Goodell-Pratt Company History

The Pratt Family

A third-generation tool man, William M. Pratt, the founder of the Goodell-Pratt Company, built a business on the basis of his financial acumen and sales ability rather than an understanding of tool production and design.(1)

A third-generation tool man, William M. Pratt, the founder of the Goodell-Pratt Company, built a business on the basis of his financial acumen and sales ability rather than an understanding of tool production and design.(1)

His grandfather, Josiah Pratt, was the first of the family to be involved in tool manufacture. Born in Mansfield, Massachusetts, on January 17, 1802, Josiah became interested in ax production when his family moved to Buckland Center where he began working at a blacksmith shop, a business that made axes. Josiah liked forge work, and at age twenty-one, he traveled to Stansted, Quebec, where he assisted with the construction of the province's first trip hammer—a large, mechanized device used to shape red-hot iron and steel.

Josiah returned to the United States afterward and began manufacturing axes, edge tools, and scythe snaths in Charlemont, Massachusetts. In April 1832, he patented an axe-making machine and began turning out axes and edge tools using a trip hammer.(2) It was a good year, one in which his business turned out products valued at $7,087, a considerable sum and a sign of a successful operation. Josiah stayed on in Charlemont for eleven years before moving his operation to a site with better water power in Shelburne Falls. The most prominent of the Connecticut Valley's early ax makers, he was especially noted for the quality of the cast steel used in his products. Josiah and his wife, the former Catherine Hall, parented eight children. When Franklin J. Pratt, the first of their two sons, joined the family business, his father changed its name to Josiah Pratt & Son. When the second, Francis R. Pratt, joined the business, it became Josiah Pratt & Sons. Josiah Pratt retired from the tool business 1865 and died in 1887.(3)

Francis R. Pratt, Josiah's eldest son and William Pratt's father, was born in Charlemont, Massachusetts, in 1835. When Josiah moved the family to Shelburne Falls in 1843, Francis attended Shelburne Falls Academy and, up on completing his education, went to work in his father’s axe-making enterprise. He left the family business at age twenty-seven to take a position with W. H. Maynard & Company, a Shelburne Falls tool manufacturer. In 1867, Francis Pratt moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, to work in the office of Maynard’s wholesale grain dealership. Shortly after Pratt's departure, Maynard’s tool manufacturing operation became H. S. Shepardson & Company, a producer of such hardware items as braces, bits, awls, chisels, and farm tools employing thirty-seven men.

Francis R. Pratt, Josiah's eldest son and William Pratt's father, was born in Charlemont, Massachusetts, in 1835. When Josiah moved the family to Shelburne Falls in 1843, Francis attended Shelburne Falls Academy and, up on completing his education, went to work in his father’s axe-making enterprise. He left the family business at age twenty-seven to take a position with W. H. Maynard & Company, a Shelburne Falls tool manufacturer. In 1867, Francis Pratt moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, to work in the office of Maynard’s wholesale grain dealership. Shortly after Pratt's departure, Maynard’s tool manufacturing operation became H. S. Shepardson & Company, a producer of such hardware items as braces, bits, awls, chisels, and farm tools employing thirty-seven men.

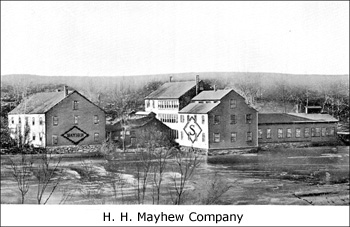

Francis Pratt returned to Shelburne Falls in 1872 to take up a position as superintendent of H. S. Shepardson & Company. When Shepardson died in 1876 and H. H. Mayhew purchased the business, Francis Pratt stayed with the operation, adding the title of manager to that of superintendent. He became the firm’s assistant treasurer in 1886, and on Mayhew’s death in 1894, company treasurer. When his son, William M. Pratt, purchased a controlling interest in Albert Goodell’s Goodell Tool company in 1907, Francis Pratt became its vice-president. The elder Pratt also served as a director of the Pratt Drop-Forge and Tool Company, an entity created by his son when he assumed control of Ducharmes & Company in Shelburne Falls.

William M. Pratt and Goodell-Pratt

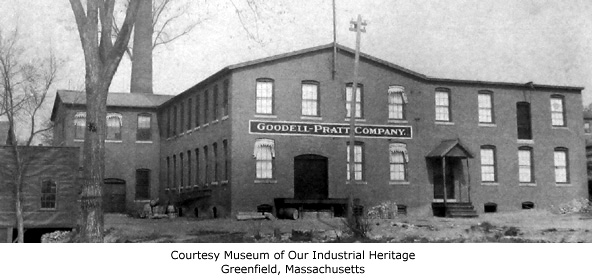

Born in Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, on August 13, 1867, William M. Pratt graduated at age sixteen from the Arms Academy, the local secondary school. He moved to Pukwana, a small town in central South Dakota in 1884 and worked there as editor and publisher of the Pukwana Press and as cashier for the Bank of Pukwana. The following year, he accepted a cashier position at the Case & Whitbeck Bank in the nearby town of Kimball. Life on the prairie must not have been to the young man’s liking for he returned to Shelburne Falls in 1890 to become secretary of the H. H. Mayhew Company, the hardware manufacturer where his father served as manager and plant superintendent. William Pratt did not stay with Mayhew long. He moved to Greenfield in 1892 to become a sales representative for the Wells Bros. Company, a tool producer that would eventually become Greenfield Tap & Die. In 1895, William Pratt purchased a fifty percent stake in the Goodell Brothers Company, a Greenfield manufacturer of carpenters' and mechanics' tools run by Dexter W. and Henry E. Goodell. With the purchase, Pratt became treasurer and manager of the operation. In 1898, he purchased a controlling interest in the business, and in February 1899, the company's board of directors voted to rename it the Goodell-Pratt Company.

A modest operation, the Goodell-Pratt Company was nicely positioned for growth. It occupied a factory less than ten years old and featured a product line diverse for an operation its size. When Pratt acquired controlling interest in the business, the lineup included push, hand, bench and breast drills, spiral screwdrivers, a bit brace, polishing heads, hack saws and blades, glass cutters, and hollow-handled tool sets. Its hack saw operation flourished due to its recent acquisition of Goodell, Son & Company. The Goodell-Pratt Company also owned the rights to a promising bench hack saw and had just developed a belt-powered hacksaw machine. Especially proud of the quality of its hacksaw blades, the company marketed them aggressively both at home and abroad. The foreign market initiative received a boost in 1900 when Goodell-Pratt hack saw blades won a bronze medal at the International Universal Exposition in Paris. Not content with operating a successful small business, William M. Pratt began an aggressive program of expansion.

The Massachusetts Tool Company formed

In 1900, William M. Pratt organized the Massachusetts Tool Company, a wholly owned subsidiary of Goodell-Pratt, for the purpose of manufacturing machinists’ and precision tools. The operation was capitalized at $25,000, and construction began almost immediately on a sixty-by-eighty-foot building on land leased from the Goodell-Pratt Company. Located next door to the G-P plant, Massachusetts Tool operated as a union shop, giving it an edge over competitors in situations where customers preferred a supplier with a unionized labor force. (At the time, competitors L. S. Starrett and Brown & Sharpe were non-union.) The strategy was not without its pitfalls—relationships between labor and management were prone to seesaw, and the right to display the union label could be withdrawn on short notice. Then too, the advantage of a union shop could be lost if a manufacturer’s competitors improved their labor practices and won union approval. Unable or unwilling to meet the standard union wage, Massachusetts Tool lost the right to International Association of Machinists label in 1910. An ambivalent L. S. Starrett Company lost and recovered the use of the label several times during the first dozen years of the twentieth century.(4)

In 1900, William M. Pratt organized the Massachusetts Tool Company, a wholly owned subsidiary of Goodell-Pratt, for the purpose of manufacturing machinists’ and precision tools. The operation was capitalized at $25,000, and construction began almost immediately on a sixty-by-eighty-foot building on land leased from the Goodell-Pratt Company. Located next door to the G-P plant, Massachusetts Tool operated as a union shop, giving it an edge over competitors in situations where customers preferred a supplier with a unionized labor force. (At the time, competitors L. S. Starrett and Brown & Sharpe were non-union.) The strategy was not without its pitfalls—relationships between labor and management were prone to seesaw, and the right to display the union label could be withdrawn on short notice. Then too, the advantage of a union shop could be lost if a manufacturer’s competitors improved their labor practices and won union approval. Unable or unwilling to meet the standard union wage, Massachusetts Tool lost the right to International Association of Machinists label in 1910. An ambivalent L. S. Starrett Company lost and recovered the use of the label several times during the first dozen years of the twentieth century.(4)

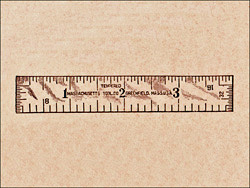

In 1901, Massachusetts Tool purchased the machinery, stock, patents, fixtures, and good will of the Coffin & Leighton Company, of Syracuse, New York. Coffin & Leighton manufactured a line of highly regarded, tempered steel rules based on United States Letters Patent No. 325,096 awarded to John Coffin & Herbert J. Leighton in 1885. The Leighton rules were noteworthy for the presence of extremely accurate gradations on both their narrow and long sides, markings which served to facilitate bi-directional measuring.

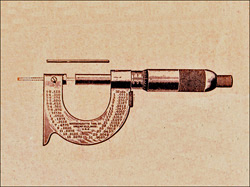

Massachusetts Tool added micrometers to its lineup the same year (1901) when it acquired the Lavigne Micrometer Company of New Haven, Connecticut. The Lavigne purchase came with the rights to a half dozen precision tool patents owned by company founder Joseph P. Lavigne. Certainly, the most interesting of these was United States Letters Patent No. 515234. Issued February 20, 1894, the patent covered a micrometer with a foot-like extension on the end of the frame opposite its adjustment screw. A steel rod inserted through a hole in its anvil allowed the device to function as a depth micrometer, a feature that allowed a machinist to avoid the purchase of a second tool. (Micrometer pictured below.)

The Massachusetts Tool Company fielded a line of products that included rules, micrometers, calipers, levels, gages, squares, and cutters. It published its own price list until 1909 when management added its tools to an expanded Goodell-Pratt catalog. When the Goodell-Pratt Company absorbed Massachusetts Tool in 1912, the smaller firm enjoyed a capitalization of $40,000.

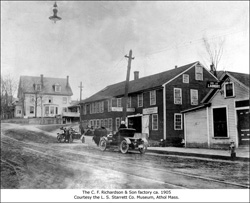

C. F. Richardson & Son

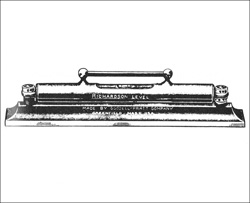

In 1904, Goodell-Pratt acquired the rights to a line of iron spirit levels manufactured by C. F. Richardson & Son, a small business based in Athol. As much a general machine shop as a factory, the operation was established by Nathaniel Richardson and passed on to his sons Charles F. and George H. Richardson after his death in 1883. Charles F. Richardson became sole proprietor in 1886 and brought his son, Frederick Ray, into the business about 1895. Located in a rundown, two-story frame building on the banks of the Millers River, an undershot wheel that took advantage of a two-to-three foot drop in the riverbed powered the operation. Never a large enterprise, employment in the 1890s averaged about twenty hands. In addition to manufacturing light-duty lathes, levels and transits, the shop did contract machining; sold and repaired bicycles and automobiles; and manufactured a prototype automobile of its own design. The bicycle and automobile sidelines reflected the interests of Fred R. Richardson who went on to active management of the company as his father turned his attention elsewhere. The Richardsons’ auto dealership sold an early steam-powered version of the Locomobile, the unsuccessful precursor to the famous Stanley Steamer.

In 1904, Goodell-Pratt acquired the rights to a line of iron spirit levels manufactured by C. F. Richardson & Son, a small business based in Athol. As much a general machine shop as a factory, the operation was established by Nathaniel Richardson and passed on to his sons Charles F. and George H. Richardson after his death in 1883. Charles F. Richardson became sole proprietor in 1886 and brought his son, Frederick Ray, into the business about 1895. Located in a rundown, two-story frame building on the banks of the Millers River, an undershot wheel that took advantage of a two-to-three foot drop in the riverbed powered the operation. Never a large enterprise, employment in the 1890s averaged about twenty hands. In addition to manufacturing light-duty lathes, levels and transits, the shop did contract machining; sold and repaired bicycles and automobiles; and manufactured a prototype automobile of its own design. The bicycle and automobile sidelines reflected the interests of Fred R. Richardson who went on to active management of the company as his father turned his attention elsewhere. The Richardsons’ auto dealership sold an early steam-powered version of the Locomobile, the unsuccessful precursor to the famous Stanley Steamer.

The company sold the rights to its iron levels to Goodell-Pratt when it consolidated with the Oliver & Whitney Company, an Athol-based manufacturer of machine screws. The new business, named the Richardson-Oliver Company, manufactured scientific equipment and machine tools. Located in Athol, the company was incorporated in Maine and capitalized at $10,000. It is likely that the proceeds of the sale of the line of metallic levels formed a substantial part of the Richardsons’ stake in the new operation.

The L. S. Starrett Company bought the C. F. Richardson line of transit levels the following year (1905). It was not the first time the family had done business with Laroy S. Starrett. Between 1878 and 1880, the Nathaniel Richardson machine shop had served as the original manufacturer of Starrett’s ground-breaking combination square. When Starrett’s former partners threatened a law suit, the Richardsons—fearing involvement—opted out of the arrangement. Starrett bought the stock and tooling, moved a few doors away and founded the L. S. Starrett Company, a business destined to become the country’s leading manufacturer of precision tools. In 1907, the Richardsons sold their machine shop building to L. S. Starrett. It was razed in 1910.(5)

Growth and construction

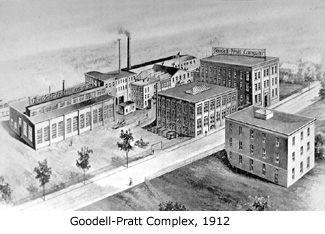

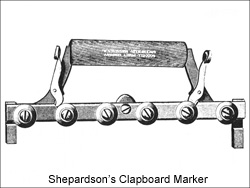

In 1903, the Goodell-Pratt started construction on an eighty-five by forty-three-foot three-story brick building to house its office and packing operation. Three years later, it contracted for another three-story warehouse of almost the same size.(6) The product line was growing—the operation's 1905 catalog contained forty-eight more pages and 100 more tools than the 1903 issue. The new catalog included the line of iron levels bought from C. S. Richardson in 1904, boxed tool sets for the home handyman and a unique clapboard marking gage patented by Greenfield resident Edward B. Shepardson. The 1907 catalog, 208 pages long, included fifty more tools than the 1905. The 1909 Goodell-Pratt catalog numbered 272 pages and included dozens of new tools. By 1912, the enterprise advertised that its product line included 1200 sizes and kinds of tools sold everywhere the sun shines.

In 1903, the Goodell-Pratt started construction on an eighty-five by forty-three-foot three-story brick building to house its office and packing operation. Three years later, it contracted for another three-story warehouse of almost the same size.(6) The product line was growing—the operation's 1905 catalog contained forty-eight more pages and 100 more tools than the 1903 issue. The new catalog included the line of iron levels bought from C. S. Richardson in 1904, boxed tool sets for the home handyman and a unique clapboard marking gage patented by Greenfield resident Edward B. Shepardson. The 1907 catalog, 208 pages long, included fifty more tools than the 1905. The 1909 Goodell-Pratt catalog numbered 272 pages and included dozens of new tools. By 1912, the enterprise advertised that its product line included 1200 sizes and kinds of tools sold everywhere the sun shines.

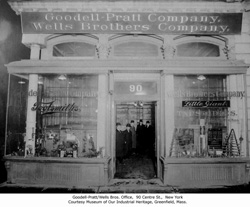

Not all the Goodell-Pratt Company's tools were manufactured on site. Albert D. Goodell's Goodell Tool Company of Shelburne Falls produced bit braces, butt gauges and glass cutters for the operation. In 1907, Goodell Tool incorporated and William M. Pratt bought a controlling interest in the business. As a result of his purchase, the Goodell-Pratt Company became sole distributor for the Goodell Tool Company's products, and Pratt's father, Francis, who lived in Shelburne Falls, became vice-president of the operation. Not one to burn bridges, William H. Pratt had no difficulty in teaming up with former employer, the Wells Brothers Company, when conditions warranted. The Goodell-Pratt Company would share a sales office with Wells Brothers at 90 Centre Street in New York sometime between the years 1910 and 1914. Located in the hardware district, the front windows of the building were emblazoned with the Goodell-Pratt Toolsmiths logo and the trademark for Wells Brothers’ Little Giant taps and dies.

Despite its growing and diverse array of products, the Goodell-Pratt Company purchased rough castings from an out-of-town supplier and hauled them from the local rail depot to its factory. The situation changed in 1910 when the enterprise opened a-state-of-the-art, reinforced concrete foundry. The facility measured seventy-five by 100 feet and included a twenty-one by fifty-four-foot pattern shop as well as walk-through access to the operation's thirty-five by forty-foot machine shop. The design eliminated the need for columns on the casting floor, creating a large open area for the men involved in the work. The open area was made possible by the use of concrete beams that spanned seventy-five feet, were five feet ten inches deep, and that supported the workroom's concrete roof. The reinforced concrete shell allowed for the installation of massive windows which flooded the area with natural light.(7)

The Ducharmes & Company, a small Shelburne Falls manufacturer of such small, hammer-forged tools as screwdrivers, awls, and punches, fell to William M. Pratt’s voracious appetite in 1912. The business was fairly new; it had been founded by Francis E. Ducharme and his son—also named Francis—around 1907. Since two of the principals shared the Ducharme name, the plural form, Ducharmes, was proudly adopted for the business. Francis Ducharme Sr. had a long acquaintance with the Pratt family. He had first moved to Shelburne Falls in 1861 to work in the axe manufactory of William Pratt's grandfather Josiah. After the ax shop closed, he went to work for H. H. Mayhew Company, the firm where William M. Pratt served as secretary and his father Francis R. Pratt as treasurer. The purchase of Ducharmes & Company formed the basis for a new entity, the Pratt Drop-Forge and Tool Company, a business in which one of the Francis Ducharmes became a director and the other superintendent. The creation of the Drop-Forge and Tool Company resulted in the discontinuation of the Ducharmes trademark.

With the infusion of Pratt capital, the Pratt Drop-Forge and Tool Company put up a new factory in 1913, on the Buckland side of the river, just north of Wellington Street. Like the Goodell-Pratt factory in Greenfield, the facility was built of reinforced concrete, a construction technique that sounded the death knell for brick and wood industrial structures. The new building measured forty by 100 feet, and an area of forty by forty was given over to the forge room. Citizens of Shelburne Falls welcomed the thirty jobs that accompanied the plant's opening. The Pratt Drop-Forge and Tool Company eventually became part of Goodell-Pratt, and its factory was renamed Goodell-Pratt Company Plant No. 2. At its peak, the operation employed sixty men, but when the Millers Falls Company took ownership of the factory as part of its purchase of Goodell-Pratt, it shuttered the factory. The building remained in use as of 2010, serving as the home of Mayhew Steel Products.(8)

With the infusion of Pratt capital, the Pratt Drop-Forge and Tool Company put up a new factory in 1913, on the Buckland side of the river, just north of Wellington Street. Like the Goodell-Pratt factory in Greenfield, the facility was built of reinforced concrete, a construction technique that sounded the death knell for brick and wood industrial structures. The new building measured forty by 100 feet, and an area of forty by forty was given over to the forge room. Citizens of Shelburne Falls welcomed the thirty jobs that accompanied the plant's opening. The Pratt Drop-Forge and Tool Company eventually became part of Goodell-Pratt, and its factory was renamed Goodell-Pratt Company Plant No. 2. At its peak, the operation employed sixty men, but when the Millers Falls Company took ownership of the factory as part of its purchase of Goodell-Pratt, it shuttered the factory. The building remained in use as of 2010, serving as the home of Mayhew Steel Products.(8)

The Stratton Level Company

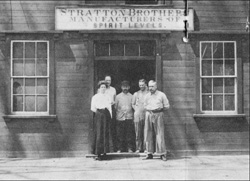

In 1912, Goodell-Pratt acquired the Stratton Level Company, a well-known manufacturer of carpenter’s and machinist’s spirit levels located in Greenfield. A local fixture since 1869, the company had been founded as Stratton Brothers by Edwin A. and Charles M. Stratton, Greenfield residents who'd spent most of their lives in the construction trades. When the brothers relocated to Springfield to work at the armory during the American Civil War, the experience convinced them that their future lay in manufacturing.

When work at the armory returned to peace-time levels, the Strattons returned home. It took them three years to develop a product and set up shop in a modest two-story building at 26 School Street. The operation was anything but plush; the building measured just 30 x 50 feet and was fitted with a mix of homemade machinery and second-hand equipment from the Springfield Armory. More interested in building levels than in financial success, the Strattons were hardly entrepreneurs. Though they built a top-notch product, the Strattons hesitated to invest in plant and equipment and remained stubbornly determined to restrict their output to spirit levels.

Though the company manufactured several grades of levels, its reputation rested on its premium models—fully brass-bound products with solid brass end plates and brass-trimmed side lights. The levels' brass-bound edges protected the edges of the expensive tropical woods used in their manufacture and helped prevent warping. So precise were the cuts for the square brass rods used for the binding, over one thousand pounds of pressure were required to force them into place.

The Strattons' levels sold well, and another Greenfield firm, the Millers Falls Company, became one of the firm's best customers. Millers Falls catalogs featured Stratton Brothers wooden levels from 1874 until almost 1890. Stratton levels reappeared in the catalog in the mid-1890s after the Millers Falls Company’s attempts to manufacture its own wooden levels came to naught. The Stratton levels remained in the Millers Falls catalogs through 1901. The end of the arrangement coincided with the sale of the Stratton Brothers Company in 1902.

The Stratton's youngest brother, Oscar, joined the business at some point. A machinist, he had plied his trade in Windsor, Vermont, and Springfield, Massachusetts, before returning to Greenfield to work at B. B. Noyes & Company, a general purpose foundry noted for manufacturing carriage parts. Though Oscar G. Stratton brought manufacturing experience to the operation, he did not become a partner. When Charles Stratton died in 1893, Oscar remained with the firm, and Edwin continued doing business as Stratton Brothers.

A family enterprise in every sense of the word, the Stratton Brothers production supervisor, Roland O. Stetson, was married to married Edwin's daughter. He bought the business from his eighty-three-year-old father-in-law in 1902. Six years later, after an attempt to re-brand the business as R. O. Stetson, he sought outside capital and incorporated the operation as the Stratton Level Company. Investor A. L. Richtmyre,(9) became company president and focused his efforts on management and sales, while Stetson served as treasurer and remained in charge of production. Stratton Level continued the Stratton Brothers tradition of manufacturing high-quality spirit levels, but soon found it necessary to expand its line of moderately priced models. The premium levels, labor intensive and manufactured from high-grade tropical hardwood, were expensive to produce and commanded a price beyond of reach of the average worker.

Stratton Level met its demise just four years after incorporation when William M. Pratt bought the company and moved production to the second floor of the Goodell-Pratt factory in Greenfield. Roland O. Stetson became a Goodell-Pratt employee, but continued tinkering with and repairing levels at the old Stratton Brothers plant on School Street. The acquisition of the Stratton Level Company brought a well-respected line of wooden levels to Goodell-Pratt—an addition that proved a nice complement to the metallic levels it had marketed since the acquisition of the C. F. Richardson line.(10)

Expansion and demise

In addition to its awls, bit braces, levels, miter boxes, breast drills, hand drills, push drills and screwdrivers, the company maintained a line of products that ranged from automotive tools to washer cutters. The main plant in Greenfield saw major expansions in 1913 and 1917, and during World War I, the Goodell-Pratt workforce reached an all-time high—740 employees.

In addition to its awls, bit braces, levels, miter boxes, breast drills, hand drills, push drills and screwdrivers, the company maintained a line of products that ranged from automotive tools to washer cutters. The main plant in Greenfield saw major expansions in 1913 and 1917, and during World War I, the Goodell-Pratt workforce reached an all-time high—740 employees.

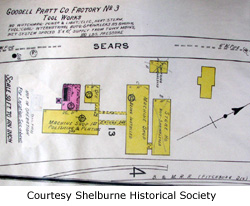

Albert Goodell, the founder of the Goodell Tool Company, died in 1915. Two years later, the Goodell-Pratt Company purchased the remainder of his smaller company. Since Albert Goodell had sold a controlling interest to Goodell-Pratt in 1907 and marketed his tools under the Goodell-Pratt trademark, the change had little effect on day-to-day operations. The new management unwound the affairs of Goodell Tool and changed the name of the factory to Goodell-Pratt Company Plant No. 3. It closed the aging facility in 1923 and transferred operations to the main plant in Greenfield. Goodell-Pratt added power tools to its line two years later when it acquired the electric drill operation of the A. F. Way Company, of Hartford, Connecticut.

The Goodell-Pratt Company became sole distributor of the Goodell Manufacturing Company's products when Henry E. Goodell retired from the operation in 1916. Goodell-Pratt had maintained a sizeable stake in Goodell Manufacturing since 1903, and when Henry Goodell died in 1923, William M. Pratt became the Manufacturing Company's president. In March 1930, the Goodell-Pratt Company purchased the remainder of the Goodell Manufacturing from Goodell's son-in-law Perley E. Fay and moved its equipment to the main Goodell-Pratt plant on Wells Street.(11)

Employing over 400 employees and maintaining a line of 1500 tools, Goodell-Pratt was unprepared for a catastrophic economic downturn. At the time of the 1929 stock market crash, the company operated three factories: two in Greenfield (the main plant and the Goodell Manufacturing Company) and one in Shelburne Falls (the former Pratt Drop-Forge and Tool Company, known as Plant No. 2). With the onset of the Great Depression, these measures of success translated into excess production capacity and a bloated product line. Once capitalized at 2.1 million dollars, Goodell-Pratt stock sank to a low of fifty cents a share in 1930. John W. Smead, a Millers Falls Company’s vice-president and an executive at Goodell-Pratt’s bank, understood the financials and considered Goodell’s stock undervalued. He acquired enough of the outstanding shares to force a merger, and in 1931 Goodell-Pratt became part of the Millers Falls Company.(12)

A skilled and ambitious businessman, William M. Pratt had erred in being too highly leveraged when economic catastrophe hit. The fortunes of his Goodell-Pratt Company unwound quickly, going from rosy to abysmal in just eighteen months. After the merger, he took a seat on the Millers Falls Company’s board of directors and served as an international sales representative. William Maynard Pratt died September 26, 1946. Millers Falls continued to use the Goodell-Pratt brand on selected tools until 1948 and featured both the Millers Falls and Goodell-Pratt trademarks on selected mailings as late as 1957.

Illustration credits

- William M. Pratt: A Century of experience: Millers Falls Company. Greenfield, Mass.: Greenfield Record, Gazette and Courier, August 13, 1968.

- H. H. Mayhew factory: Western New England. v. 2, no. 4, April 1912.

- Goodell-Pratt Company complex: Western New England. v. 2, no. 2, July 1912.

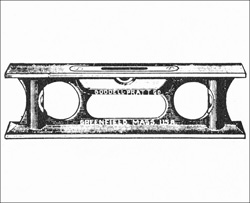

- Coffin & Leighton rule: Goodell-Pratt Company, Toolsmiths: Catalog Number 10. Greenfield, Mass.: Goodell-Pratt Company, 1911.

- Herbert J. Leighton portrait: Notable Men of Central New York: Syracuse and Vicinity, Utica and Vicinity, Auburn, Oswego, Watertown, Fulton, Rome, Oneida, Little Falls. S. l.: Dwight J. Stoddard, 1903.

- Lavigne micrometer: Goodell-Pratt Company, Toolsmiths: Catalog Number 10. Greenfield, Mass.: Goodell-Pratt Company, 1911.

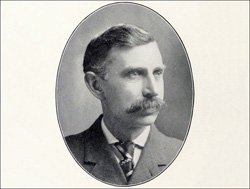

- Charles F. Richardson portrait: Men of Massachusetts: a Collection of Portraits of Representative Men in Business and Professional Life in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Boston: Boston Press Club, 1903.

- Richardson factory: Courtesy of the L. S. Starrett Company museum. This photograph of the original is copyright of the author.

- Richardson levels: Tools Manufactured by Goodell-Pratt Company: Catalog No. 7. Greenfield, Mass.: Goodell-Pratt Company, 1905.

- New York City Wells Bros./Goodell-Pratt office: Courtesy of the Museum of Our Industrial Heritage. This photograph of the original is copyright of the author.

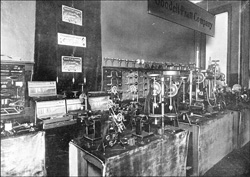

- Goodell-Pratt in-store displays: Western New England. v. 2, no. 2, July 1912.

- Goodell-Pratt foundry: "A Reinforced Concrete Foundry." Foundry News. v. 1, no. 1, May 1910.

- Ducharmes trademark: Goodell-Pratt Company, Toolsmiths: Catalog Number 11. Greenfield, Mass.: Goodell-Pratt Company, 1913.

- Edwin A. Stratton portrait: Biographical Review: Sketches of the Leading Citizens of Franklin County, Massachusetts. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company, 1895.

- Stratton Brothers Factory: "Stratton Levels." The Mechanick's Workbench. No. 6, December 1978.

- Goodell-Pratt Plant No. 2: Goodell-Pratt Company, Toolsmiths: Complete Catalog No. 17. Greenfield, Mass.: Goodell-Pratt Company, 1930.

- Map of Goodell-Pratt factory No. 3: Sanborne Map Company. Shelburne Falls, Franklin County, Massachusetts, December 1919. Copy updated by Sanborne in 1933 with glued-on overlays. (Courtesy Shelburne Historical Society, Shelburne Falls, Mass.)

References

- On the Pratt family: Biographical Review: Sketches of the Leading Citizens of Franklin County, Massachusetts. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company, 1895. p. 61-62; Kenneth Cope. “Sorting out the Goodell companies.” Chronicle of the Early American Industries Association, v. 45 no. 4, p. 115; Genealogical and Personal Memoirs Relating to the Families of the State of Massachusetts. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1910. v. 3, p. 1549; National Cyclopedia of American Biography: Being the History of the United States as Illustrated in the Lives ... v. 41. Reprint ed. Ann Arbor, Mich.: University Microfilms, 1967. p. 265-266.

- United States Letters Patent No. 6,989X.

- "Josiah Pratt." Greenfield Courier and Gazette, May 23, 1887, p.1; MHC Reconnaissance Survey Town Report: Charlemont. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Commission, 1982. p.6; Historic & Archaeological Resources of the Connecticut River Valley: a Framework for Preservation Decisions. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Commission, 1984. p. 269; Josiah Gilbert Holland. History of Western Massachusetts: the Counties of Hampden, Hampshire, Franklin, and Berkshire ... Vol. 2. Springfield, Mass.: S. Bowles & Company, 1855. p. 427.

- Union shop information: Paul Jenkins. The Conservative Rebel: a Social History of Greenfield, Massachusetts. Greenfield, Mass.: Town of Greenfield, 1982. p. 183; “On Label Shops.” Machinists Monthly Journal, v. 23 (October 1911). p. 975; Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor. Annual Report of the Bureau of Statistics of Labor. Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co., 1906. p. 379; “Discards Union Label.” The Review (Detroit, Michigan: National Founders’ Association), (November 1911). p. 15.

- Kenneth L. Cope. Makers of American Machinist's Tools: a Historical Directory of Makers and Their Tools. Mendham, N. J.: Astragal Press,1994. p. 73, 241.

- "Greenfield Items." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) May 5, 1903, p. 6.; "Goodell-Pratt Co. Enlarging." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) August 25, 1906, p. 5; "Factories are All Hustling." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) November 17, 1906, p. 2.

- "A Reinforced Concrete Foundry." Foundry News. v.1, no.1 (May 1910). p. 4-5.

- Fannie Shaw Kendrick. The History of Buckland. Buckland, Mass.: Town of Buckland, 1937. p. 253; "New Shop Will Start with 30 Men." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) August 7, 1912, p. 6; "Celebrated 50th Anniversary." Gazette and Courier (Greenfield, Mass.) November 19, 1913, p. 2.

- At times, erroneously reported as O. L. Richtmyre. A. L. Richtmyre became president of Stratton Level Company after working for the Boston & Maine Railroad. See: "Trade Notes." Iron Trade Review. v. 42, no. 9 (February 28, 1908). p. 432.

- Most of the information in section: Don Wing. "Stratton Levels." The Mechanick's Workbench. No. 6 (December 1978). p. 8-9.

- Kenneth Cope. “Sorting out the Goodell Companies.” Chronicle of the Early American Industries Association, v. 45, no. 4 (December 1992). p. 115.

- Smead’s role: Paul Jenkins. The Conservative Rebel: a Social History of Greenfield, Massachusetts. Greenfield, Mass.: Town of Greenfield, 1982. p. 183.