Featured Braces

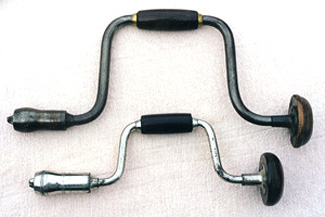

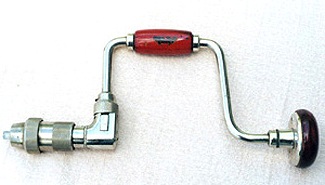

The Barber Brace

On May 24, 1864, William Henry Barber, a Greenfield, Massachusetts, native who had been working in Windsor, Vermont, was issued United States Letters Patent No. 42,827 for a holder of bits and other small tools. The holder described in the patent consisted of a rotating shell that enclosed a pair of spring-loaded, adjustable jaws. Although there were other adjustable chucks on the market, the simplicity and flexibility of the Barber chuck would quickly position it to become the standard in bit holding technology. Charles Amidon and Levi Gunn, partners who were to become principals in the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company, purchased Barber’s patent in 1865 and began building a wrought iron brace featuring the new chuck. The partners’ brace had a huge advantage over those of their competitors due to its unparalleled ability to securely hold bits with tapered, square shanks. The reputation of the Barber Brace spread quickly; tens of thousands were sold, and its profitability became the foundation on which the Millers Falls Mfg. Company was built. The firm

continued to build braces with jaws in Barber’s original style until the early 1920s. The brace seen here was manufactured in the mid-1860s.

On May 24, 1864, William Henry Barber, a Greenfield, Massachusetts, native who had been working in Windsor, Vermont, was issued United States Letters Patent No. 42,827 for a holder of bits and other small tools. The holder described in the patent consisted of a rotating shell that enclosed a pair of spring-loaded, adjustable jaws. Although there were other adjustable chucks on the market, the simplicity and flexibility of the Barber chuck would quickly position it to become the standard in bit holding technology. Charles Amidon and Levi Gunn, partners who were to become principals in the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company, purchased Barber’s patent in 1865 and began building a wrought iron brace featuring the new chuck. The partners’ brace had a huge advantage over those of their competitors due to its unparalleled ability to securely hold bits with tapered, square shanks. The reputation of the Barber Brace spread quickly; tens of thousands were sold, and its profitability became the foundation on which the Millers Falls Mfg. Company was built. The firm

continued to build braces with jaws in Barber’s original style until the early 1920s. The brace seen here was manufactured in the mid-1860s.

On June 22, 1880, Henry L. Stevens, a company employee, was issued United States Letters Patent No. 229,197 for adding to Barber’s jaws “a hollow cylinder... applied upon the spring to retain it and to hold [it] in a steady and even position to [the] jaws of a bit brace.” The Millers Falls Company adopted Stevens’ idea and, for a time, stamped notice of the patent date on the shells of its Barber type braces. The date marked on the braces, June 23rd, is one day after that of the actual issue of the patent. The Stevens patent was just one of a number of improvements that the company made to the basic Barber Brace over the years. The most significant change came fairly early in the game, in 1868, when Charles Amidon’s “Barber Improved” jaws were incorporated into the product line. The company was to offer braces featuring both Amidon’s and Barber’s jaws for decades.

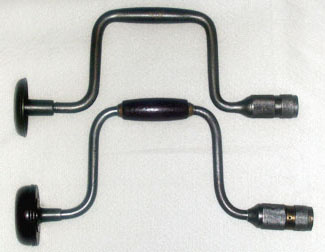

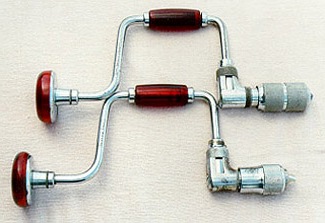

The Barber Improved Brace

Charles Amidon may have had more to do with the overwhelming success of the Barber Brace than William H. Barber. In addition to recognizing, along with Gunn, the commercial potential of the brace, Amidon developed a set of jaws far superior to those designed by Barber. It is interesting to note that more Barber braces were sold with Amidon’s jaws than were ever equipped with Barber’s.

Charles Amidon may have had more to do with the overwhelming success of the Barber Brace than William H. Barber. In addition to recognizing, along with Gunn, the commercial potential of the brace, Amidon developed a set of jaws far superior to those designed by Barber. It is interesting to note that more Barber braces were sold with Amidon’s jaws than were ever equipped with Barber’s.

The design for Amidon’s springless jaws was simplicity itself. The two identical jaws ride on a simple steel pin and are adjustable to various sizes of square and rectangular shanks. In addition to being inexpensive to manufacture and assemble, the jaws maintain contact with a bit along their full length, affording an extremely secure hold on a variety of bits. Millers Falls marketed braces equipped with Amidon’s jaws as Barber Improved Braces. During the first decade of the twentieth century, Amidon’s jaws were phased out, replaced by various self-opening and alligator-type jaws. The designations “Barber” and “Barber Improved” ceased to have any real meaning by the mid-1920’s as the term Barber had become a generic identifier used to refer to any of the company’s standard braces with alligator jaws.

The braces shown above are part of the No. 10-16 series. The series anchored the company’s line of non-ratcheting, Barber Improved Braces for a half century. The larger, heavy duty brace is the earlier of the two. Both tools feature Samuel Sawyer's patented design for attaching a head to a brace, and both are equipped with a rotating wrist handle designed by William H. McCoy. McCoy's wrist handle was equipped with metal ring inserts which prevented its splitting and facilitated its rotation. The men were issued patents for their designs on August 15, 1871.

Amidon’s eyebolt brace

Charles Amidon, one of the founders of Millers Falls Manufacturing, was a prolific designer who would register at least a dozen patents relating to the woodworker’s brace. The patent covering the brace shown here was issued in 1867, the year before that for his improvement to Barber’s chuck and the founding of the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company. The brace’s bit-holding design is simple. A wing nut screws onto an eyebolt with a square hole in it. A bit inserted into the hole is pulled against the brace stock as the nut is tightened, locking the bit in place. The brace shown at top is unmarked, as was much of the output of Gunn, Amidon & Company. It dates from the 1860s, and its head is manufactured of domestic hardwood. The profile of the head is characteristic of that used by Gunn & Amidon as well as the earliest output of the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company.

Charles Amidon, one of the founders of Millers Falls Manufacturing, was a prolific designer who would register at least a dozen patents relating to the woodworker’s brace. The patent covering the brace shown here was issued in 1867, the year before that for his improvement to Barber’s chuck and the founding of the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company. The brace’s bit-holding design is simple. A wing nut screws onto an eyebolt with a square hole in it. A bit inserted into the hole is pulled against the brace stock as the nut is tightened, locking the bit in place. The brace shown at top is unmarked, as was much of the output of Gunn, Amidon & Company. It dates from the 1860s, and its head is manufactured of domestic hardwood. The profile of the head is characteristic of that used by Gunn & Amidon as well as the earliest output of the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company.

The brace seen directly beneath it was made in the 1870s by the Millers Falls Mfg. Company. It features a lignum vitae head attached to its frame by means of Samuel Sawyer’s design. Amidon's eyebolt brace was a slow seller and was dropped from the catalog sometime prior to 1878.

Charles H. Amidon left Millers Falls Mfg. in early 1870 to manufacture baby carriages and, later on, bit braces. His business, the Amidon Manufacturing Company, was located next to the Millers Falls factory and relied on water power supplied by his former business partners. Amidon’s business went bankrupt in 1877, due, in large part, to a disastrous fire a year earlier. Charles Amidon moved on to Buffalo, New York, where he became involved in a succession of brace-manufacturing enterprises. Information on his post-Millers Falls patents can be found at the Charles H. Amidon Later Braces Gallery.

The Rose Brace

Clemens B. Rose, of Sunderland, Massachusetts, a village about a dozen miles from Greenfield, was the holder of a half dozen patents relating to braces and bit stocks. The most significant of these was awarded on April 16, 1867, when he received patent protection for a ring-type chuck and for a method of attaching a metallic head to a brace. Rose was issued yet another patent a year and a half later for an improvement in attaching wooden sweep handles to the frames of braces. The patent for the handle included a provision that the manufacturers of the Rose Brace never exploited—it allowed for the sweep handle to be attached in a rotating manner.

Clemens B. Rose, of Sunderland, Massachusetts, a village about a dozen miles from Greenfield, was the holder of a half dozen patents relating to braces and bit stocks. The most significant of these was awarded on April 16, 1867, when he received patent protection for a ring-type chuck and for a method of attaching a metallic head to a brace. Rose was issued yet another patent a year and a half later for an improvement in attaching wooden sweep handles to the frames of braces. The patent for the handle included a provision that the manufacturers of the Rose Brace never exploited—it allowed for the sweep handle to be attached in a rotating manner.

The top brace in the illustration at right features all three patents. It was manufactured by the Bit Stock Company, a Greenfield firm owned by William Newton Nims and an unidentified Mr. Pratt. By spring of 1869, the partnership of Nims & Pratt was in firm control of the Rose patents, and several months later, ownership passed on to Millers Falls Manufacturing. Henry Pratt, one of the founders of Millers Falls Manufacturing, petitioned to have the patent reissued in 1873 in the hope of increasing the protections afforded by it. The lower of the two braces features Rose’s chuck, but it is equipped with a lignum vitae head attached to its frame by means of Samuel Sawyer’s design and features a rotating sweep handle courtesy William McCoy’s patent. By 1878, Millers Falls was no longer marketing braces with the Rose chuck.

An early variant of this brace with its chuck forged in place and a forged sweep is known. Produced by Clemens Rose prior to his 1868 patent for a sweep handle, some examples bear the stamp "Rose's Pat."

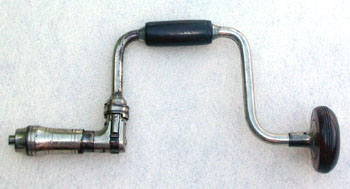

The Goodell Brace

In 1870, the Millers Falls Mfg. Company purchased a small factory operated by Albert D. and Henry E. Goodell. The men, brothers, had started the operation, at Buckland, Massachusetts, in 1866. Their enterprise originally made pieces for wooden chairs but switched to hardware items in 1868—the year that Albert was issued a patent for a brace with a ring-type chuck and pivoting jaws. The two men became employees of Millers Falls Manufacturing at the time of the sale, and their new employer took on production of the Goodell Brace. Albert Goodell went on to become plant superintendent and embarked on a distinguished career in tool design and manufacture—developing a number of highly successful tools for the Millers Falls Company before leaving, in 1888, to found Goodell Brothers with his brother Henry.

In 1870, the Millers Falls Mfg. Company purchased a small factory operated by Albert D. and Henry E. Goodell. The men, brothers, had started the operation, at Buckland, Massachusetts, in 1866. Their enterprise originally made pieces for wooden chairs but switched to hardware items in 1868—the year that Albert was issued a patent for a brace with a ring-type chuck and pivoting jaws. The two men became employees of Millers Falls Manufacturing at the time of the sale, and their new employer took on production of the Goodell Brace. Albert Goodell went on to become plant superintendent and embarked on a distinguished career in tool design and manufacture—developing a number of highly successful tools for the Millers Falls Company before leaving, in 1888, to found Goodell Brothers with his brother Henry.

The Goodell Brace seen on the lower left was built in the 1870s by the Millers Falls Mfg. Company. It features a brass and steel chuck and is equipped with a rotating sweep handle courtesy William McCoy’s patent. Its lignum vitae head is attached to its frame by means of Samuel Sawyer’s design. The brace seen above it features a metallic head and is stamped on the frame with the words “Mechanics Brace.” (At the time, skilled carpenters and machinists were considered mechanics.) The chucks of the earliest Goodell Braces were composed entirely of wrought iron and steel; a slight swelling of the frame served as a sweep handle. The Goodell Brace was slow to catch on, and it was dropped from the catalog sometime prior to 1878.

Dolan’s ratchet patent

On January 17, 1871, William P. Dolan (also spelled Dolin) of Charlottesville, Virginia, patented a ratcheting brace that allowed the user to bore a hole without completing a full rotation of the handle. His ratchet braces made it possible to make holes in the numerous situations where an obstruction prevents the use of a standard brace. Although Dolan’s was not the first ratchet brace, his use of two opposing, spring-loaded pawls to control the direction of a bit brace’s rotation was a breakthrough. Millers Falls made substantial changes to his design—substituting one ratchet wheel for Dolan’s

two and adding a ring shifter to engage and disengage the pawls.

On January 17, 1871, William P. Dolan (also spelled Dolin) of Charlottesville, Virginia, patented a ratcheting brace that allowed the user to bore a hole without completing a full rotation of the handle. His ratchet braces made it possible to make holes in the numerous situations where an obstruction prevents the use of a standard brace. Although Dolan’s was not the first ratchet brace, his use of two opposing, spring-loaded pawls to control the direction of a bit brace’s rotation was a breakthrough. Millers Falls made substantial changes to his design—substituting one ratchet wheel for Dolan’s

two and adding a ring shifter to engage and disengage the pawls.

The Millers Falls adaptation of Dolan’s idea, with its two-pin ring shifter, may well have been the most significant development in the history of the American ratchet brace. The design, which leaves the front part of the ratchet wheel exposed, came to be used on more braces than any other and remains in production today.

The brace shown at right, manufactured about 1880, features a chuck shell stamped with the Dolan’s patent date.

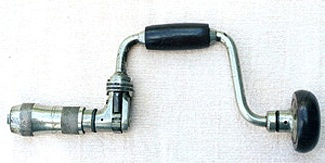

Lynam’s Ratchet Patent

Four months after the Dolan patent was issued, John T. Lynam of Jeffersonville, Indiana, was issued a patent for a single ratchet wheel brace that used leaf springs as pawls. Lynam’s design incorporates an eccentric cam attached to a thumbscrew that pushes the springs away from the ratchet wheel as it is rotated. While the arrangement allows for ratcheting in clockwise and counterclockwise directions, it lacks a feature common to most ratchet braces—a true center lock that turns off the ratcheting feature.

Four months after the Dolan patent was issued, John T. Lynam of Jeffersonville, Indiana, was issued a patent for a single ratchet wheel brace that used leaf springs as pawls. Lynam’s design incorporates an eccentric cam attached to a thumbscrew that pushes the springs away from the ratchet wheel as it is rotated. While the arrangement allows for ratcheting in clockwise and counterclockwise directions, it lacks a feature common to most ratchet braces—a true center lock that turns off the ratcheting feature.

Lynam’s foray into bit brace design was short-lived as his primary interest was in the development of agricultural equipment. His specialty was the design of grain drills, and his name appears on several patents for the devices that were issued between 1868 and 1877. Although the Millers Falls Company had enough confidence in Lynam’s ratchet brace to begin manufacturing and marketing it, the brace—with its lack of a reliable ratchet lock—never caught on.

The brace seen here was produced by the Millers Falls Manufacturing Company between 1871 and 1873. Production continued until ca. 1881. The Lynam brace featured Amidon’s jaws and Samuel Sawyer’s patented head attachment.

The Barber Improved Ratchet Brace

Dolan’s patent and Amidon’s jaws became the basis for the company’s Barber Improved Ratchet Brace. For nearly sixty years, the Barber Improved ratcheting line was anchored by the premium quality No. 30-34 series. The example seen here dates from the 1890s. Its cocobolo head rides on ball bearings and no longer displays the decorative beading typical of earlier M-F braces. (Cheaper braces were to lack the ball bearing feature for some time to come.) The brace also features William H. McCoy’s self-opening jaws. McCoy, the developer of the company’s non-splitting sweep handle, was issued a patent on February 18, 1890, for adding a spring to Amidon’s jaws. McCoy’s jaws were to be featured on a number of the company’s braces manufactured in the 1890s and early 1900s.

Dolan’s patent and Amidon’s jaws became the basis for the company’s Barber Improved Ratchet Brace. For nearly sixty years, the Barber Improved ratcheting line was anchored by the premium quality No. 30-34 series. The example seen here dates from the 1890s. Its cocobolo head rides on ball bearings and no longer displays the decorative beading typical of earlier M-F braces. (Cheaper braces were to lack the ball bearing feature for some time to come.) The brace also features William H. McCoy’s self-opening jaws. McCoy, the developer of the company’s non-splitting sweep handle, was issued a patent on February 18, 1890, for adding a spring to Amidon’s jaws. McCoy’s jaws were to be featured on a number of the company’s braces manufactured in the 1890s and early 1900s.

Millers Falls soon began to manufacture a toothed version of the jaws. The development was not patentable but served as the basis for the spring-type alligator jaws that were to characterize much of the operation’s later manufacture. The toothed jaws cost a bit more to produce so were initially used for premium braces—a development that relegated McCoy’s original design to the intermediate part of the line. Referred to as plain jaws near the end of their production history, the toothless version of McCoy’s design disappeared from the company’s offerings at roughly the same time that Amidon’s jaws were replaced by springless alligator jaws.

The No. 30-34 series was originally designed as a Barber Brace and fitted with Barber’s jaws. Equipped with Amidon’s chuck by 1885, the series was re-designated a Barber Improved Brace and retained that title when McCoy’s jaws were added in the 1890s. The No. 30-34 series lost its position as the top-of-the-line ratcheting brace when the Holdall Brace was introduced added to the lineup.

The Holdall Brace

On June 25, 1907, John A. Leland received a patent for a bit holding mechanism capable of maintaining contact with square, round, and tapered shanks throughout the length of its floating jaws. The result was a firm, well-aligned grip on the bit. Leland assigned the patent to the Millers Falls Company. Rather than upgrading the chuck on any of its existing series when the new jaws were introduced, Millers Falls created a new brace and called it the Holdall in order to draw attention the flexibility of the mechanism. In addition to the quality evidenced by Leland’s universal jaws, the Holdall Brace featured the ball bearing head and fully enclosed ratchet typical of premium ratchet braces at the time. Fully enclosed ratchets, sometimes referred to as fully-boxed, had begun to appear on the better braces in the M-F line in the 1890s—replacing traditional, partially enclosed half-boxed ratchets. Shortly after the introduction of the Holdall Brace, Millers Falls introduced a series of braces in which the ratchet dogs themselves were not visible and referred to the arrangement as a concealed ratchet.

On June 25, 1907, John A. Leland received a patent for a bit holding mechanism capable of maintaining contact with square, round, and tapered shanks throughout the length of its floating jaws. The result was a firm, well-aligned grip on the bit. Leland assigned the patent to the Millers Falls Company. Rather than upgrading the chuck on any of its existing series when the new jaws were introduced, Millers Falls created a new brace and called it the Holdall in order to draw attention the flexibility of the mechanism. In addition to the quality evidenced by Leland’s universal jaws, the Holdall Brace featured the ball bearing head and fully enclosed ratchet typical of premium ratchet braces at the time. Fully enclosed ratchets, sometimes referred to as fully-boxed, had begun to appear on the better braces in the M-F line in the 1890s—replacing traditional, partially enclosed half-boxed ratchets. Shortly after the introduction of the Holdall Brace, Millers Falls introduced a series of braces in which the ratchet dogs themselves were not visible and referred to the arrangement as a concealed ratchet.

Leland redesigned his chuck in 1909, replacing its coil spring with a bow spring and simplifying its construction. The new design was astonishing in its effectiveness. The brace shown here is an example of much later production and was manufactured long after the company had ceased referring to its chuck as the Holdall. It is a later model equipped with a steel-clad head. The steel-clad head—a wooden head on an oversized mounting plate—brought no additional functionality to a brace and solved no long-standing shortcomings in design. Its primary advantage was that of giving the tool a more finished appearance and providing additional surface area for shiny nickel plating. Leland patented yet another improvement to his universal jaws on May 30, 1916. His jaws were used on the firm’s better bit braces until 1957, when cheaper, less durable universal jaws became the order of the day. The distinctive orange color the example's wooden parts is the result of using orange varnish stain over light-colored tropical hardwood, a technique that the company employed to good effect. Earlier Holdall Braces featured cocobolo heads, and the trailing edge of the chuck shell exhibited a more rounded appearance than that of the brace shown here.

The Lion Brace

Millers Falls introduced one of its best-designed braces in 1914. The distinguishing feature of the new brace was the outstanding Lion chuck. The Lion is a ball bearing chuck with a large turned ring that provides for a better grip when adjusting its set of Leland’s universal jaws. The better grip, in turn, allows for more pressure

to be applied to any shank which is inserted into it. For this reason, the Lion chuck was also featured on the Millers Falls Company’s whimble brace, a heavy duty workhorse often used in bridge construction and in drilling beams. Believing that you can never have too much of a good thing, the company introduced a series of Lion Braces with octagonal shells in 1929. Although the octagonal shell allowed the user to exert even more pressure on a shank, there was little to be gained from over-tightening the jaws, and after a half dozen years, the octagonal models were abandoned. The Lion Brace was identical to the Holdall save for its chuck.

Millers Falls introduced one of its best-designed braces in 1914. The distinguishing feature of the new brace was the outstanding Lion chuck. The Lion is a ball bearing chuck with a large turned ring that provides for a better grip when adjusting its set of Leland’s universal jaws. The better grip, in turn, allows for more pressure

to be applied to any shank which is inserted into it. For this reason, the Lion chuck was also featured on the Millers Falls Company’s whimble brace, a heavy duty workhorse often used in bridge construction and in drilling beams. Believing that you can never have too much of a good thing, the company introduced a series of Lion Braces with octagonal shells in 1929. Although the octagonal shell allowed the user to exert even more pressure on a shank, there was little to be gained from over-tightening the jaws, and after a half dozen years, the octagonal models were abandoned. The Lion Brace was identical to the Holdall save for its chuck.

The Lion Brace pictured here dates from the 1950’s. By this time, the company had slightly modified the original profile of the chuck. The Lion Brace remained in production for over sixty years, many consider it to be the best user brace that the company ever manufactured.

The Parsons De Luxe Brace

In 1938, the Millers Falls Company introduced one of the finest braces ever mass produced. The brace, shown at top left, was designed by William J. Parsons, the “dean” of the design and engineering staff, to celebrate his fiftieth anniversary with the company. The Model 5010 Parsons De Luxe Brace features a full ball bearing chuck with Leland’s universal jaws.

In 1938, the Millers Falls Company introduced one of the finest braces ever mass produced. The brace, shown at top left, was designed by William J. Parsons, the “dean” of the design and engineering staff, to celebrate his fiftieth anniversary with the company. The Model 5010 Parsons De Luxe Brace features a full ball bearing chuck with Leland’s universal jaws.

The ratchet is fully boxed; the handle floats on oilite bronze bearings. The head also runs on an oilite bearing but features a full thrust bearing as well. The transparent red plastic (permaloid) heads and handles used on these braces have been extremely durable. The plastic on most examples looks much as it did some seventy-five years ago.

A permaloid head and handle do not necessarily a Parsons Brace make. The lower brace in the picture lacks the Parsons marking—even though it has permaloid components and bears the model number 5010C. The chuck on this model is decidedly inferior to that on the Parsons Brace. The large screw holding the ratchet assembly is exposed, rather than enclosed. The shell is shorter, displays less knurling is equipped with economy-type universal jaws.

Permaloid-handled braces were dropped from the product line in 1967.

The “Buck Rogers” Brace

When Millers Falls introduced a brace featuring red tenite handles in late 1949 or early 1950, it was numbered—appropriately enough—the Model 1950. The brace was a mid-range product selling for about half the price of the Parsons Brace. The handles and knobs are fabricated from Tennessee Eastman tenite #2 and were guaranteed unbreakable in use.

When Millers Falls introduced a brace featuring red tenite handles in late 1949 or early 1950, it was numbered—appropriately enough—the Model 1950. The brace was a mid-range product selling for about half the price of the Parsons Brace. The handles and knobs are fabricated from Tennessee Eastman tenite #2 and were guaranteed unbreakable in use.

Since the introduction of the No. 1950 coincided with that of the company’s radically designed, red plastic-appointed drills, saws and planes, it has become known as one of the Buck Rogers tools. Save for its plastic handles, however, the appearance of the Model 1950 was entirely traditional and virtually identical to most of the other half-boxed ratchet braces on the market at the time.

The No. 1950 was nickel plated, equipped with toothless alligator jaws and available only with the standard ten inch sweep. The brace was manufactured through at least 1981 with some of the later production sporting plastic ring shifters.