the Florence Sewing Machine Company. The operation was capitalized at $125,000 and Littlefield became the firm’s first president. Only fifty of Langdon’s machines were sold that first year. Sales increased to 1,100 in 1862 and the total capitalization to $200,000. On July 14, 1863, Leander Langdon patented an innovative and much admired reverse feed for the machine. Sales increased to 6,000 machines annually, and construction began on the new brick factory that would house the operation. By 1866, the payroll had grown to 350, production had increased to 1,500 units per month, and a total $500,000 had been invested in the business.(7)

The Florence sewing machine’s success was due, in large part, to its versatility. An 1868 guidebook to the Connecticut Valley noted:

It makes four different stitches, the lock, knot, double lock, and double knot, on one and the same machine. Each stitch being alike on both sides of the fabric. Every machine has the reversible feed motion, which enables the operator, by simply turning a thumb screw, to have the work run either to the right or left, to stay any part of the seam, or fasten the ends of seams, without turning the fabric. The only machine having a self-adjusting shuttle tension, the amount of tension always being in exact proportion to the size of the bobbin. Changing the length of stitch, and from one kind of stitch to another, can readily be done while the machine is in motion. The needle is easily adjusted. It is almost noiseless and can be used where quiet is necessary. Its motions are all positive; there are no springs to get out of order, and its simplicity enables the most inexperienced to operate it.

It does not require finer thread on the under than for the upper side, and will sew across the heaviest seams, or from one to more thicknesses of cloth, without change of needle, tension, or breaking thread. The Hemmer is easily adjusted, and will turn any width of hem desired. No other machine will do so great a range of work as the Florence. It will hem, fell, bind, gather, braid, quilt, and gather and sew on a ruffle at the same time.(8)

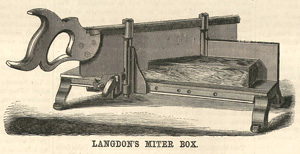

The Langdon miter box

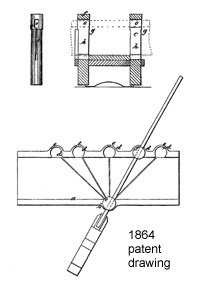

L. W. Langdon made no significant contributions to sewing machine development after the patent of his reverse feed in 1863. It may be that his affiliation with the Florence Sewing Machine Company ended shortly thereafter. On November 24, 1864, he was awarded two new patents, neither of which related sewing machines and neither of which can be linked to the principals of Florence Sewing. United States Letters Patent No. 45,054 was issued for a screw-cutting machine; No. 45,055 was issued for a miter box.

Langdon’s original miter box was designed to accurately hold a saw at any of a series of pre-set angles. Although he is widely credited with the development of the cast iron miter box, his contribution to miter box design actually consisted of the use of rotating, cylindrical saw guides. Oddly, the tool pictured in the original patent drawings was equipped with an adjustment for the angle of the cut that was located at the back of the box rather than the front. The angle was set by sliding a cylindrical saw guide into one of several tubes incorporated into the rear of the frame. It is not known if a miter box with this back-of-box adjustment was ever manufactured.

The earliest illustration of a commercially available version of Langdon’s box appears to be that published in the May 11, 1867, issue of Scientific American. This miter box is adjustable at the front by means of a sliding guide that could be locked into place with a dowel pin and a thumb screw. The box was manufactured by the Langdon Mitre Box Company of Northampton, Massachusetts. Little is known about the company’s earliest years, although it is likely that it did not own a production facility. Langdon miter boxes were manufactured at the Northampton Pegging Machine Company until 1875 when production moved to the factory owned by the Millers Falls Company.

Langdon’s second miter box patent was issued May 19, 1874, and with this design, the tool took its modern form. The new box featured a cylindrical saw guide fixed to a pivoting arm that passed under the table of the box and could be locked into position at the front. For the next century, most miter boxes would follow this pattern.

Billiards and beverages

God-fearing mothers would not have considered Leander Langdon an appropriate role model for their sons. A frequenter of billiard parlors and liquor locales, Langdon experienced the occasional dust-up with the law. On January 2, 1865, he was fined twenty-five dollars and costs for an assault on William A. Govern of North Hadley. Later that year, he was arrested for selling non-medicinal alcoholic beverages, a practice banned by a state-wide prohibitory law. He was subsequently involved in an assault on the law enforcement officer who testified against him. S.E. Eastman, the prohibitionist editor of the Greenfield Gazette & Courier reported:

Deputy Constable Chapin of Springfield, was violently assaulted, but not much injured, on Monday at Northampton, by L. W. Langdon and John Hannah. Mr. Chapin had furnished evidence of liquor sales by Langdon, for which he was arrested, and was in Northampton for the purpose of testifying in the case. It was while passing up the stairs to Justice Peck’s office that the assault was made, but Langdon and Hannah got the worst of it. Northampton has some of the worst liquor sellers in the state.(9)

His fiery temper aside, Langdon was an excellent billiards player. In February 1865, “Lee” W. Langdon signaled his intention of competing for the Gold Cue in the Tournament for the Championship of Massachusetts. The five-day tournament began on March 13 at Bumstead Hall, on Winter Street in Boston. The game, four-ball carom, was played on six-by-twelve-foot, four-pocket tables made by Phelan and Collender. L. W. Langdon came in fourth in a field of eight and won a silver cup for his efforts. The following year, Langdon attempted to wrest the title from the reigning Massachusetts state champion, Edward Daniels. On February 21, 1866, he played a four-hour and forty-four minute match against Daniels at Bumstead Hall. Lee Langdon’s fifty-ball runs were no match for Daniels’ hundred-ball onslaughts; the inventor lost 1500 to 1252.(10)

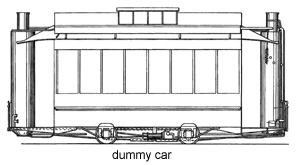

A dummy car

Certainly the most unusual of Leander Langdon’s inventions was the dummy car he patented on November 30, 1869. While a contemporary reader might picture the device as an automobile for the slow-witted, a Victorian reader would have immediately understood that the term referred a railway car equipped with its own engine. Langdon’s dummy was a steam-powered street car equipped with a boiler at each end, water tanks under the seats, an engine located under the carriage and between the wheels, and condensers on the roof. The odd locations of this equipment served to maximize the car space that was available to house passengers.

Designed to replace the horse-drawn cars in use at the time, there is no evidence that the dummy was commercially successful. Attempts to test the prototype met with much resistance from Northampton residents who were concerned about the impact of the car’s noise and commotion on their peace and quiet. After some wrangling, local authorities approved the operation of Langdon’s dummy. The Lowell Daily Citizen and News noted:

In Northampton, Wednesday, immediately after the vote was passed allowing the dummy engine to run upon the Williamsburg street railway, Mr. Langdon, the inventor, steamed up into Main street with an overwhelming load of passengers, whose waving of handkerchiefs and shouts of triumph were not a very welcome demonstration to the owners of frisky horses, who had tried so hard to discontinue the use of the new and valuable invention of Mr. Langdon in the streets.(11)

Final years

Leander Wesley Langdon was not destined for old age. He died of tuberculosis in Jacksonville, Florida, on January 26, 1875, at the age of forty-two. Although he had continued to register new patents in the months prior to his demise, he had been in failing health for several years. Langdon was visiting Jacksonville in the hope that the climate would improve his health—something that an earlier trip to the Pacific Coast had failed to accomplish. Although he was a successful inventor, his illness had taken its financial toll by the time of his death. Leander Langdon left an estate that was declared insolvent and was inadequate to provide for his family.

Leander Langdon Patents

| Patent Number | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 13,727 | October 30, 1855 | sewing machine |

| 27,594 | March 20, 1860 | sewing machine—assigned to self, Hiram Wells and D. G. Littlefield |

| 30,826 | December 4, 1860 | valves of oscillating machines |

| 31,211 | January 22, 1861 | sewing machine—assigned to self, Hiram Wells and D. G. Littlefield |

| 39,256 | July 14, 1864 | sewing machine—assigned to self and D. G. Littlefield |

| 45,054 | November 11, 1864 | screw cutting machine |

| 45,055 | November 11, 1864 | miter box |

| 91,139 | June 8, 1869 | permutation lock—assigned to self and J. G. Clark |

| 97,300 | November 30, 1869 | applying steam power to street cars |

| 97,414 | November 30, 1869 | stove damper—assigned to self and Edwin R. Locke |

| 141,236 | July 29, 1873 | sewing machine caster—assignee with J. Robertson; invented by Robertson |

| 151,139 | May 19, 1874 | miter box |

| 155,318 | September 22, 1874 | magazine firearms |

Illustration credits

- 1867 Langdon miter box: Scientific American. May 11, 1867, p. 296.

- Florence sewing machine: Scientific American. January 1, 1866, p. 1.

- Linked image of Florence Sewing factory: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. April 28, 1866, p. 84.

- Miter box drawings: United States Letters Patent No. 45,055 (edited by author)

- Langdon dummy car: United States Letters Patent No. 97,414 (edited by author)

References

- Samuel S. Fisher. Reports of Cased Arising Upon Letters Patents for Inventions: Determined in Circuit Courts of the United States. 2nd ed. Cincinnati: Robert Clarke and Co., 1871. Vol. 2. p. 105-115.

- Henry M. Burt. Burt’s Illustrated Guide to the Connecticut Valley. Northampton: New England Publishing Co., 1867. p. 90.

- Agnes Hannay. “A Chronicle of Industry on the Mill River.” Smith College Studies in History, v. 21, nos. 1-4. p. 75-80.

- Burt. p. 90.

- Grace Rogers Cooper. The Sewing Machine: its Invention and Development. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1976. p. 40-42.

- William Ewers and H. W. Baylor. Sincere’s History of the Sewing Machine. Phoenix: Sincere Press, 1970. p. 39-40.

- Charles Arthur Sheffeld. The History of Florence, Massachusetts: Including a Complete Account of the Northampton Association of Education and Industry. Florence, Mass.: C. Sheffeld, 1895. p. 242.

“The Great Workshops of America: the Florence Sewing Machine Company’s Works.” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, no. 552, (April 28, 1866). p. 84. - Burt. p. 90.

- “Hampshire County Items.” Gazette and Courier. (Greenfield, MA) Dec. 25, 1865.

- Michael Phelan. The American Billiard Record: a Compilation of Important Matches Since 1854. Boston: Phelan and Collender, 1870. p. 33, 46.

- “In Northampton...” Lowell Daily Citizen and News (Lowell, MA) August 21, 1869.