Job T. Pugh

The Job T. Pugh Company claimed to be the oldest manufacturer of auger bits in the world, a factual statement if you consider a succession of six family-related businesses to have been a single enterprise. The Pughs, an old Philadelphia family, took pride in a line of descent that extended back to the Colonial Period and in an auger-making business whose history included no less than three Job T. Pughs.

The Job T. Pugh Company claimed to be the oldest manufacturer of auger bits in the world, a factual statement if you consider a succession of six family-related businesses to have been a single enterprise. The Pughs, an old Philadelphia family, took pride in a line of descent that extended back to the Colonial Period and in an auger-making business whose history included no less than three Job T. Pughs.

Tradition and legend

It's hard to determine how much of the Pugh Company's representation of its early history was based on a misunderstanding of its role in the development of the American auger bit and how much was marketing hyperbole. Early records are scarce. The predecessor to the United States Patent Office, the Patent Board, did not come into existence until 1790, and unless the company kept a meticulous archive, there were few sources available to verify information passed on by word of mouth. There is no record to indicate that either partner in the founding Brooke & Pugh enterprise attempted to patent the double-twist auger later generations claimed to have been invented by Job T. Pugh, 1st, in 1790.

It has been fairly well established that William Henry and John Henry Rauch of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, put a double-twist auger on the market 1772—eighteen years before Brooke & Pugh.(1) Though the invention of what became known as the "Pennsylvania screw auger" did not lay with the business founded by Benjamin Brooke and Job T. Pugh in 1774, their enterprise was without a doubt one of the earliest and most prolific manufacturers of the product. Though Pugh's descendants credited him with developing the company's premiere product, his father-in-law and business partner Benjamin Brooke may have had just as much to do with it. In 1891, a random tidbit, long on lore and short on facts, appeared in the journal American Notes and Queries. It was reprinted in a handful of U. S. newspapers:

The auger with the twisted shank, which makes it self-discharging, is also the result of an accidental discovery. The screw auger is an American invention dating back to the year 1774, when John White and Benjamin Brooke of Hammer Hollow, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, noticed some boys boring holes in the ground with some pieces of hoop iron. One of these, which had been twisted, was seen to bring up the dirt each time as it made a complete revolution. Being men of an observing turn of mind, White and Brooke began to debate the possibility of constructing a tool for boring wood on the same principle. It was immediately tried, with the addition of a screw point for drawing the cutting edge into the wood. It is needless to add that the experiment was eminently successful.(2)

The tale had appeared a decade earlier in The Peoples' Condensed Library: a Compendium of Universal Knowledge, a volume that also mentions that Job T. Pugh, 1st, once worked as Brooke's apprentice.(3)

The Job T. Pugh Company made much of the role its bits played in boring the holes in the lumber used to construct the "oaken yoke" of the Liberty Bell. On the surface, the story is plausible. The firm had been in existence since 1774 and its bits were a staple in the kits of many a Philadelphia workman. A closer examination of the facts makes the assertion hard to verify. The National Park Service believes the elm-wood cradle supporting the bell is the original. If this is true, Pugh bits could not possibly have been used because the bell dates back to the early 1750s. Given the distance in time and that the bell was re-hung several times, it is unlikely the Pugh claim will ever be verified.

The early Pugh firms

Between 1774 and 1872, the Pugh family businesses underwent at least four name changes:

- Brooke & Pugh (1774-1818) Benjamin Brooke and Job T. Pugh, 1st

- Benjamin Pugh (1818-1857) sole proprietor

- Benjamin Pugh & Co. (1857-1863?) Benjamin Brooke Pugh, Charles Fye Pugh, Job T. Pugh, 2nd

- Pugh & Brother (1864?-1872) Job T. Pugh, 2nd, James H. Pugh.

The partnership of Benjamin Brooke and his son-in-law Job T. Pugh, 1st, made small tools, including "flat augers" which sound like nothing so much as garden-variety center bits. In 1790, the partners began to manufacture the double-twist augers that would become the Pugh Companies' primary source of income until the dissolution of the final incarnation of the business in 1954. Job T. Pugh, 1st, passed away in 1802 when his son Benjamin Pugh was five years old. Chronologies later distributed by the company give the impression that the business retained its original Brooke & Pugh name until the younger Pugh assumed control in 1818 at the age of twenty-one. Early square-shafted augers stamped "J. PUGH" are known. While almost certainly pre-dating 1860, it is unlikely they date back to the time of the first Job T. Pugh.

Considering that he spent thirty-nine years as an auger maker, Benjamin Pugh, left little evidence of his activities. His augers turn up infrequently. He seldom advertised. The picture that emerges is that of a small shop conducting a steady, mostly local business. Three Benjamin Pugh stamps have been recorded:

B. PUGH

BENJ. PUGH

B. PUGH

PHILADA

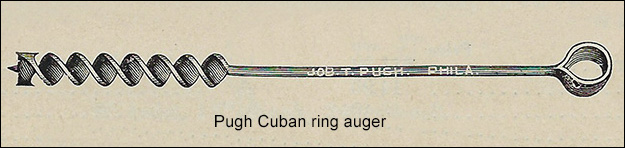

Benjamin Pugh's older sons: Job. T. Pugh, 2nd, Benjamin Brooke Pugh, and Charles Fry Pugh took over their father's business after his death and renamed it Benjamin Pugh & Company.(4) The following year they introduced an auger designed for use on tropical hardwoods that came to be known as Pugh's Cuban Ring Auger. There was little new in the product. Ring-type T-augers had long been in existence. The Pughs simply added a coarse, single-thread lead screw to a double-twist ring auger. Their contribution to the development of the tool lay not so much in design but in the product itself. Boring large-diameter holes in tropical woods is tough going. Considering the stress on the tool, the quality of the steel in the augers must have been first-rate. The Cuban Ring sold well for decades, especially in the Caribbean area. The company's description of its ring augers in its 1921 catalog includes the following:

The "Pugh" Ring or Cuban Augers are absolutely the only augers that will successfully bore lignum-vitae and other woods of tropical countries. The first augers to give perfect satisfaction in boring these woods were introduced into Cuba in 1858 by Job T. Pugh, having just at that time invented the "Pugh" single threaded screw, which is the only screw that will not clog in these hard woods. We annually ship thousands of the augers to Cuba and the other West Indian Islands, as well as to Central and South America and adjoining countries. While the railroads and car shops use them in greatest abundance, the are also used in the other varied industries of these countries.(5)

Though the date for the dissolution of Benjamin Pugh & Company remains unknown, it likely came about as the result of Benjamin Brooke Pugh's demise in 1863.

A company chronology developed by Job. T. Pugh, 2nd, in 1876, simplified the complex and fluid situation that existed between the death of the original Benjamin Pugh in 1857 and that of his youngest son James in 1872. The chronology ignores the existence of Benjamin Pugh & Company, the business that existed from 1857 to ca. 1863 and simply lists the company's 1857-1872 name as Pugh & Brother.(7) During this period, Benjamin Brooke Pugh died of an effusion on the brain at age thirty-one; Charles Fry Pugh died at age thirty-four of tuberculosis; and the youngest brother, James Hananiah Pugh, died of heart disease at thirty-three. Since the chronology was developed as part of an advertisement for the firm, its brevity was a virtue. As a record of the myriad changes the company went through, however, it leaves much to be desired.(6)

Job T. Pugh, 2nd

With the death of his brother James in 1872, Job. T. Pugh, 2nd, became the sole proprietor of the operation. Though much of what happened on the production side of the family business remains opaque, J. T. Pugh, 2nd, was largely responsible for creating the image of a historic American enterprise with roots going back to pre-revolutionary times. The impetus for his look backward may have been Philadelphia's sponsorship of the 1876 Centennial Exposition, an event celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. The exposition, the first official World's Fair held in the United States, was years in the planning, and a big part of its mission was to present an overview of developments in science, manufacturing, and transportation.

Pugh took advantage of his operation's status as a century-old establishment, getting his company's name included in the ubiquitous lists of the nation's oldest businesses popping up in the press at that time. In a break with the family's parsimonious traditions, he went so far as to buy a small advertisement in a locally published centennial guide where he proudly referred to himself as the "Sole Proprietor of the Old Auger Establishment."(7) The Job T. Pugh operation mounted a display of its augers in the Exposition's hardware department, a smart move since the fair drew ten million visitors during its six-month lifespan. Interestingly, there is no evidence the company referred to its auger bits boring holes in the yoke of the Liberty Bell at this time. The claim appeared much later.

When Job T. Pugh, 2nd, died of a stroke in 1885 at age fifty-five, the business passed on to his children—the great-grandchildren of the first Job T. Pugh. The new owners were Job T. Pugh, 3rd; Charles R. Pugh; and A. M. Pugh. The partners left the name of the business unchanged, and Job T. Pugh, 3rd, managed the operation. Little is known about the roles played by Charles R. or A. M. Pugh. Charles R. Pugh died of a pulmonary hemorrhage at age thirty-one, just two years after becoming a principal in the business. It is a sign of the times that the company took care to avoid the use of A. M. Pugh's given name—Anna Mary.

When Job T. Pugh, 2nd, died of a stroke in 1885 at age fifty-five, the business passed on to his children—the great-grandchildren of the first Job T. Pugh. The new owners were Job T. Pugh, 3rd; Charles R. Pugh; and A. M. Pugh. The partners left the name of the business unchanged, and Job T. Pugh, 3rd, managed the operation. Little is known about the roles played by Charles R. or A. M. Pugh. Charles R. Pugh died of a pulmonary hemorrhage at age thirty-one, just two years after becoming a principal in the business. It is a sign of the times that the company took care to avoid the use of A. M. Pugh's given name—Anna Mary.

Job T. Pugh, 3rd

Planning for the company's participation in the 1887 Centennial Celebration of the United States Constitution began shortly after Job T. Pugh, 3rd, took office. Compared to the massive Centennial Exposition of 1876, Philadelphia's 1887 celebration of the 100th Anniversary of the U. S. Constitution was a modest affair. A three-day commemoration, it was for the most part, a local celebration. The Job T. Pugh company sponsored a parade float for an event called the Civic and Industrial Procession. A description of the mobile exhibit is interesting in that it gives a good idea of the extent of the company's product line. The display featured hundreds of items, including machine bits, car bits, carp augers, mill augers, post augers, pump augers, and ring augers, as well as hollow chisels, dowel bits, countersinks, and gas augers for boring through brick. The writer describing the float seemed especially impressed by the largest auger the firm had ever made. "Its diameter was seven and one-half inches, and it will bore any kind of wood, with power or by hand. It was of uniform shape, etc., and thirty inches long."(8)

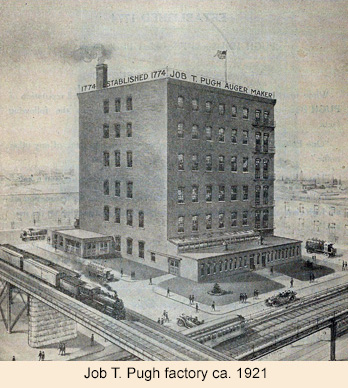

Job T. Pugh, 3rd, was a good manager, and under his direction, sales increased to the point that a new facility became necessary. In 1894, the company completed work on a new seventy-by-seventy-foot brick building with four stories and a basement. Pugh ordered a fair amount of new machinery, had the heaviest installed in the basement, and put the rest on the first floor. The offices and stock rooms took up the remainder of the building. Though electricity was coming into vogue, gaslights provided the business' illumination. An elevator stopped on all floors.(9)

As the 1890s progressed, the Pugh Company began paying more attention to the benefits of getting its name into the trade literature. The business had never polished the inside spirals of its double-twist augers and now began to brand them as "Black Twist." In doing so, it hearkened back to its early days:

In those olden times, the feature of any manufacturer was the excellence he could produce in quality, and, as nearly everything was made by hand, it did not receive the beautiful polish that, at the present day, adorns the cheaper and inferior implements. In preference to a polished surface, the discoverer and manufacturer of the Double-Twist Augers made the twist black and unpolished. It thus showed the hand-work that had been put upon it, and it is still a well-known fact that handmade tools are far superior in quality and workmanship to all others. As manufacturing industries increased, augers began to be made with high polish and beauty, but the consumer spoon found they were of inferior quality, and inquire for the Black Twist Auger, knowing it to be the old-fashioned genuine kind; and today it is called for when the name Pugh has been lost. Thus, the Pugh auger acquired for itself the name "Black Twist," and it has always been retained as a Trade Mark. ... Other manufacturers, knowing the reputation of the Black Twist Augers, have made imitations of them and are still doing so.(10)

Auger bits with unpolished twists were long the norm. Companies other than Pugh were slow to adopt the polished style, so they could hardly be called imitators. On the other hand, the claim that Pugh bits were "handmade" had some basis in fact. Photos of the forging operation and twisting process taken in the early years of the 20th century depict an operation proudly wedded to tradition.(11)

Auger bits with unpolished twists were long the norm. Companies other than Pugh were slow to adopt the polished style, so they could hardly be called imitators. On the other hand, the claim that Pugh bits were "handmade" had some basis in fact. Photos of the forging operation and twisting process taken in the early years of the 20th century depict an operation proudly wedded to tradition.(11)

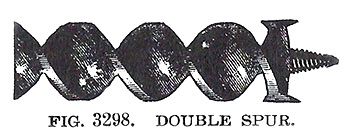

Though the Pugh operation made a variety of bits including Russell Jennings style and scotch lip augers, most of its carpenters' bits featured double-spur cutting heads. Though the double-spur pattern is an old one, there is no evidence that anyone affiliated with the Pugh companies came up with the idea, nor did they lay claim to it. The design features a pair of spurs that extend above and below the floors of a pair of cutting lips. One advantage of the double-spur bit is the built-in redundancy of its spurs. If either of the leading spurs is broken off, the remaining backward-pointing spur retains its ability to score the edges of the hole. Under the direction of Job T. Pugh, 3rd, the company used high-grade English steel for its handmade augers. Its double-spur bits were among the best-of-type on the market and among the most expensive.(12)

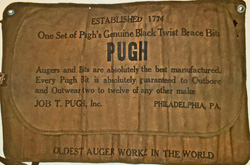

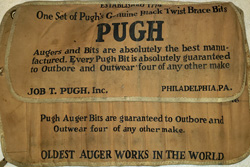

The Job T. Pugh Company stamped its name on the tangs of its bits, rather than the shanks. Never let it be said that the company chased after the latest fad; the practice was common among bit makers through the 1880s. In the early years of the 20th century, the firm began gluing a paper label to the shanks of its most popular augers as well. Most that have survived have become unreadable. Printed with gold letters on a black back, the stickers proudly announced:

ESTABLISHED 1774

HANDMADE

JOB T. PUGH, Phila.

Beware of Imitations

WARRANTED

Like its competitors, Pugh offered its customers the option of purchasing sets of carpenters' bits in wooden boxes and canvas rolls. The finger-joint boxes were fitted with a coil spring retainer that held the bits in place. Other businesses, such as the Ford Auger Bit Company and C. E. Jennings used the coil-spring option as well but chose to fit the spring at a ninety-degree angle to the long sides of the box, making the bits less likely to get out of order.

The J. T. Pugh Company's canvas bit rolls make for an interesting study in advertising excess. The firm was one of several auger bit manufacturers to place large-text ads on canvas rolls they supplied with their bits. The Job T. Pugh ads were surely the most outrageous—though in the company's defense, it did tone down its claims as the years progressed. Its early twentieth-century rolls informed the user that a single Pugh bit would "Out Bore and Out Wear from 12 to 25 of any Other Make."

Either the company's over-the-top advertising was wearing thin, or the quality of its competitors' bits improved dramatically, for shortly after 1917, the auger bit rolls promised: "Every Pugh Bit is guaranteed to Outbore and Outwear two to twelve of any Other Make." By the late 1920s, the company modestly guaranteed that one Pugh Bit would "Outbore and Outwear four of any Other Make."

The twentieth century

Unlike his predecessors, Job. T. Pugh, 3rd, was willing to spend moderate sums to get ads in the hardware and construction trade literature. His ads were small, but frequent, and must have been successful. Business boomed, and in 1900, the company found it necessary to add another two floors to its seven-year-old factory and upgrade its boiler and electric plant. The construction was barely complete when a fire burned out the building's fourth floor and equipment and supplies on the lower levels were water-damaged.(13)

Unlike his predecessors, Job. T. Pugh, 3rd, was willing to spend moderate sums to get ads in the hardware and construction trade literature. His ads were small, but frequent, and must have been successful. Business boomed, and in 1900, the company found it necessary to add another two floors to its seven-year-old factory and upgrade its boiler and electric plant. The construction was barely complete when a fire burned out the building's fourth floor and equipment and supplies on the lower levels were water-damaged.(13)

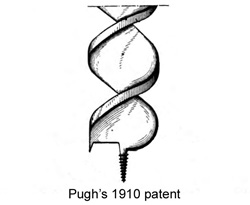

In 1910, the United States Patent Office awarded the Job T. Pugh company the only recorded patent in the firm's 180-year history. Pugh had designed a double-twist auger bit with a single spur and a floor gouge lip. The inventor maintained his bit's gouge-type lip and single spur avoided the chiseling action of traditional double-cutter bits that he believed led to the chipping and splitting of delicate woods. There is no evidence that the Pugh organization brought the bit to market.(14)

References to the use of Pugh augers to bore holes in the yoke of the Liberty Bell appear to date from a company profile published in 1916. Job T. Pugh, 3rd, had enrolled his business in The Association of Centenary Firms and Corporations of the United States. When the association put out a call for brief histories of its member organizations, his two-page summary became a part of a volume celebrating the long-lived enterprises and their achievements.(15) Job T. Pugh, 3rd, included the Liberty Bell detail in his company's profile. Though it is highly unlikely the business was involved in the original construction of the bell's wooden support, the story may not have been entirely false. When the Liberty Bell was removed from the tower of Independence Hall in 1894 and put on display in the East Room, the Philadelphia Enquirer noted:

The rough hewn oaken yoke from which the bell first hung was ready to bear its weight once more, being mounted on handsome bronze supports on a square platform of polished white oak. When the bell was gotten into position it was found necessary to cut two depressions in the old oaken yoke, in which to sink the iron nuts holding the bolts in place. The chips were eagerly seized by carpenters, reporters and a few others who watched the work.(16)

It is possible that Pugh bits were used to bore the countersinks when the bell was mounted for display, and if they were used in 1894, rather than earlier, why trouble with details that would detract from the assumption that the company played a minor role in the struggle for American independence?

On August 31, 1917, the Pugh family incorporated its company in Delaware as Job. T. Pugh, Inc. Three months later, Job T. Pugh, 3rd, passed away, and his widow, Lucy W., became the new corporation's president. Lucy Pugh held the company presidency for thirty-seven years—through changes in technology, the Great Depression, and World War II—until the sale of the factory and the firm's dissolution in 1954.(17) Lucy Woodward Pugh passed away in 1956 at age eighty-nine.

The Philadelphia Bit Company - The Philadelphia Bit Works

At some point in the early 20th century, the Job T. Pugh Company manufactured a second line of auger bits under the name Philadelphia Bit Company. The reason for the decision to do so is unknown. The bits may date from the time the last of the Job T. Pughs passed away and reflect a temporary confusion about what to call the company or they may have been a second line introduced to broaden the manufacturer's share of the market. The business did an odd job of branding the bits. Wooden boxes containing the new auger bits featured interior labels noting that the Philadelphia Bit Company was established in 1774—the year the Job T. Pugh company claimed as its founding date. Additionally, the labels listed the location of the Philadelphia Bit Company's factory as West Philadelphia, a neighborhood rather than a true address. The company boxed the bits in cases featuring the coil spring retainer found on sets of its Pugh-branded bits. Though casual retail customers would have been unlikely to connect the bits to Job T. Pugh, those who already owned a set of Pugh bits or worked in the hardware trade were likely to make the connection.

As is the case with its other augers, Job T. Pugh stamped its new line of bits on the tang and did not polish the insides of the twist. The tang stamps read PHIL'A BIT WORKS rather than the Phil'a Bit Company listed on the label. The general appearance of surviving boxed sets suggests a 1900 to mid-1920s date of manufacture.

Illustration credits

- Job T. Pugh factory: Pugh: Catalogue P. Philadelphia : Job T Pugh, Inc., 1921.

- Pugh double-twist bit: author's photo.

- Cuban Ring auger: Pugh: Catalogue P. Philadelphia : Job T. Pugh, Inc., 1921.

- Job T. Pugh III portrait: Morgan, George. The City of Firsts: Being a Complete History of the City of Philadelphia from its Founding in 1682 to the Present Time. Philadelphia : Historical Publication Society in Philadelphia, 1926.

- Double-spur auger: Woodworkers' Tools, Supplies, Machinery, and Similar Goods ... Detroit, Michigan : Charles A. Strelinger & Co., 1897.

- Pugh bit boxes: author photos.

- Canvas roll advertising: author photos.

- 1910 bit design: United States Patent No. 967,055.

- Philadelphia Bit Company images: author photos.

References

- Hutchins, Joseph. "The American Screw Auger." The Chronicle of the Early American Industries Association. Vol. 64, no. 3 (September 2011), p. 89-107.

- "Discoveries by Accident." American Notes and Queries: a Medium of Intercommunication... Vol. 7, no. 15 (August 8, 1891), p. 175.

- "Auger." The Peoples' Condensed Library: a Compendium of Universal Knowledge ... Last ed. Chicago : R. M. Washburn, 1881. p. 277-278.

- Boyd's Philadelphia City Business Directory to which is added ... 1860-61. Philadelphia : William H. Boyd, 1860. pp. 52 & 450.

- Pugh: Catalogue P. Philadelphia : Job T. Pugh, Inc. 1921. p. 13.

- Kidder, Charles Hollander, ed. Burley's United States Centennial Gazetteer and Guide. Philadelphia: S. W. Burley, 1876. p. 749.

- Once again: Kidder, Charles Hollander, p. 749.

- Carson, Hampton L., ed. History of the Celebration of the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Promulgation of the Constitution of the United States. vol 2. Philadelphia : J. B. Lippincott Co., 1889. p. 75-76.

- "Job T. Pugh." The Iron Age. February 1, 1894. p. 235.

- "The Black Twist Auger," The Times (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), Dec. 11, 1898. p. 18.

- "Auger making in an Old American Shop." American Machinist. (February 20, 1908), p. 281-284.

- Wood Workers' Tools: Being a Catalogue of Tools, Supplies, Machinery and Similar Goods Used by Carpenters, Builders, Cabinet Makers, Pattern Makers ... Detroit, Michigan : Charles A. Strelinger & Co., 1897. p. 691.

- “Machinery,” The Age of Steel. September 29, 1900. p.30; "Recent Fires." Hardware. (June 10, 1901). p. 74.

- United States Patent No. 967,055.

- Association of Centenary Firms and Corporations of the United States. Association of Centenary Firms and Corporations of the United States. Second issue. Philadelphia: Christopher Cower Company, 1916. p. 59-60.

- "The Old Liberty Bell: Taken from its Old Place, Never to be Raised Again." The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), June 14, 1894, p. 1.

- "Mrs. J. T. Pugh, 3d." The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). Mar. 20, 1956. p. 8.