Quimby S. Backus

A slightly expanded digital version of the two-part article appearing in the June and September 2007 issues of The Gristmill: the Journal of the Mid-West Tools Collectors Association.

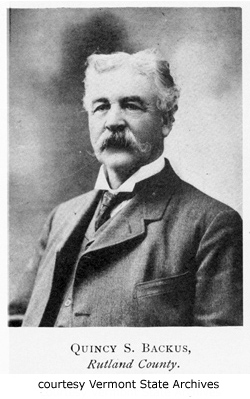

Quimby S. Backus, the newly elected senator from Rutland County, must have been disappointed. On the heels of a successful campaign for elective office, the publisher of the state’s 1902 biographical register mangled his first name on the identification beneath his handsome and stylish portrait.(1) Backus was sixty-four years old, semi-retired, and had brought his manufacturing business back to his home state a year or two earlier. His entry into politics was not unusual for a man of his experience, as at the time, it was commonplace for a successful businessman who had achieved a certain level of financial security to turn to politics in his later years.

Backus was born in 1838 to a middle-class home at Bridgewater in Windham County, Vermont. His father, Gurdon Backus, was a Methodist minister; his mother, the former Wealthy Ann Hoisington, had come from one of the long-established Bridgewater families. When Quimby was a boy, Gurdon Backus moved the family to Brandon, Vermont, and there the younger Backus received an education typical for a middle-class youth—an elementary education in the public schools followed by graduation at age sixteen from the local academy. Having received his diploma, Quimby Silas Backus moved on to Woodstock, Vermont, where he began work as a machinist.

In 1857, John Howe formed the Howe Scale Company to manufacture weighing devices in Brandon, and Backus returned to his hometown to become one of the first men to take a position with the new firm. Howe had purchased the rights to a scale equipped with a ball-bearing pivot support that had been designed and patented by Frank M. Strong and Thomas Ross for the Sampson Scale Company of Vergennes, Vermont. The Strong and Ross scale was superior to its competitors in that its unique support system reduced stress on the scale’s pivot—decreasing wear and increasing its sensitivity. Howe Scale prospered and became a leader in its field, establishing an international reputation and continuing to manufacture high-quality weighing devices into the twentieth century. Although he was an early hire who worked on the first scale to pass through the doors of the Brandon plant, Quimby Backus remained with the Howe Scale Company for just four years.(2)

The Windsor Armory

The four years were long enough, however, for Backus to marry and start a family. In 1858, he married a local girl, Lavinia Lawrence, and their son Frederick Ellsworth was born in 1861—the year that Quimby left Howe Scale to become a toolmaker in the armory at Windsor, Vermont. Although the significance of his new workplace likely escaped him, Backus was going to work in the factory where gun makers Samuel Robbins and Richard Lawrence had developed a groundbreaking method of mass production in which products were assembled from interchangeable parts. The methodology, which required highly accurate precision machinery, eventually became known as the “American System” and was adopted by manufacturers worldwide. As visionary as their system was, it did not prevent an overextended Robbins & Lawrence from going bankrupt in 1857 when the British government abruptly canceled a large order of muskets following the end of the Crimean War.

Lamson, Goodnow & Yale purchased the failed armory, and it was with this firm that Quimby Backus found employment. His new bosses had contracted with Samuel Colt to produce the Special Model 1861, a .54 caliber rifled musket, and Backus was part of the production effort. The Windsor Armory would turn out 50,000 of the firearms between 1861 and 1865. Some of the finest mechanics in New England—men like Quimby Backus; Henry D. Stone, the popularizer of the vertical turret lathe; and William H. Barber, the inventor of the famous bit brace—were to pass through the doors of the Windsor Armory. Their influence on the Connecticut Valley and its hardware industry would be felt for decades.

First patents

As the war effort wound down, employment at the armory dwindled. Quimby Backus moved to Rutland, Vermont, where he secured employment in the car shop of the Rutland & Burlington Railroad. The railroad had just acquired the Brandon Car Company from William M Field and David Warren and had moved its equipment to a new facility designed for the production and maintenance of rolling stock. The work must not have suited Backus for he did not stay long. By 1868, he had relocated to Winchendon, Massachusetts, where he became involved in the design and patenting of tools and machinery. Between the summer of 1868 and the spring of 1870, the United States Patent Office issued six patents to Quimby Backus—three for vises, one for a stationary drill bit, one for a wooden spool labeler, and one for a valve-facing process for steam engines.

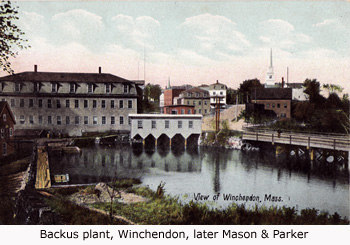

The stationary drill bit belonged to that class of tools in which the workpiece, rather than the bit itself, is rotated during the drilling process. The wooden spool labeler was a complex, multi-geared device that remains interesting not so much for its design as for its disposition. Backus assigned interests in the patent to himself and two men active in Winchendon’s wooden ware industry—Sidney Fairbanks and Orlando Mason. Mason owned a sawmill and factory that produced three-hooped pails and wooden boxes, and when Quimby Backus left the area to set up a manufacturing business, the men remained in contact. Several years later, Backus would return to Winchendon to establish a bit brace factory, and in the late 1880s, Orlando Mason and Homer N. Parker would set up a partnership there to produce his braces for him. The firm, Mason & Parker, eventually became a well-known manufacturer of children’s toys.

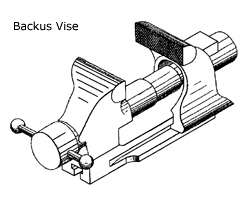

An advertisement on page 26 of the Worchester Directory for 1869 indicates that Q. S. Backus was manufacturing hardware and operating a sewing machine distributorship while working on his inventions in Winchendon. His three vise patents became the basis for a new enterprise, the Backus Vise Company. The most important, United States Letters Patent No. 78,565, was issued for a vise with its screw enclosed in a telescoping tube that protected it from dirt and shavings. Eager to secure as much protection for his idea as possible, Backus applied for and received United States Design Patent No. 3,130 which covered the vise as well. His third vise patent, No. 91,068, was issued for a telescoping tube vise equipped with a bench mount that allowed it to be rotated or repositioned by sliding it back and forth. The Backus Vise Company was organized on August 27, 1869. The operation was headquartered in Windsor, Vermont, where it leased shop space from the Windsor Manufacturing Company. By the following May, it was turning out 400 vises per month. Capitalized at $30,000, one-third of the shares were allotted to Quimby Backus as payment for his patents and the small business he had been operating. J. S. Farnsworth served as company president, R. H. Lamson as treasurer, and Quimby Backus as plant superintendent.(3)

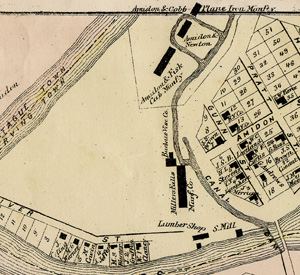

The Backus Vise Company left Windsor almost as soon as it opened. Lured by investment capital put up by Levi Gunn and Henry L. Pratt, two of the principals in the Millers Falls Mfg. Company, the operation moved to Grout’s Corner, Massachusetts in 1870 and set up shop on the larger firm’s canal. Quimby Backus and Moses Newton, the man who replaced R. H. Lamson as company treasurer, followed. Backus Vise set up in the Millers Falls boiler room, and shortly after the move, construction began on an adjacent wooden building to house its forging, polishing, and packing operations.(4)

The Backus operation was never large. Employment varied between sixteen and twenty-five, and under the supervision of Frederick Hubbard, the small but productive workforce manufactured a line of products that ranged from diminutive hand-held vises to jeweler’s vises to 168-pound blacksmith models. The extent of its product line was due, in part, to the acquisition of patents once held by the Union Vise Company. Union, a Boston-based firm, manufactured forty styles and sizes of vises prior to its destruction by fire in 1871. As Backus Vise had no foundry, rough castings for its products were purchased from the Clark & Chapman Machine Company in nearby Turners Falls and finished locally.

The Backus Vise Company was plagued by misfortune. In December 1871, production was halted when a fire burned out the part of the operation housed in the Millers Falls boiler room. A year later, the vise company’s new wooden building burned to the ground. As demand for the vises exceeded production capacity, Millers Falls Manufacturing overlooked the problems of its tenant and installed yet another Hunt, Waite & Flint turbine to power the Backus Company’s growing operation. Despite near-constant woe, Backus Vise managed to reward its investors with ten-percent dividends. In January 1873, the vise company was merged with the larger firm to form the new Millers Falls Company. Quimby S. Backus had already moved on. He’d left the area months earlier to begin manufacturing a series of tools that he’d designed and patented the previous year.(5)

Backus & Company

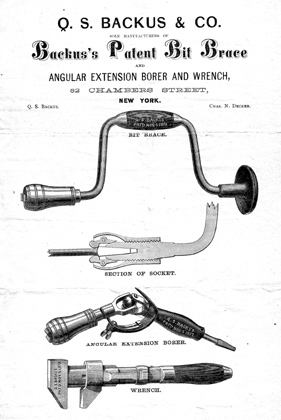

In fall of 1872, Backus and his partner, Charles N. Decker, established Q. S. Backus & Company and opened a sales office in the New York City hardware district at 82 Chambers Street. The company’s first price list, dated November 15th, included just three products—a bit brace, an adjustable angular bit stock, and a wrench—all designed by Quimby Backus and all covered by patents published just ten days earlier.(6) The price list made no mention of the location of the firm’s factory, but noted that "we are now entering orders for delivery in January and February." The firm’s first tools were likely manufactured at Winchendon as Backus listed the city as his residence on an 1874 application for a gage patent.

The 1872 price list proudly noted that the new adjustable Backus patent wrench did not incorporate a standard screw-type adjustment and emphasized the speed at which its sliding mechanism could be set. Since the wrench’s sliding jaw was not lockable, it relied on the friction created during the tool’s use to hold the jaw in place, and the strength of its grip increased as greater force was applied to it. Backus and Company initially offered the wrench in eight, ten, and twelve-inch sizes. Although its adjustment mechanism was identical to that in the original patent drawings, the wrench depicted in the price list was fitted with a wooden handle and differed in the squared-off profile of its jaws. An English version of the wrench, lacking a wooden handle and with jaws similar to that in the patent, has been reported. It is stamped "R. Timmins & Sons," the name of a prominent Birmingham tool supplier.(7)

At the time of its introduction, the Backus adjustable angular bit stock was far more sophisticated than similar devices on the market. Its single universal joint and bifurcated design, however, were not patentable features, and as a result, protection was limited to its locking adjustment mechanism. Similar tools were soon offered, most notably the angular bit stock developed by James Anthoine and marketed by the Millers Falls Company. Anthoine substituted a sheet metal adjustment for Backus’s cast design and rotated it ninety degrees. The change was enough to convince the Patent Office that the design was worthy of protection, for Anthoine was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 171,255 just three years later.

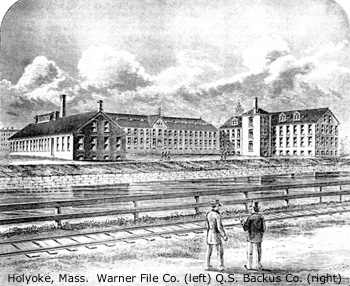

For reasons unknown, the Q. S. Backus operation relocated to Holyoke, Massachusetts. Although the timing of the move is uncertain, manufacturing was underway at the new site by 1876. Situated on the Connecticut River, Holyoke was a booming manufacturing center with a huge dam and an elaborate, three-level system of mill canals. The Q. S. Backus Company made its tools in a three-and-one-half-story building in Holyoke at the intersection of Appleton Street and the city’s Second Level Canal. Production moved back to Winchendon in the early 1880s; the New York sales office moved to 102 Chambers Street at about the same time.

For reasons unknown, the Q. S. Backus operation relocated to Holyoke, Massachusetts. Although the timing of the move is uncertain, manufacturing was underway at the new site by 1876. Situated on the Connecticut River, Holyoke was a booming manufacturing center with a huge dam and an elaborate, three-level system of mill canals. The Q. S. Backus Company made its tools in a three-and-one-half-story building in Holyoke at the intersection of Appleton Street and the city’s Second Level Canal. Production moved back to Winchendon in the early 1880s; the New York sales office moved to 102 Chambers Street at about the same time.

Early Backus bit braces

The Q. S. Backus Company’s first bit brace featured a cast iron head painted red on the inside and a rotating sweep handle similar in appearance to that patented by Clemens Rose in 1868. The frame, manufactured of wrought iron, was available with a 6, 8, 10, 12, or 14-inch sweep. The patented chuck was equipped with two short jaws that pivoted on pins that pierced the chuck shell. As the chuck was tightened, a conical taper at the end of the brace’s socket caused the jaws to rotate forward onto the shaft of a bit, firmly seating it in the square, tapered hole of the socket. The arrangement was simple but effective.

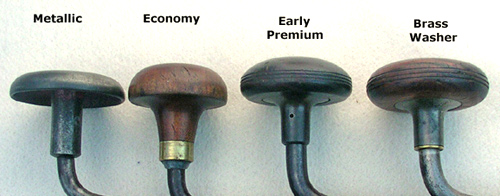

Backus & Company soon moved away from the use of metallic heads on its premium braces, replacing them with lignum vitae. A second category of economy-grade models with wooden parts of domestic hardwood was introduced as well. The lignum heads were simply threaded onto a brace’s quill; the economy-grade heads were held in place via a friction fit. Neither attachment mechanism was innovative. Domestic hardwood heads were forced down over a hollow wooden cylinder in the manner of a number of other vendors. The cylinder, sometimes wrapped with string, was held captive between a bolster and, at top, a washer peened into place. The company later added a bolster made of a brass washer to its lignum vitae models, a change that reduced drag on the rotation of the head.

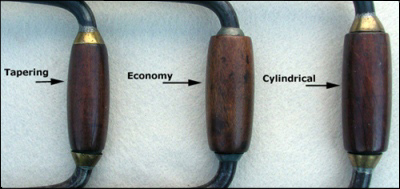

The 1872 brace patent also covered the sweep handle. The original Backus handle had more in common with the 1868 Clemens Rose design than just its shape. Both incorporated cup-like metallic retainers that were soldered to the frame to hold a wooden handle whose tapering curves fit inside them. The Rose patent assumed the wooden handle would be manufactured in two pieces, then added to the brace and joined together; the one-piece Backus handle was designed to slip over the frame before the rod was bent. The text of Rose's patent anticipates most of the changes Backus made to the design. Although the sweep handles of the very first Backus braces were fabricated from domestic hardwood, rosewood became the norm for premium braces when the company introduced lignum vitae heads. The rounded, tapering profile of the sweep handles gave way to a standard cylindrical shape sometime between 1880 and 1884.

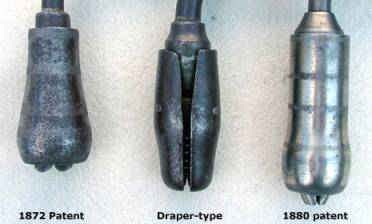

At some point prior to 1880, Quimby Backus acquired the rights to a brace patented by William W. Draper on July 11, 1865.(8) Draper, a resident of Greenfield, Massachusetts, had originally assigned one-half of the patent to himself and the other half to Alonzo Parker, one of the principals of the Greenfield Tool Company. Backus reworked the Draper design and came up with a brace that bore little resemblance to that depicted in the original patent drawings. The brace featured a bizarre-looking chuck that consisted of two massively oversized jaws pinned to a nut that traveled up and down the threads of its socket. As the nut traveled up the socket, the rear edges of the jaws encountered a cone that spread them apart. Since the jaws pivoted at mid-point, their front parts moved inward, closing over the shoulders of a square-tang bit. Backus Draper-type braces were offered with and without ratchets in both the economy and premium grades. The Backus bit brace gallery illustrates these and some of the other boring tools designed by Q. S. Backus.

Sued by the Millers Falls Company

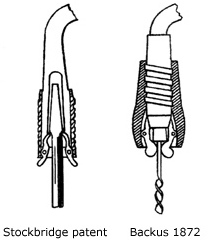

Unfortunately for Quimby Backus, his former associates at the Millers Falls Company took a dim view of the chuck described in his 1872 patent. The company was moving aggressively to protect its leadership role in the manufacture of bit braces by working to have its patents re-issued and buying related designs in an attempt to control the manufacture of what it defined as “grip-type” braces. One of its acquisitions was a patent for a bit brace developed in 1867 by Charles H. Stockbridge of Whately, Massachusetts. Millers Falls succeeded in getting the patent re-issued in 1875, and it became the basis for a lawsuit against Backus.

When the issue came to a final hearing on December 12, 1879, the Backus attorneys did not defend the 1872 patent on its own merits, but rather on its similarity to the Draper patent, believing, perhaps, that a design pre-dating Stockbridge would have the advantage. At issue was the extent to which the Backus shell-type design allowed the jaws to grip the rounded shank of a bit. In his defense, Backus maintained that the jaws served merely as wedges, engaging the shoulders of a square-tang bit to keep it from being pulled out. Judge John Lowell of the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Massachusetts found otherwise. The case was decided for the Millers Falls Company, and the chuck described in the 1872 Backus patent was invalidated.(9)

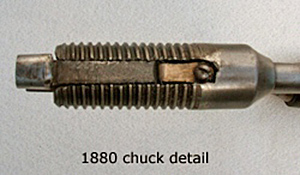

Although the Draper patent itself remained valid, the loss of the Q. S. Backus Company’s flagship chuck was a major setback for the firm. The non-infringing Backus adaptation of Draper’s design, with its huge oversized jaws, did not function particularly well with small-sized auger bits but served for a time as the stopgap standard for the company’s bit braces. An ad in the August, 1880, issue of Carpentry and Building depicts the Draper-type design and notes, "This socket is used on all of my patent braces, comprising every grade of quality and finish..." Backus responded to his courtroom misfortune by developing and patenting two chucks during the next ten months. On the basis of the new patents, the Q. S. Backus Company began manufacturing braces that featured a shell-type chuck with two opposing grooves cut into the exterior of its threaded socket. Within each groove, a strap-type spring engaged a notch in the rear of the jaw. As the shell was loosened on the threaded socket, pressure from the springs forced the jaws apart. The 1880 self-opening chuck, stamped with October 19th and November 16th patent dates, became the operation’s new standard.(10)

Another lawsuit

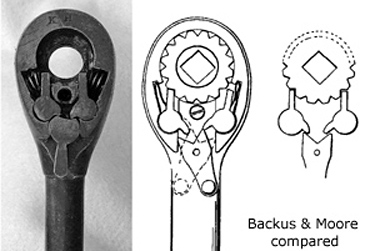

Just six weeks after the loss of the Millers Falls case, the attorneys for Quimby Backus were again back in Judge John Lowell’s courtroom. John E. Sinclair and his associates were suing Backus for infringement of D. M. Moore’s patent for a ratcheting wrench. At the time, Backus was marketing what may have been the first commercially viable American brace to incorporate an enclosed ratchet in its design, and that ratchet was virtually identical to the one used on Moore’s wrench. The case is especially interesting in that Moore and Backus had once worked in the same shop, and it is quite likely Backus appropriated the idea.

D. M. Moore had developed his ratchet wrench in 1859. Manufactured for his personal use, he took it with him as he traveled from job to job. In 1861, when Moore moved to Windsor, Vermont, to join the influx of workers who signed on at Lamson, Goodnow & Yale for the Samuel Colt musket project, his wrench accompanied him. Moore used the wrench regularly, lent it to others when asked, and made a duplicate for the armory tool room when it became popular with his fellow workers. Proud of his wrench, Moore was known to have disassembled it to show others the details of its ratchet. Although he did not apply for a patent until October 1, 1864, he attempted to interest investors in his design during his time at Windsor. The patent, No. 45,334, was issued that December.(11)

There can be little doubt that Quimby Backus found occasion to use Moore’s wrench during the years that the men were co-workers at the Windsor Armory and that he knew the details of its construction a decade or more before he began using a look-alike on his bit braces. The Backus attorneys challenged the validity of Moore’s patent on the grounds that the wrench was "in public use or on sale for more than two years before the application of the patent." Judge Lowell disagreed, ruling that Moore’s attempts to interest investors in the wrench did not translate into its being "on sale" and that its limited use was not public and amounted to little more than evaluation and testing. The Backus Company’s use of the ratchet was found to be infringing.(12)

Other ratchets

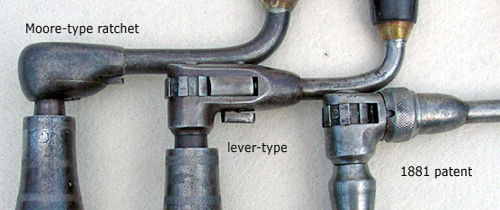

At the time of the Moore lawsuit, Backus was also manufacturing tools with an exposed ratchet wheel, double-pawl arrangement. The direction of rotation and the ratchet lock were set by means of a small lever attached just beneath its spring-loaded pawls. In use as early as 1879, its design had enough commonalities with the Moore patent to preclude its continued manufacture. Inattentive observers sometimes confuse this lever-adjusted, exposed-pawl ratchet with that patented by Edgar H. Whitney in 1885. The Whitney ratchet, covered by United States Letters Patent No. 319,159, featured concealed, roller-type pawls rather than the exposed ratchet dogs seen on the 1879 Backus ratchet. Although Whitney lived in Winchendon, and may well have been an employee of Q. S. Backus, the writer has yet to see a Backus brace with the Whitney patent.

The Backus lever-adjusted ratchet became the basis for one of the more unusual tools that the company marketed—an adapter that converted a standard bit brace into a ratcheting model. Given that the most expensive and time-consuming part of manufacturing a ratchet brace is the machining and fitting of the ratchet and chuck, the economics of the adapter’s manufacture are hard to understand. With the efficiency and convenience of a brace with an integral ratchet available to a worker for a comparatively reasonable price, the market for the device must have been limited. Although the ratchet adapter could have been used to convert a standard breast drill into a ratcheting model, it appears that sales were anything but robust. Adapters with a post-1880 chuck have yet to be observed.

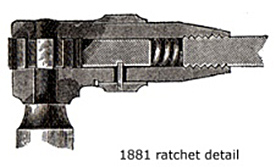

On November 29, 1881, Quimby Backus was issued United States Letters Patent No. 250,047 for a bit stock ratchet with a ring shifter adjustment. The ratchet, in use since at least August of 1880, was elegant in its simplicity and featured a single concealed pawl with a tooth on its leading edge that engaged the notches of the ratchet wheel. Three sides of the tooth were parallel, and one side was cut with a beveled face. As the ring shifter was rotated, the pawl turned with it. Depending on its position, the beveled notch allowed ratcheting to the right or left. When parallel sides were engaged in the wheel, the ratchet was locked. A single heavy-duty spring provided tension for both pawl and ring shifter. The 1881 ratchet functioned well and stood up to hard use. It was, perhaps, the finest of the Backus tool patents.

Adjustable socket wrench

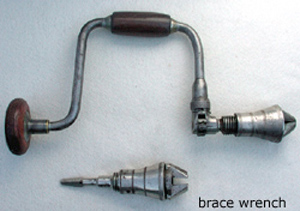

In 1879, Quimby Backus patented an attachment for converting a bit brace to a socket wrench. The drawings accompanying the published document illustrate both non-ratcheting and ratcheting versions of the tool.(13) The ratchet depicted is the lever-adjustment design used  on his adapter for converting a standard bit brace into a ratcheting model. The wrench patent covered the design of the chuck, and its text indicates that Backus planned to use the device on bit braces, angle borers, and tool holders. Capable of handling nuts from 1/4 to 1 1/4 inches, the company’s promotional material made it clear that the chuck was "peculiarly adapted to the use of mechanics, blacksmiths, carriage builders, agricultural implement manufacturers, millwrights, and in fact all branches of trade where nuts and bolts are used..."(14)

on his adapter for converting a standard bit brace into a ratcheting model. The wrench patent covered the design of the chuck, and its text indicates that Backus planned to use the device on bit braces, angle borers, and tool holders. Capable of handling nuts from 1/4 to 1 1/4 inches, the company’s promotional material made it clear that the chuck was "peculiarly adapted to the use of mechanics, blacksmiths, carriage builders, agricultural implement manufacturers, millwrights, and in fact all branches of trade where nuts and bolts are used..."(14)

Although the ratcheting version of the socket wrench attachment was manufactured and sold, its longevity is suspect as no examples with the 1881 single-pawl ratchet have been observed. The non-ratcheting attachment, with a longer production history, is more frequently seen, and braces with integral socket wrenches were developed and sold as well. Billed as “bit brace wrenches,” these tools were offered in ratcheting and non-ratcheting versions in both economy (domestic hardwood) and premium (tropical wood) grades. When used to loosen a stubborn nut, a fair amount of downward pressure was required if the chuck was not adjusted properly or the nut was hexagonal in shape. Examples of lignum-topped brace wrenches with their heads broken out by users applying excessive downward force are not unusual.

An interesting variant of the socket wrench chuck was an adapter described as an "adjustable socket angular wrench." Designed to allow a brace user to turn nuts and bolts in corners, the device differed from the Backus angular bit stock in that it was manufactured to operate at a fixed angle. The torque generated in tightening 1 1/4 inch nuts would have played havoc with the delicate angle adjustment mechanism used for the original Backus adjustable angular bit stock. By 1884, if not earlier, the casting for the angular socket wrench had become the norm for the angular bit stock as well, and the less-useful, fixed angle tool was referred to as an "improved" rather than "adjustable" angular borer.

1884 catalog

In late 1884, Q. S. Backus published a small thirty-two-page catalog divided into two parts. The first nineteen pages were titled Q. S. Backus’ Patent Portable Combination Cabinets and consisted of promotional material for bathing, washing, and toileting fixtures enclosed in elaborate wooden cabinets. The next thirteen pages were titled Q. S. Backus 1880 Patent Improved Boring Implements. A perusal of its contents reveals that, true to its title, the tool section includes only braces, adapters, and brace wrenches. The Backus adaptation of the Draper chuck is nowhere to be seen—an obvious indication that it was no longer in production. The Backus boring tool manufactory was never large, and at the time of the publication, it employed just twelve workers.(15)

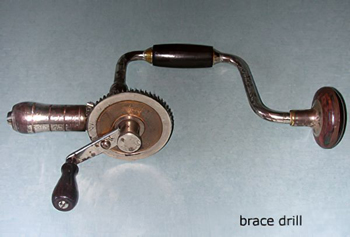

The boring tool section includes: ratcheting and non-ratcheting braces in economy and premium grades, a bit brace extension available in three lengths, the non-ratcheting socket wrench adapter, fixed-angle versions of the angular borer and socket wrench attachments, and a premium version of the brace wrench. Certainly one of the most interesting tools pictured is the Backus brace drill. Similar to the Millers Falls brace drill patented by Wallace Lyon in 1881, the tool’s toothed gear attachment was patented by Seymour A. Bostwick, an inventor from Chelsea, Massachusetts, whose 1879 application for patent protection pre-dated Lyon’s by nearly two years. Backus used his 1880 chuck design and the 1881 single-pawl ratchet for his version of the brace drill. Heavily nickel plated and fitted with a lignum vitae head and rosewood sweep handle, the tool was visually stunning. An example owned by the author exhibits the remnants of a paper disc that was glued to the inside surface of the drive gear. For the most part illegible, enough text remains to indicate that the disc identifies Backus as sole proprietor of his business and includes instructions for the operation of the ratchet.(16)

The first dozen pages of the catalog document the results of Backus's entry into the world of indoor plumbing. At the time, residents of the typical American home bathed in water heated on a kitchen stove and indoor toilet facilities were rare. Businessmen wanting to exploit the market for a convenient and comfortable bathing and toileting experience needed to be cognizant of the fact that most housing did not contain a separate room for these purposes. One solution to the problem was to develop wooden cabinets that  contained the necessary fixtures and could be easily installed in an existing room. By 1884, the Backus factory in Winchendon was heavily involved in the production of portable plumbing cabinets. Available in ash, cherry, and walnut, the plumbing cabinets presented "a neat and ornamental appearance as an article of furniture for a bedroom, sitting-room or parlor."(17) A seventy-five-gallon reservoir atop the larger cabinets supplied water to an eighteen-gallon boiler that was heated by a nickel-plated kerosene stove and provided more than enough water for a comfortable bath in a full-sized tub equipped with a sliding wash bowl. Models with swing-out commodes were available, as was a water closet disguised as a wardrobe. Of course, the cabinets containing these latter amenities needed to be connected to "soil-pipes."

contained the necessary fixtures and could be easily installed in an existing room. By 1884, the Backus factory in Winchendon was heavily involved in the production of portable plumbing cabinets. Available in ash, cherry, and walnut, the plumbing cabinets presented "a neat and ornamental appearance as an article of furniture for a bedroom, sitting-room or parlor."(17) A seventy-five-gallon reservoir atop the larger cabinets supplied water to an eighteen-gallon boiler that was heated by a nickel-plated kerosene stove and provided more than enough water for a comfortable bath in a full-sized tub equipped with a sliding wash bowl. Models with swing-out commodes were available, as was a water closet disguised as a wardrobe. Of course, the cabinets containing these latter amenities needed to be connected to "soil-pipes."

Shortly after the 1884 catalog was issued, Quimby Backus patented two unusual bedsteads. United States Design Patent No. 16203 was issued for a Murphy-type bed, that when folded up to the wall looked like a fireplace mantel with a mirror hung over it. Intended for small apartments, the faux fireplace was an attempt to beautify the underside of a folding bed. Not to be outdone, Backus patented an asbestos-lined bed that folded into the front of a fully functional fireplace just five months later. There is no evidence to indicate that either bed was manufactured. In December 1884, Backus found himself unable to meet the demands of his creditors, and with liabilities of $45,000, he would have been hard put to bring new products to market.(18)

Later operations

Quimby Backus became increasingly interested in the manufacture of heating devices and in 1888 established a business in Philadelphia to produce them. The new business was demanding, and he arranged for Orlando Mason and Homer Parker to manufacture his bit braces for him. Headquartered in Winchendon, Mason and Parker continued making the braces in the building that Backus had used. In 1891, Backus joined with A. D. Hermance, E. A. Rowley, and J. J. Crocker to form the Backus Manufacturing Company in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. The new company manufactured steam radiators, mantels, tiles, fireplaces, and gas logs. By 1892, sixty workers were employed at the site. The financing and sales end of the Backus bit brace operation was folded into the business although the manufacture of the boring tools remained with Mason & Parker in Winchendon. By the mid-1890s, Backus braces were out of production.(19)

In 1900, Backus moved his successful heater operation to his childhood home—Brandon, Vermont. There he established a plant and foundry that employed sixty-five workers on a five-acre site. The business, now known as the Q. S. Backus Company, had branch offices in Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and San Francisco. Dealerships were scattered across the country, and Fred Ellsworth Backus, Quimby’s only son, managed the plant. The elder Backus was responsible for the sales end of the operation and financial management. The Rutland and earlier Williamsport businesses manufactured a number of small S-shaped combination wrenches on which the word Backus is cast. Examples include wrenches marked Backus Mfg. Co., Williamsport, Penn.; Q. S. Backus Co., Brandon, Vt.; and Backus, Brandon, Vt. The wrenches vary little in size, and it is unlikely that they were ever offered to the general hardware trade but were manufactured instead to open valves and cocks on heating devices. Those simply marked Backus likely postdate the departure of the elder Backus from active participation in the business.

Q. S. Backus was a Republican at the time of his election to the Vermont Senate in 1902. His party had dominated the state’s political landscape for decades. Backus affiliated himself with Percival Clement, the publisher of the Rutland Herald and an opponent of the state’s prohibition on the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors. Clement favored local option—a system of allowing town governments to determine whether or not alcoholic beverages would be sold locally. Since prohibition in Vermont was unevenly enforced and corruption was evident, public sentiment was moving in the direction of the wets. Clement hoped to capitalize on it. A bit of a renegade, the well-to-do newspaper owner challenged established party leaders in a divisive bid to win the nomination for the governorship. Though his effort failed, the popularity of his position on local option led to the election of a number of his supporters. Quimby Backus, a member of the Local Option Committee, was among them.(20)

Six years later, Backus abandoned the Grand Old Party to run for Vermont state governor on the Independence League ticket. A brainchild of yellow journalist William Randolph Hearst, the Independence League was a reform party that attracted a good deal of attention during the early years of the twentieth century. Hearst hoped to parlay his leadership of the organization into the governorship of New York—and eventually the presidency—by capitalizing on the favorable publicity given him by his national newspaper syndicate. Unfortunately for Quimby Backus, the Independence League imploded in 1908, and his candidacy for the governorship attracted just 2.1 percent of the votes.

Quimby Silas Backus died at Brandon on December 29, 1912. He had been ill for some time. The heater business he had established had failed, and its factory was sold to satisfy creditors just a month earlier. His son, Frederick, and a group of investors re-established the business several weeks after the funeral. They named their business the Backus Heater Company.(21) Fred Backus left the operation shortly afterward.

Q. S. Backus Patents

| Patent Number | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 78,565 | June 2, 1868 | vise |

| D3,130 | July 28, 1868 | design patent for vise |

| 82,583 | September 29, 1868 | chuck drill |

| 86,627 | February 9, 1869 | spool labeler assigned to self, Sidney Fairbanks, Orlando Mason |

| 91,068 | June 8, 1869 | vise |

| 102,078 | April 19, 1870 | process for facing valves and valve-seats |

| 132,789 | November 5, 1872 | wrench |

| 132,790 | November 5, 1872 | angular bit stock |

| 132,791 | November 5, 1872 | bit brace |

| 204,416 | June 4, 1878 | bit stock |

| 216,776 | June 24, 1879 | bit stock wrench |

| 233,464 | October 19, 1880 | bit stock |

| 234,517 | November 16, 1880 | bit stock |

| 250,047 | November 29, 1881 | ratcheting bit stock |

| 275,011 | April 3, 1883 | combined bathing apparatus and commode |

| 279,905 | June 26, 1883 | boiler |

| 307,255 | October 28, 1884 | bathing cabinet |

| 307,256 | October 28, 1884 | drip pan for water closet bowls |

| 308,868 | December 9, 1884 | cabinet commode |

| D16,203 | August 18, 1885 | design patent for folding bedstead |

| 334,504 | January 19, 1886 | combined bedstead and fireplace |

| 344,511 | June 29, 1886 | combined heating and cooking stove |

| 344,512 | June 29, 1886 | steam heater |

| 344,513 | June 29, 1886 | oil stove |

| 374,333 | December 6, 1887 | radiator |

| 374,649 | December 13, 1887 | heat radiating mantel |

| 390,743 | October 9, 1888 | gas log and fireplace |

Frederick E. Backus patents

| Patents Number | Date | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 485,079 | October 25, 1892 | gas log fireplace |

| 560,017 | May 12, 1896 | fireplace lining |

| 563,005 | June 30, 1896 | fireplace heater |

Illustration credits

- Backus portrait: Jeffrey, William H. Vermont: a Souvenir of its Government, 1902-1903. S. l.: s. n., 1902.

- Vise drawing: United States Letters Patent No. 78,565 (edited by author)

- Map: F. W. Beers and G. P. Sanford. Atlas of Franklin Co., Massachusetts : from Actual Surveys. New York: F. W. Beers & Co., 1871.

- Cover of first price list: scan of original in author’s possession.

- Holyoke factory: The City of Holyoke: its Water Power and its Industries. S. l.: s. n., 1876.

- Chuck comparison drawings: United States Letters Patent Nos. 132,790 & 62,232 (edited by author)

- Backus/Moore ratchet comparison: author’s photo & drawing from United States Letters Patent No. 45,334 (edited by author)

- 1881 ratchet: Q. S. Backus 1880 Patent Improved Boring Implements. New York: Q. S. Backus, [ca. 1884].

- Backus factory at Winchendon: View of Winchendon Mass. Portland, Me.: Hugh C. Leighton Co., [postcard, ca. 1908].

- Bathing cabinet: Q. S. Backus’ Patent Portable Combination Cabinets. New York: Q. S. Backus, [ca. 1884].

- All photographs including linked photos: author.

- Linked drawings of Draper patent: United States Letters Patent Nos. 48,763 (edited by author)

- Linked angular socket wrench drawings: Q. S. Backus 1880 Patent Improved Boring Implements. New York: Q. S. Backus, [ca. 1884].

References

- William H. Jeffrey. Vermont: a Souvenir of its Government, 1902-1903. Montpelier, Vt: Watchman Co., 1902.

- “Quimby S. Backus.” Genealogical and Family History of the State of Vermont: a Record of the Achievements of Her People in the Making of a Commonwealth and the Founding of a Nation. New York & Chicago: Lewis, 1903. p. 536-537.

- “Home and Business Matters.” Vermont Chronicle. Bellows Falls, Vt., September 4, 1869. p. 4; Advertisement. Vermont Chronicle. Bellows Falls, Vt., February 5, 1870. p. 3.

- Thanks to Kendall H. Bassett for providing information on the officers of the Backus Vise Company via the firm’s letterhead. Letter, Fred C. Hubbard to Messrs. Norris H. Bragg & Sons, May 27, 1871. Mr. Bassett also provided information on the acquisition of the Union Vise Company patents.

- The bulk of the information about the Backus Vise Company, in its Millers Falls location, was located in the Gazette and Courier. Greenfield, Mass., 1870-Sept. 1873. The information was taken from small snippets scattered throughout widely divergent issues.

- The wrench: United States Letters Patent No. 132,789; the angular bitstock: United States Letters Patent No. 132,790; the bit brace: United States Letters Patent No. 132,791.

- Mr. Oldwrench. “An International Wrench?” Fine Tool Journal. v. 53, no. 4, spring 2004, p.16-18.

- United States Letters Patent No. 48,763.

- United States Patent Office. Official Gazette. April 13, 1880. p. 130-131.

- United States Letters Patent No. 233,464; United States Letters Patents No. 234,517.

- Benjamin F. Thurston. John E. Sinclair, et al. vs. Quimby S. Backus: Notes on the Closing Argument for the Defendant. Providence, R. I.: Angell, Hammett & Co., 1879.

- United States Patent Office. Official Gazette. June 29, 1880. p. 205-206.

- United States Letters Patent No. 216,776.

- Advertisement. Carpentry and Building. August 1880.

- The catalog consists of 32 consecutively numbered pages without a unifying title page or cover.

- United States Letters Patent No. 250,670; United States Letters Patents No. 225,682. Bostwick was also issued a patent for a pipe wrench in 1883: United States Letters Patent No. 271,595.

- United States Letters Patent No. 275,011.

- The asbestos lined bed: United States Letters Patent No. 334,504. Notice of financial problems: "Trade Embarrassments." Bradstreet's Weekly, December 20, 1884. p. 396.

- Information on the heating devices: “Miscellaneous Manufactures.” History of Lycoming County, Pennsylvania. Chicago: Brown, Runk, 1892. p. 366; Notice that braces had been “unavailable for some time”: Wood Workers’ Tools: Being a Catalogue of Tools, Supplies, Machinery and Similar Goods ... Detroit: Charles A. Strelinger & Company, 1897. p. 891.

- Mason A. Green. Nineteen-Two in Vermont: the Fight for Local Option, Ten Years After. Rutland, Vt.: Marble City Press, 1912. p. 49, 97, 179.

- “The Backus Heater Company.” Merchant Plumber and Fitter. Feb. 10, 1913. p. 134.