Snell Manufacturing Company

The Ware works

In the early 1790s, Thomas Snell, a son of Polycarpus Snell, moved from Bridgewater to Ware, Massachusetts. There he bought a 135-acre farm and set up a blacksmith shop on Flat Brook, a tributary of the Ware River. One of the earlier auger makers, he has been called the inventor of the twist auger and the bight auger. It is unlikely he invented either. The twist auger was almost certainly the double-twist auger already well-known in Pennsylvania. The meaning of the term "bight auger" has been lost to time, though it could refer to putting a lead screw on the tip of an auger, an idea pioneered by Henry Rauch of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.(1) What we do know of Thomas Snell's augers is that they “were made of iron with just enough steel welded to the end to make the cutting part. They were called steel-cut augers.”(2)

Thomas Snell initially shipped his augers in wooden boxes. The number of items in each container was determined by the diameters of the augers included. A box was considered full when the sum of the diameters of the individual augers reached 100 inches. Snell is reported to have hauled his augers to Boston for sale and returned to Ware with loads of steel, iron, and supplies.(3) The trips would have been major events. Given that a heavily loaded wagon might make ten to twelve miles a day, the seventy-odd-mile trek would have taken a week in each direction. As the years passed and roads improved, Snell's augers became more widely available. An 1828 newspaper ad placed by Greenfield, Massachusetts, merchandisers Gould & Ames reveals that his augers sold in the western part of the state as well.(4)

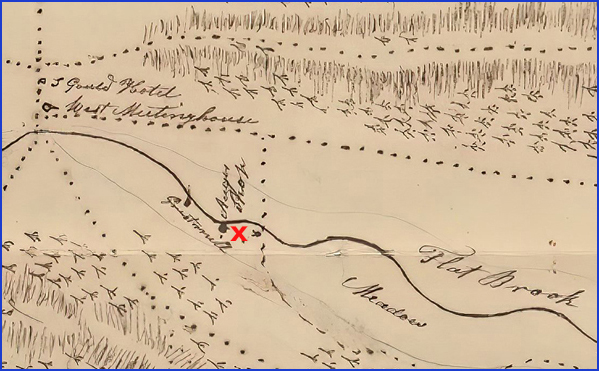

A manuscript surveyor's map dated 1830 shows Thomas Snell's Flat Brook auger shop located a mile above Ware's West Meeting House and the Seth Gould Hotel.(5) At its height, the works employed twenty workers, some of whom must have been family, for the elder Snell fathered seventeen children and at least three of them went into the auger-making business. When Thomas Snell died in 1833 at age sixty-one, his son Melville took over the operation. Another of Thomas Snell's sons, Deacon Thomas Snell, set up an auger-making shop at the site of a former gristmill a few hundred years downstream from his brother. In 1839 the value of the augers produced in Ware was estimated to be $4,500, the equivalent of $139,123.59 in 2023 dollars. Presumably most, if not all, of them originated in the Snell shops.(6)

In 1839 Melville Snell moved to North Providence, Rhode Island, where he manufactured augers and bits for two years and then relocated to Sturbridge, Massachusetts, ca. 1841. Deacon Thomas Snell continued making augers at the lower shop in Ware until 1854.

Relocation to Sturbridge

Melville Snell set up an auger shop in Sturbridge at Wight Village, a small settlement that had grown up around a mill site developed by Alpheus Wight at the end of the 18th century. One of Snell's nephews, Otis Snell, a son of Deacon Thomas Snell, moved to Sturbridge shortly afterward and joined him—whether as a partner or employee remains unclear, though an auger marked Snell, Towne & Snell is said to have surfaced. In 1845, Melville Snell partnered with Lauriston Towne and Judson Smith to set up an expanded auger-making operation in Wright Village in a vacant fulling mill. The new business operated as Towne, Snell & Company.(7)

Lauriston Towne left the business in 1846, Melville Snell and Judson Smith reorganized to become Smith, Snell & Company.(8) Towne went on to build a steam-powered brick factory, organized a business known as Towne, Chaffee & Company, and began producing augers on his own. Towne and Chaffee made augers for just four years. In 1851, the owners converted the factory into a planing mill and began producing dimensional lumber.(9)

Augustine Snell, a brother to Otis, relocated to Sturbridge from Ware in 1847. Just twenty-one years old, he joined Smith, Snell & Company as an employee and stuck with the Snell operation through its various reorganizations until his death in 1899. A third brother, Lucius, moved to Sturbridge in 1850. On his arrival, Lucius Snell bought Judson Smith's shares in Smith, Snell & Company. Otis Snell became a partner in the reorganized firm, and the business was reorganized as Snell & Brothers.

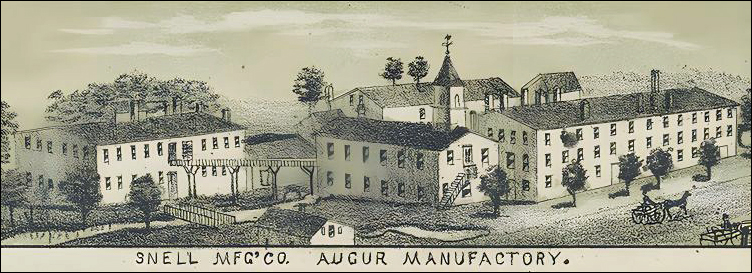

Snell & Brothers lost its factory in 1852 when a fire destroyed the mill that housed the operation. The operation moved to temporary quarters in the brick factory, built by Towne, Chaffee & Company in 1847. Residents of Sturbridge, concerned about the potential loss of the village's major employer, raised $770 to persuade the Snells to rebuild the factory.(10) Just how influential their efforts were is unknown, but the following year Snell & Brothers bought the Wight family mill site and its water-power rights. They moved the former Alpheus Wight gristmill seventy yards to the east and built a new two-story mill with a footprint of 32 x 100 feet. The relocated gristmill became the operation's office and packing room. Two stone mills followed in 1853: one 36 x 46 feet and featuring the company bell tower, the other 45 x 100 feet and three stories tall.

In 1854 Deacon Thomas Snell moved from Ware to Sturbridge to become a partner in Snell & Brothers. Seventy-five people now worked for the business. Wanting to keep their employees close at hand, the partners laid out Snell and Auger streets and built worker housing. Locals soon began to refer to the neighborhood near the plant as Snellville. Though the bulk of the business's production was comprised of gimlets, scotch-lip augers, and double-spur auger bits, Snell Brothers also operated a sawmill.

All looked good until 1857, the year Otis Snell, the firm's financial manager died, and the failure of the New York Branch of the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company started a run on the nation's financial institutions. Five thousand banks failed, setting off a panic that brought business to a standstill. Snell Brothers never recovered and in 1860, the business was taken over by John W. Draper.

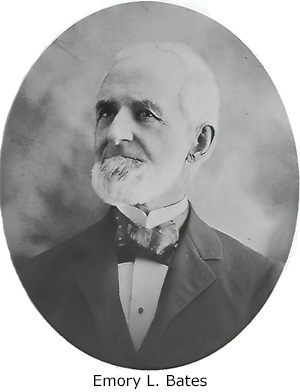

Emory L. Bates assumes leadership

In 1862 Emory L. Bates, a businessman from the nearby village of Fiskdale, partnered with New York hardware firm Clark, Wilson & Company to purchase Snell Brothers from John Draper. The new owners renamed the operation the Snell Manufacturing Company. Bates had been in the shoe manufacturing business for seventeen years, first with the Judson Smith who had been a principal in Smith, Snell & Company, and then from 1850 to 1858 with J. D. Sessions as part of Sessions, Bates & Company.

In 1862 Emory L. Bates, a businessman from the nearby village of Fiskdale, partnered with New York hardware firm Clark, Wilson & Company to purchase Snell Brothers from John Draper. The new owners renamed the operation the Snell Manufacturing Company. Bates had been in the shoe manufacturing business for seventeen years, first with the Judson Smith who had been a principal in Smith, Snell & Company, and then from 1850 to 1858 with J. D. Sessions as part of Sessions, Bates & Company.

When Emory Bates and J. D. Sessions dissolved their footwear company, Bates invested in a third shoe-making enterprise, Bates, King & Company, a manufacturer specializing in cheap russet brogans, most of them destined to shoe the feet of enslaved southerners. His timing could have been better. Southern customers owed the Bates and King operation $87,000 at the outbreak of the Civil War. The hostilities rendered all but $10,000 of the debt uncollectable, and the firm went bankrupt.(11)

Though the failure of the shoe business represented a substantial setback, it did not leave Emory Bates bankrupt. A shrewd businessman, he had other investments, and they were large enough to ensure him a spot on the Board when his new co-partnership became the Snell Manufacturing Company. Bates served as the company treasurer and resident agent from his home in the village of Fiskdale while James Clark Wilson and Hull Clark managed sales and distribution from their firm's Manhattan office.

No longer part of the company's leadership, Thomas, Lucius, and Augustine Snell remained with Snell Manufacturing, retaining considerable responsibility for the production side of the enterprise. Melville Snell, the man responsible for the Snell brothers' migration to Fiskdale area, reported to a Massachusetts census taker in 1865 that he worked as a "forger," presumably with Snell Mfg. A few years later, he moved on to Delaware's picturesquely named South Murderkill Hundred to become a farmer.

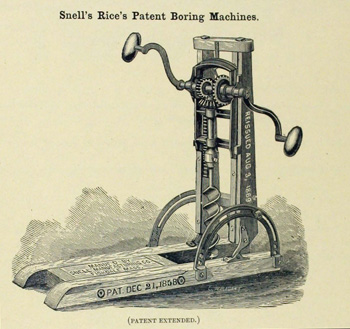

In the 1860s, the Snell Manufacturing Company began selling the wood-frame boring machine patented by George F. Rice, a manufacturer of hay cutters, in 1858. Unlike its predecessors, Rice's machine was adjustable. A pair of bolts projecting from the uprights supporting the boring mechanism engaged a pair of slotted semicircles attached to the base of the machine. Since the uprights were hinged, the carriage could be adjusted to a number of angles and locked into place. The arrangement allowed for boring holes at angles other than the standard ninety degrees and for the frame to be folded flat for shipping.(12)

In the 1860s, the Snell Manufacturing Company began selling the wood-frame boring machine patented by George F. Rice, a manufacturer of hay cutters, in 1858. Unlike its predecessors, Rice's machine was adjustable. A pair of bolts projecting from the uprights supporting the boring mechanism engaged a pair of slotted semicircles attached to the base of the machine. Since the uprights were hinged, the carriage could be adjusted to a number of angles and locked into place. The arrangement allowed for boring holes at angles other than the standard ninety degrees and for the frame to be folded flat for shipping.(12)

Emory Bates acquired the rights to the machine for Snell Manufacturing and had the patent reissued in 1869. Cutting edge at the time, George F. Rice's design began showing its age as the decades passed. By the early 1890s, it had come to be viewed as an inexpensive alternative to the premium adjustable boring machines on the market. The Snell Manufacturing Company also sold a non-adjustable boring machine, similar in appearance, if not functionality, to Rice's 1859 patent.

A perusal of The New England Business Directory for 1865 indicates Snell Mfg. still operated a sawmill. The listing is more specific than earlier mentions, identifying the operation as a shingle mill. A later edition of the directory reveals both Snell and Worcester-based George Rice sold his adjustable boring machine in 1868.(13) The Massachusetts Register for 1869 lists Rice as a manufacturer of hay cutters but makes no mention of him selling boring machines. Since an ad in the 1869 directory refers to Snell as a manufacturer of augers, auger bits, and boring machines, it appears that production of Rice's boring machine moved from Worcester to Fiskdale in 1868.(14)

In 1869, Webb's New England Railway and Manufacturers' Statistical Gazetteer included the following information about the Snell operation on page 360.

They occupy 3 buildings 48 x 140 feet, 3 stories high, main shop 45 x 32 feet, two stories with tower 4 stories attached to main shop; store house 36 x 60 feet, 2 stories, attached to wing of main shop by a walk from the second stories. Employ 68 hands, doing a business of $65,000 per year. The machinery is driven by water power.

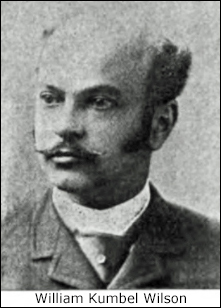

On December 31, 1873, the Snell Manufacturing Company's New York sales agent, Hull Clark, retired from Clark, Wilson & Company. His son, James Clark Wilson, and his grandson, William Kumbel Wilson, joined Henry L. Butler, jr., and Albert Ferguson to form a co-partnership and reorganized the business as J. Clark Wilson & Company. Their enterprise failed four years later. William Kumbel Wilson and investor Frank F. Tennis picked up the pieces and formed a new entity, Tennis & Wilson.(15) Snell Manufacturing, by virtue of Emory Bates' minority stake in the business, traveled along with each reorganization of the New York agency.

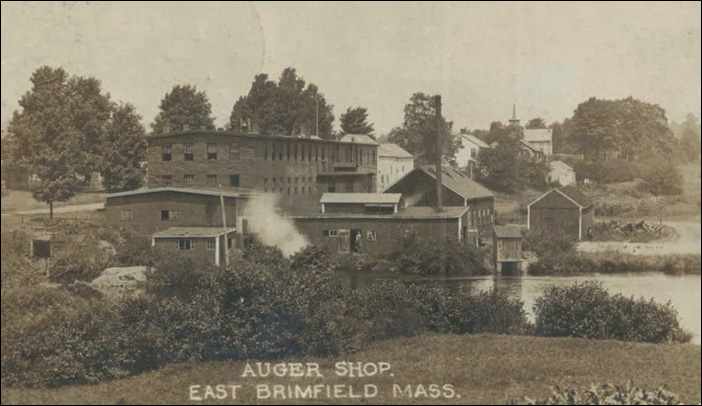

An 1879 ad in the trade periodical Iron Age reveals that Tennis & Wilson served as the sole sales agent for Snell Manufacturing's products and that the line was extensive. Snell manufactured several patterns of carpenters' augers, boring machines and the augers for them, gimlets, car bits, millwright's augers, rafting augers, boat-builders bits, coopers' doweling bits, machine bits, countersinks, and screwdriver bits.(16) The obvious omission in what was an otherwise extensive line of boring tools was an item almost certainly part of the original Thomas Snell's offerings—the common ship auger. Emory Bates remedied the situation in 1883 when Snell Manufacturing purchased a mill in East Brimfield, just three miles from Fiskdale. The mill complex, which had served as a factory for the production of shoemakers' tools, became the site of Snell's ship-auger operation.(17) The new line did quite well.

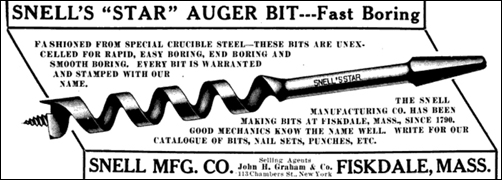

As the 1880s progressed, Emory Bates increased his stake in the New York firm that marketed Snell Manufacturing's products. Tennis & Wilson became Bates, Wilson & Company. When Emory Bates and Kumbel Wilson bought out the other major investors, the firm became Bates & Wilson. The business served as sales agent for a number of manufacturers. In addition to Snell bits, the operation represented such products as Charles Buck edge tools, Leach & Company saw sets, Clark's expansive bits, Peck's shingling hatchets, Morris saw sets, Coe's wrenches, and Reid Lightening Braces.(18) In 1888 Bates & Wilson, abandoned its hardware distribution strategy to focus on manufacturing and began conducting business under the name of its auger and bit production facility, the Snell Manufacturing Company.(19) John H. Graham & Company of 113 Chambers Street in New York City became Snell's sales agent to be joined by Underhill, Church & Co. a few years later.

The Bates Manufacturing Company

The beginning of the 1890s found Emory Bates distributing a line of second-quality Snell-produced auger bits marked with his surname and attributed to the Bates Manufacturing Company. Originally selling for twenty percent less than the Snell brand, they were first made available as double spur bits. Jennings-style bits soon followed. By 1910 the price differential between Bates and Snell products had disappeared.(20) Snell Manufacturing continued to produce the Bates line after his death, through at least 1926.

The stamps used to identify the Bates bits make no mention of the Snell Manufacturing Company. Most are marked with the word BATES with a size number on either the stem or tang. A few are stamped with the term BATES BIT. Some identify the BATES MFG. CO. as the manufacturer. Several examples are seen below.

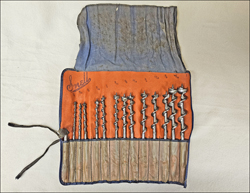

Early Snell containers

As the decades went by, the company replaced its founder's practice of shipping augers by dividing them into lots whose aggregated diameters totaled 100 inches. Paper rolls containing a quarter or half dozen augers of the same eventually size replaced the bulky wooden boxes the earlier method required. In about 1858, the paper rolls were replaced by paper-covered pasteboard boxes constructed by families living nearby.(21) In the 1880s, the idea of providing jobbers with sets of auger bits, containing one each of popular sizes, came into vogue. Popular at the retail level, the hardware industry soon made them available to consumers in cloth rolls and wooden boxes featuring individual slots, clips, or pockets for each bit.

In 1886, Fiskdale resident George E. Richards patented a wooden box for shipping and storing augers bits and assigned the rights to the Snell Manufacturing Company. The company shipped both its Snell and Bates bits Richards' box. In his patent application, he makes an indirect reference to the flaws inherent in the era's most popular retail auger box, the American case. The American Case utilized individual spring-type clips wood-screwed to a transverse bar to hold bits in place. According to Richards, the bits were:

... fastened by metallic spring-clips which engage their shanks, so as to hold them in the box and keep them apart, preventing injurious contact. This mode requires a spring for every bit, and has been found defective by reason of the liability of the springs, to become bent, weak, and ineffective, so that it is not uncommon in opening a box to find the bits mingled in a confused mass, and consequently more or less injured.(22)

As anyone who has ever encountered a set of augers bits in an American Case can attest, Richards' criticism of the box's design was certainly valid. It is ironic then, that when Snell Manufacturing abandoned the use of internally designed boxes in the early twentieth century, it chose to ship its cheaper bits in American Cases. The company shipped both Snell and Bates-branded bits in its Richards boxes.

With its extra pair of hinges and two holding clasps, the Richards Box was expensive to produce. Snell soon developed an economy box that utilized a pair of small wooden slats to hold bits in place. Fitted into slots cut into the interior of the box, the slats ensured that bits residing in grooves in the box's transverse crossbar did not escape. Rotating the slat allowed for its removal, freeing the bits. Elegant in its simplicity, the company's economy box is most frequently seen housing Bates-branded bits.

Snell Mfg. eventually replaced Richards' box with a wire-and-catch design that held bits in place at two points along their length rather than one. The new box addressed the weakness inherent in single point-of-retention boxes: the need to screw the tip of a bit into the top panel of a box the keep the bit in place while the box is being opened, closed or transported. The Snell design employed a rotating catch to lock a stiff interior wire in place, keeping the bits from falling out of a series of slots cut into a transverse crossbar. The wire, inserted into both sides of the box and shaped like a half-rectangle, could be rotated nearly 180 degrees to allow the removal of the bits when the catch was released. They were produced at least through ca. 1910.

The Auger Bit Association and the Fires

By March of 1893, American auger manufacturers were producing so many standard augers and bits that they had become a commodity. A soft economy only compounded the problem. A group of ten auger makers responded by forming the American Auger and Bit Association, an organization whose primary purpose was to set prices for various categories of augers, a practice sometimes referred to as price fixing. The Snell Manufacturing Company Mfg. became a charter member. Notable among the non-participants were the Irwin Auger Bit Company whose unique designs were protected by patent, and the Russell Jennings Mfg. Company whose bits commanded a premium. Snell Manufacturing withdrew from the organization in 1894.(23) The American Auger and Bit Association remained active for some dozen years.

A 2018 survey of the Wright-Snell manufacturing area by the Massachusetts Historical Commission notes:

Between 1870 and 1894, the mill complex consisted of five buildings, including forge shops where augers of various sizes and uses were made and grinding, polishing, and storage rooms ... The buildings were arranged on either side of the canal and tail race dug by Alpheus Wight at the end of the eighteenth century.(24)

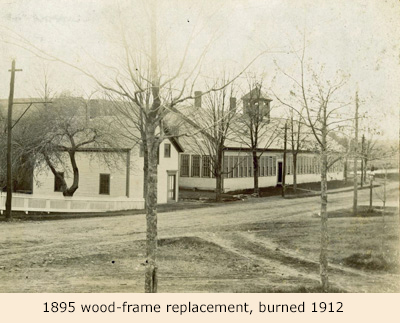

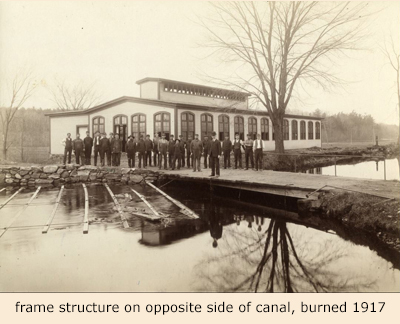

The number of buildings on the site was reduced in 1895 when fire destroyed the company's large three-story factory and the smaller building housing the factory bell tower. Work on a one-story, wood-frame replacement building began immediately. Located on Main Street, the replacement burned to the ground in 1912. The firm replaced the 1895 building with a two-story, wood-frame structure.(25) A second one-story wooden structure, situated on the opposite side of the canal, survived the fire. Built in 1906 to manufacture solid-center auger bits, a fire destroyed it in 1917.(26)

The early twentieth century

Deacon Thomas Snell, no longer with the company due to illness, died in 1885. Augustine Snell passed in 1899 and Lucius Snell, the last of the Snell brothers, in 1906. Emory L. Bates, longtime company president and the man who found the financial backing to reorganize the company during the early years of the Civil War, died in 1900. For all but the last few years of his presidency, Bates was actively involved in managing the Fiskdale and Brimfield operations. As a resident of the area, the arrangement made sense, but as he aged, Bates began to confine himself to financial matters.(27)

Deacon Thomas Snell, no longer with the company due to illness, died in 1885. Augustine Snell passed in 1899 and Lucius Snell, the last of the Snell brothers, in 1906. Emory L. Bates, longtime company president and the man who found the financial backing to reorganize the company during the early years of the Civil War, died in 1900. For all but the last few years of his presidency, Bates was actively involved in managing the Fiskdale and Brimfield operations. As a resident of the area, the arrangement made sense, but as he aged, Bates began to confine himself to financial matters.(27)

Emory Bates left behind a profitable business employing some 125 hands, two-thirds of whom were considered "skilled artisans." In addition to augers, gimlets, and bits, its primary products, Snell manufactured boring machines, expansive and screwdriver bits, ice picks, nail sets, punches, cold chisels, and the like. His major partner, William Kumbel Wilson, succeeded him as company president. Wilson held the position, at least in name, until his death in 1935 at age eighty-seven. There is little evidence that William Kumbel Wilson, a New Yorker, involved himself in the ongoing operations of the company. With the company's ownership located in New York, most day-to-day operational decisions fell to plant superintendent John F. Hebard, a twenty-year veteran employee who oversaw operations at both the Brimfield and East Fiskdale plants.

Some new products

Property and product development did not cease with the change of the Snell Company's leadership. In 1905, Snell introduced its King Auger Bit, a single-twist, double-cutter, extension lip bit similar in appearance to that manufactured by the Ford Auger Bit company. A year later, Snell built a one-story, wooden building for the manufacture of the solid-center Irwin bit whose patent had expired in 1904.(28) The company sold the bit as the "Three Thirty-Three" for several years but soon dropped the moniker in favor of the simple "Snell's Solid Center" designation.

Although Snell's King Auger Bit did not sell well, the company introduced a second single-twist product, the Star Auger Bit, in about 1909. The new bit, a knockoff of the design patented by Henry C. Lewis in 1869, featured a single cutter and one extension lip.(29) It succeeded where the King Auger Bit failed, and the King bit went out of production shortly after the Star was introduced. The company touted the Star bit's ability to bore in knotty or green wood, and in end grain. It excelled in situations where speed was more important than creating a tidy hole and was available as late as 1925.

By the 1920s, Snell had become one of the plethora of auger makers to produce a version of William A. Clark's expansive bit, a wildly popular bit that could be adjusted to cut holes in a variety of sizes whose patent protection had expired. Relatively late to the game, the company may have been put off by the machining that the tool required as its primary expertise lay in forging. Snell would not produce an expansion bit of its own design until the 1940s when it introduced the Snell Simplex.

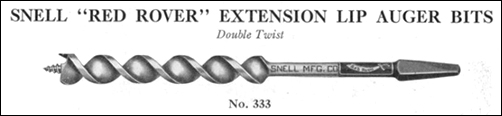

Snell added a copy of the popular Ives Mephisto bit to its lineup in the mid-1920s. A double-twist, single-cutter, single extension-lip auger bit, especially good for drilling through laths, plaster, and the occasional nail, Snell marketed its bit as the "Red Rover." An almost exact copy of the Mephisto, it even featured the red-painted tang that characterized its predecessor.

The company assigned the stock number 333 to its Red Rover bits. Though Snell had used the number for its early solid-center bits, the Red Rover models had nothing to do with the earlier model.

Later retail containers

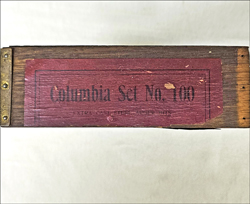

One of the last unique boxes used by Snell Manufacturing was that designed for the short-lived King Auger Bit in 1904. Snell discontinued its custom bit boxes around 1910 and switched to the popular box patented by George H. Bartlett in 1893. Snell referred to its Bartlett boxes as Columbia Boxes through at least the mid-1920s and for a time, referred to bits packed in them as "Columbia Sets." While premium sets were packed in Bartlett boxes, cheaper sets might appear in cardboard boxes, in the American Case, or inexpensive sliding-top boxes. Vinyl rolls succeeded those made of cloth in later years.

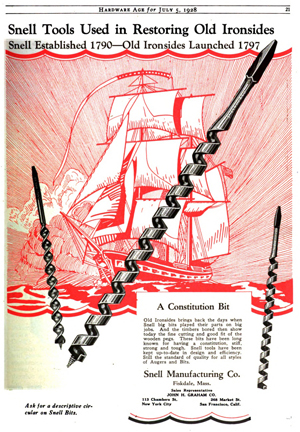

The "Old Ironsides" promotion

The 1928-1931 restoration of the much-beloved battleship known as Old Ironsides—more properly the USS Constitution—gave Snell Manufacturing the opportunity for a public relations bonanza. The ship had deteriorated to the point water had to be pumped out of it daily and by 1925, decay had reached the point where the vessel threatened to break into two pieces. A national committee was formed, and following a much-publicized fundraising campaign in which elementary school children donated their pennies to the cause, lithographs and souvenir pieces from the ship were sold. Approximately two-thirds of the cost of the one-million-dollar restoration was funded by non-governmental entities before a hesitant Congress stepped in to finish the rest.

The 1928-1931 restoration of the much-beloved battleship known as Old Ironsides—more properly the USS Constitution—gave Snell Manufacturing the opportunity for a public relations bonanza. The ship had deteriorated to the point water had to be pumped out of it daily and by 1925, decay had reached the point where the vessel threatened to break into two pieces. A national committee was formed, and following a much-publicized fundraising campaign in which elementary school children donated their pennies to the cause, lithographs and souvenir pieces from the ship were sold. Approximately two-thirds of the cost of the one-million-dollar restoration was funded by non-governmental entities before a hesitant Congress stepped in to finish the rest.

Snell Manufacturing was not about to let a good marketing opportunity go to waste. Thomas Snell, the company's iconic founder, was reported to have set up shop in Ware in 1790 and hauled his completed augers to Boston. Records show that workers at Thomas Hartt's Boston shipyard laid the keel for Old Ironsides in 1794, and after a lengthy delay caused by political wrangling, the vessel was launched in 1797.

The officers of Snell Manufacturing believed that bits manufactured by the company's founder were used in the construction of the iconic frigate and donated the auger bits used in the restoration. The gift, of course, made for good publicity. Though there are no records linking Thomas Snell's augers to the ship, it is possible some of his products were used in its construction. It's also possible that the tens of thousands of holes created during the construction of Old Ironsides were bored by traditional gimlets and pod augers. Then too, there is no way to determine at which points during the senior Thomas Snell's forty-three-year career he hauled his tools overland to Boston.

A careful reading of an ad placed in a 1928 trade periodical by Snell's sales representative, the John H. Graham Company, reveals the New York firm implied a connection between Snell and the famous ship rather than stating it as fact.(30) Nonetheless, those associated with the firm presumed the story to be true until the company's final dissolution in 1954.(31)

Depression, bankruptcy, closure

The Great Depression had its impact on Snell as it did on most of the industrial concerns in the New England area. Early on, the company closed its East Brimfield shop and moved the equipment to its plant in Fiskdale. Later, it reduced its workweek to three days. William Kumbel Wilson, who succeeded Emory Bates as company president, died in February 1935 at age 86. While his presidency was lengthy, it is unlikely he was still at the helm when he passed. A description of the business at the time of his death notes that the company was in "steady condition" owing to "the breadth and diversity of its market." The assessment, appearing in a biographical dictionary of uneven quality, was dated and likely inaccurate, for Snell went bankrupt in 1940. At that point, Dwight E. Priest, the president of Parker Manufacturing Company, purchased Snell Manufacturing and made it a subsidiary of that firm. The restructured Snell retained its original name and focused on the production of expansive (the Snell Simplex) and power tool bits.(32)

When the Millers Falls Company quit the auger bit business in 1945, Snell Manufacturing Company bought the machinery and removed it to Fiskdale. The following year, it moved some of the equipment back to Turners Falls to take advantage of the skills of former Millers Falls auger workers living in the area.(33) Snell's headquarters and main plant remained in Fiskdale until 1952, when Parker Manufacturing sold the real estate, and most of the equipment. Parker moved its wood-boring operation to Worchester.(34) Two years later, Parker Manufacturing closed the Snell operation.

Illustration credits

- Detail of 1830 manuscript map: Plan of Ware, surveyor's name not given, dated 1830. Manuscript map held by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Archives.

- Snell & Bros. auger stamp: author photo.

- Emory L. Bates portrait: Burns, Brian. Sturbridge: a Pictorial History. Norfolk, Virginia : The Donning Company, 1988. p. 32.

- Rice boring machine: [Catalog]. New York : John H. Graham & Company, 1891 p. 57.

- Drawing of Snell factory (from map): O.H. Bailey & Co. Sturbridge and Fiskdale. Massachusetts. Boston: O.H. Bailey & Co., 1892.

- East Brimfield Auger shop. Postcard. Publisher and date of publication unknown. Postmarked 1907.

- Bates Bit stamps: author photos.

- Richards, slot-and-keeper, and wire-and-catch boxes: author photos.

- Snell wooden buildings: Digital Commonwealth: Massachusetts Collections Online. https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:fb494r55m (viewed March 23, 2024); https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:fb494r575 (viewed March 23, 2024)

- William Kumbel Wilson: Howard, Henry W. B., ed. The Eagle and Brooklyn: the Record of the Progress of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle ... Brooklyn : The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 1893. p.856-857.

- King Auger Bit Box: Catalogue of Hardware. New York: Underhill, Clinch & Company, ca. 1910. p. 142.

- Bartlett & Columbia-branded boxes: author photos.

- Vinyl roll: author photo.

- Star auger bit: The Hardware Reporter. October 25, 1912. p. 33

- Red Rover bit: Snell Augers, Bits and Small Tools: Catalogue No. 34. Fiskdale, Massachusetts: Snell Manufacturing Company, 1924?

- Old Ironsides promotion: "Snell Tools Used in Restoring Old Ironsides." Hardware Age. July 5, 1928 p. 21.

- Snell Simplex bit: author photo.

References

- "The American Screw Auger." The Chronicle of the Early American Industries Association. Vol. 64, no. 3 (September 2011), p. 89-107.

- Chase, Arthur. History of Ware, Massachusetts. Cambridge, Mass. : The University Press, 1911. p. 8, p. 225-227.

- Hebard, John F. "Snellville and its Manufactures." Quinabaug Historical Society Leaflets, v. 2, no. 4, 1907. p. 32.

- "New and Fashionable Goods" Greenfield Gazette and Franklin Herald (Greenfield, Mass.). January 22, 1828. p. 3.

- Plan of Ware, surveyor's name not given, dated 1830. Manuscript map held by the Massachusetts Archives.

- Barber, John Warner. Historical Collections: being a General Collection of Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes ... Worcester Mass. : Dorr, Howland & Company, 1839. p. 344.

- Hurd, D. Hamilton. History of Worcester County Massachusetts: with Biographical Sketches of Many of its Prominent Men. Vol 1. Philadelphia: J. W. Lewis & Co., 1889. p. 119.

- Morse, A. C. "Sturbridge.” in History of Worcester County, Massachusetts: Embracing a Comprehensive History the County from its First Settlement to the Present Time. Vol 2. Boston : C. F. Jewett & and Company, 1879. p. 370-371.

- The Massachusetts Register: a State Record for the Year 1852. George Adams: Boston, Massachusetts, 1852, p. 224.

- Burns, Brian. Sturbridge: a Pictorial History. Norfolk, Virginia : The Donning Company, 1988. p. 32.

- Biographical Review: Containing Life Sketches of Leading Citizens of Worcester County Massachusetts, Vol. 30. Boston: Biographical Review Publishing Company, 1899. p. 636.

- United States Letters Patent No. 22,379.

- The New England Business Directory. Boston : Sampson, Davenport & Company, 1865. p. 462; The New England Business Directory. Boston : Sampson, Davenport & Company, 1869. p. 395.

- Massachusetts Register, 1869: Containing a Record of State and County Officers, and a Directory of Merchants, Manufacturers, etc. Boston : Sampson, Davenport & Company, 1869. p. 763.

- "Bates & Wilson." Illustrated New York: Metropolis of Today. New York : International Publishing Company, 1888. p. 137.

- [Advertisement]. The Iron Age. (April 3, 1879). p. 8.

- "East Brimfield ... the Lost Village." Brimfield Pocket Guide: Dealer Directory and Map. Brimfield Mass. : Brimfield Exchange, July 2003. p. 4.

- Illustrated New York, p.137.

- Howard, Henry W. B., ed. The Eagle and Brooklyn: the Record of the Progress of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle ... Brooklyn : The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 1893. p. 856-857.

- Catalogue of Hardware. New York: Underhill, Clinch & Company, ca. 1910. p. 143. (part of the Smithsonian Trade Catalog Collection)

- Hebard, p. 32.

- United States Letters Patent No. 350,016.

- "Augers and Bits." The Iron Age. (March 16, 1893). p. 635; "Augers and Bits." The Iron Age. (May 17, 1894). p. 959.

- Massachusetts Historical Commission. Inventory Form A: Sturbridge, Wright-Snell Manufacturing Area. Boston : the Commission, 2018. sheet 6. https://www.sturbridge.gov/sites/g/files/vyhlif12111/f/uploads/wightsnellmfgarea.pdf (viewed 03/13/2024)

- Burns, p. 32, 34-35.

- "$20,000 Sturbridge Fire." Boston Globe (Boston, Mass.) February 9, 1917. p. 9.

- Biographical Review, p. 639.

- Hebard, p. 33.

- United States Letters Patent No. 90,759.

- "Snell Tools Used in Restoring Old Ironsides." Hardware Age. July 5, 1928 p. 21.

- "Firm that Made Tools for Constitution Closes." North Adams Transcript (North Adams, Mass.) July 1, 1954. p. 1.

- The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. New Series. Vol. 32. New York; James T. White & Company, 1936. p. 63.

- "New Industries Begin Operations in Turner's Falls." Greenfield Recorder-Gazette, (Greenfield, Mass.) June 29, 1946. p. 5

- "Liquidation by Public Auction." The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts). July 27, 1952. p. A7.