Ezra L'Hommedieu

L'Hommedieu in Essex

Most discussions of the American bitstock auger begin with Ezra L’Hommedieu, a ship carver from Saybrook, Connecticut, who patented a double-twist auger in 1809. Patenting an item is not the same as inventing it, and evidence abounds that similar double-twist augers fitted with lead screws appeared earlier in Pennsylvania and other Connecticut locations.(1) Though the romantic image of a humble craftsman toiling in obscurity until he one day discovers a better way of accomplishing a task has its appeal, L’Hommedieu came from a solidly middle-class background and was an established businessman before developing and capitalizing on his patent.

Most discussions of the American bitstock auger begin with Ezra L’Hommedieu, a ship carver from Saybrook, Connecticut, who patented a double-twist auger in 1809. Patenting an item is not the same as inventing it, and evidence abounds that similar double-twist augers fitted with lead screws appeared earlier in Pennsylvania and other Connecticut locations.(1) Though the romantic image of a humble craftsman toiling in obscurity until he one day discovers a better way of accomplishing a task has its appeal, L’Hommedieu came from a solidly middle-class background and was an established businessman before developing and capitalizing on his patent.

Ezra’s father Grover, a patriot minuteman, left Long Island in 1776 when his revolutionary sympathies rendered his situation in British-occupied Long Island untenable. A ropemaker by trade, he booked his family passage across Long Island Sound on a ship captained by Ichabod Cole and fled to Norwich, Connecticut where he lived for a time. Grover L’Hommedieu was already prosperous by the time he relocated to Essex where in 1797 he built the town’s first ropewalk, a facility for making rope, on land he leased from Samuel Lay. The following year he built a beautiful home on the main street in Essex where his son Ezra lived until 1815.(2)

Growing up in the maritime economy of southern Connecticut, Grover’s son Ezra had ample opportunity to participate in the lucrative trades involved in the construction and fitting out of wooden merchant ships. He became a ship carver and while the term conjures up images of the fanciful figureheads that graced the prows of ships in the Age of Sail, much of the work was more mundane and included name boards, stern boards, ornate wooden trim, furniture, and the like. On January 20, 1800, Ezra L’Hommedieu placed a notice on the first page of the Connecticut Courant informing the public that he carried on “the Carving business in all its various branches in Pettipauge Point, Say-Book.”(3) The shop, located near the wharf on the village's main street, no longer exists, but an 1884 history reveals he leased the structure from Samuel Lay, the man who leased Grover L'Hommedieu the property for his ropewalk.(4)

While not involved in the basics of shipbuilding, L’Hommedieu was certainly familiar with the tens of thousands of holes bored to accommodate the wooden trenails and bolts used in constructing a large ship, and he understood the commercial potential of a tool that simplified the job. When L’Hommedieu’s interest in ship carving waned, his enthusiasm for making the augers to bore those holes grew. Just how much he added to pre-existing designs is unknown, but he applied for an auger patent in 1809 and was successful in obtaining it.

The double-podded auger

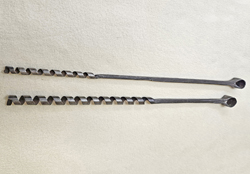

L'Hommedieu referred to his 1809 invention as a “double-podded screw auger.” So few of the earliest double-twist augers have come down to us that it is difficult to see what advantages it may have had over similar designs. In his patent application, L’Hommedieu claimed, “The great superiority of this auger over every other in use consists in its being more strong and durable, in turning much easier, being faster and drawing out of the hole with more ease.”(5) Another advantage may have been the quality of the wire stock used to fabricate his screw augers, which L’Hommedieu sometimes referred to as screws. In November 1809, L’Hommedieu reported to the Secretary of the Treasury that “he made his own wire from which a man and two boys could make per day three hundredweight of assorted screws superior to the imported ...”(6)

L'Hommedieu referred to his 1809 invention as a “double-podded screw auger.” So few of the earliest double-twist augers have come down to us that it is difficult to see what advantages it may have had over similar designs. In his patent application, L’Hommedieu claimed, “The great superiority of this auger over every other in use consists in its being more strong and durable, in turning much easier, being faster and drawing out of the hole with more ease.”(5) Another advantage may have been the quality of the wire stock used to fabricate his screw augers, which L’Hommedieu sometimes referred to as screws. In November 1809, L’Hommedieu reported to the Secretary of the Treasury that “he made his own wire from which a man and two boys could make per day three hundredweight of assorted screws superior to the imported ...”(6)

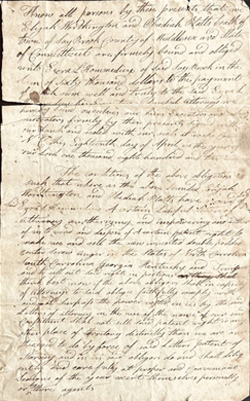

A recently acquired manuscript reveals the extent to which L’Hommedieu and his associates expected a windfall from sales of his double-podded auger. Dated April 18, 1810, the document is a bond, a form of contract common in 18th and early 19th century America. In it, Elijah Worthington and Obadiah Platts, witnesses to L’Hommedieu’s 1809 patent application, agree to pay the inventor the sum of $60,000 for the right to control the manufacture and sale of L’Hommedieu’s double-podded auger in the states of North and South Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, and Tennessee for fourteen years, the life of the patent.

A cash sale it was not. Worthington and Platts agreed to retire the debt by making annual payments from the profits of their enterprise. Their territory consisted of just five of the nation’s seventeen states, two of which were landlocked and the remainder less than hotbeds of ship construction. Depending on the table used to make the conversion, Worthington and Platts indebted themselves and their heirs to the tune of 1.2 to 1.5 million contemporary dollars. By this standard, the value of the patent rights in the twelve remaining states, many on the coast and densely populated, would have been impressive indeed.

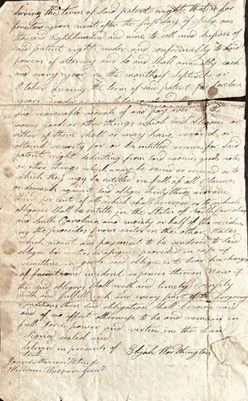

Text of the 1810 bond

The document was written on both sides of a single sheet of paper and bears the remnants of a red wax seal. The sentences are extremely long, and the spelling, punctuation, and capitalization, while erratic, are typical of the times. The transcription provided here retains irregularities but includes commas, periods, and one capital letter added to improve readability.

The document was written on both sides of a single sheet of paper and bears the remnants of a red wax seal. The sentences are extremely long, and the spelling, punctuation, and capitalization, while erratic, are typical of the times. The transcription provided here retains irregularities but includes commas, periods, and one capital letter added to improve readability.

"Know all persons by these presents that we Elijah Worthington and Obadiah Platts boath (both) of Town of Say Brook, County of Middlesex and State of Connectticut, are firmely bound and obliged unto Ezra L’Hommedieu of said Say Brook in the Sum of Sixty thousand dollars. To the payment of which sum well and truly to the said Ezra L’Hommedieu, his Executors, or lawful Attorneys we hereby bond ourselves, our heirs, Executors, and Administrators firmly by these presents, signed with our hands and sealed with our seals, at Wake County NC this Eighteenth day of April in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and ten.

The conditions of the above obligation such that where as the above bounded Elijah Worthington and Obediah Platts have received of said Ezra L Hommedieu A certain Lawful letters of attorney authorizing and impowering and Either of Us to vend and dispose of a Certain patent right to make, use, and sell the new invented double podded Center Screw Auger in the States of North Carrolina, South Carrolina, Georgia, Kentucky, and Tenissee, and to sell out said rights in portions they shall think best. Now if the above obligors shall in capacity of Attorneys to said obligee faithfully comply with, and not surpass, the power vested in us by the said Letters of attorney in the use of the name of our said Constituent shall not sell said patent right in any other place of Territory distinctly than we are authorized to do by force of said Letters patent of attorney and in as said obligors do and shall diligently and carefully at such proper and Convenient Seasons of the year exert themselves personally or by there agents

(page break)

during the term of said patent right that is for fourteen years next after the fifteenth day of July one thousand Eight hundred and nine to sell and dispose of said patent right under and conformably to said powers of attorney and do and shall annually each and every year in the month of September or October during the term of said patent for fourteen years render or cause to be rendered there just and reasonable accounts of and pay over all the monies, goods, or other things which shall obligors or either of them shall or may have received or obtaind security for, or be entitled receives for said patent right, deducting from said monies, goods, notes, or other things which may be secured or received or to which they may be entitled in full of all Claimes or demands against said obligee thirty three and one third per cent of all which shall be received or to which obligors shall be entitled, in the States of North Carrolina and South Carolina and moiety or half of the residue viz the proceeds from the sailes (sales) in the other States, which acount and payment to be rendered to said obligee, his exceters (executors), or assigns provided in case of remittance in goods said obligee is to bear his charges of freait (freight) and incident expences thereon. Now if the said obligors shall well and timely comply with and fullfill each and every part of the forgoing conditions, then said obligation shall become void and of no affect, otherwise to be and remain in full force power and virtue in the Law."

during the term of said patent right that is for fourteen years next after the fifteenth day of July one thousand Eight hundred and nine to sell and dispose of said patent right under and conformably to said powers of attorney and do and shall annually each and every year in the month of September or October during the term of said patent for fourteen years render or cause to be rendered there just and reasonable accounts of and pay over all the monies, goods, or other things which shall obligors or either of them shall or may have received or obtaind security for, or be entitled receives for said patent right, deducting from said monies, goods, notes, or other things which may be secured or received or to which they may be entitled in full of all Claimes or demands against said obligee thirty three and one third per cent of all which shall be received or to which obligors shall be entitled, in the States of North Carrolina and South Carolina and moiety or half of the residue viz the proceeds from the sailes (sales) in the other States, which acount and payment to be rendered to said obligee, his exceters (executors), or assigns provided in case of remittance in goods said obligee is to bear his charges of freait (freight) and incident expences thereon. Now if the said obligors shall well and timely comply with and fullfill each and every part of the forgoing conditions, then said obligation shall become void and of no affect, otherwise to be and remain in full force power and virtue in the Law."

"Signed sealed and delivered in the presents of Elijah Worthington

Testes

James Warren [Witness?]

William Warren Junr."

Whether the sales of the double-podded auger ever lived up to the expectations of the men involved remains an open question.

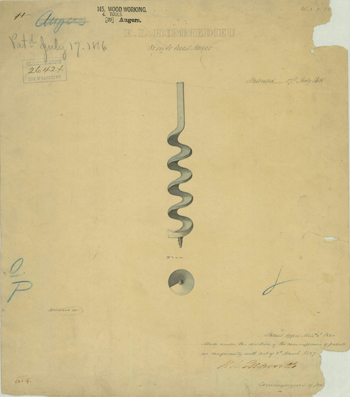

The single-twist auger

In 1812, Ezra L’Hommedieu went into business with his brother Joshua (who may have been a shipsmith) and built a factory on leased land at Pattaconk Brook in nearby Chester for the manufacture of augers and gimlets.(7) Four years later, Ezra patented his truly revolutionary single-twist auger. The bits were formed by wrapping heated bar stock around a mandrel. The U. S. Navy became a major customer, buying the bulk of the early production—as many as 8,000 units per year.(8) According to L'Hommedieu:

In 1812, Ezra L’Hommedieu went into business with his brother Joshua (who may have been a shipsmith) and built a factory on leased land at Pattaconk Brook in nearby Chester for the manufacture of augers and gimlets.(7) Four years later, Ezra patented his truly revolutionary single-twist auger. The bits were formed by wrapping heated bar stock around a mandrel. The U. S. Navy became a major customer, buying the bulk of the early production—as many as 8,000 units per year.(8) According to L'Hommedieu:

This auger has but one that cuts the timber, plant, etc., and but one twist or spiral thread and but one spiral cavity and may be used with or without a screw or worm at the cutting end. ... The advantages of the single twist auger are that the cavity for the chips is larger than in the common twist auger and the form of it is such that the chips pass up more freely and are not crowded together as in the common twist and pod augers. ... and the auger never needs taking out to clear out the chips until after the whole spiral cavity is below the surface of the timber, and the longer the twist of the auger or spiral cavity the deeper it may be bored without clearing. This auger will turn as easily at the depth of two feet (if the twist be so long) as when first entering the surface of the wood.(9)

L'Hommedieu's claims of efficiency for the single-twist auger proved to be accurate. Its hollow center facilitated the passage of large chips up the length of the spiral without clogging, making it ideal for boring deep holes. As per his patent, the L'Hommedieu operation manufactured augers with and without a center screw. Single-twist augers without center screws are often referred to as "barefoot augers" and excel in situations where the workman wants to bore deep but doesn't want the bit to follow the grain of the wood. For this reason, they were often used when drilling into end grain. L'Hommedieu's single-twist design, wildly successful, came to be referred to as a ship auger—a term that remains in use today.

A move, more patents, and a fire

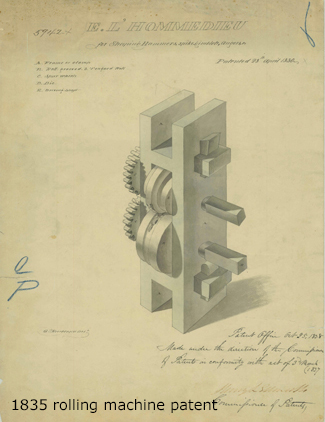

In September of 1830, the L'Hommedieu brothers purchased a building a quarter mile west of their original factory. Built in 1790, the two-story structure was 52 feet long and 35 feet wide and had served as the Peter Spencer iron works and later as the Arthur Snow and Joshua Smith anchor forge.(10) The United States Patent Office issued two patents to Ezra that year: one for a rolling machine to make stock for hammers, gimlets, and augers, and another for shaping and twisting the worm of a single twist auger.

In September of 1830, the L'Hommedieu brothers purchased a building a quarter mile west of their original factory. Built in 1790, the two-story structure was 52 feet long and 35 feet wide and had served as the Peter Spencer iron works and later as the Arthur Snow and Joshua Smith anchor forge.(10) The United States Patent Office issued two patents to Ezra that year: one for a rolling machine to make stock for hammers, gimlets, and augers, and another for shaping and twisting the worm of a single twist auger.

In 1835, the Office awarded him the rights to seven lip and spur configurations for double and single-twist augers in a single patent. The records for the patents,(11) along with those for his 1812 and 1816 augers, were lost in the Patent Office fire of 1836.

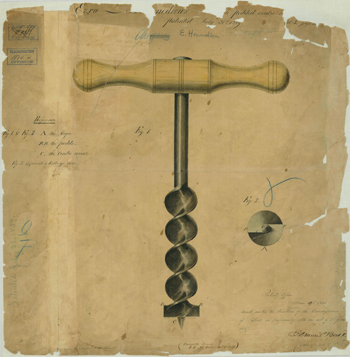

The fire destroyed the documentation for the 9,947 patents issued to that date. Congress responded by passing the Patent Act of 1837. The Act declared the destroyed patents invalid unless the rights holders submitted their original documents or certified copies of them to the Patent Office. Upon receipt, the documents were transcribed and when possible, the Patent Office artists recreated the original artwork that accompanied the patent application. The artwork then became the basis for the line drawings found in official Patent Office publications. The United States Congress ended the effort in 1847 when it disappropriated the funding. By that time, employees had recreated 2,845 of the destroyed patents.

Ezra L'Hommedieu re-submitted the information for his lost patents. Unfortunately, the drawing accompanying the patent for his 1835 patent for auger lip and spur configurations was either lost or not copied. The transcribed text of the patent has survived, but without the drawings, the description of the augers is inadequate to give any more than a skeletal idea of his intent.

In 1838 Ezra L'Hommedieu patented a T-handled gimlet which may not have been manufactured and co-patented a machine for making double-twist augurs with Richard N. Watrous. Both patents were issued in 1838. At some point, Watrous assigned his rights to the augermaking machine to L'Hommedieu who had the patent reissued in 1845, most likely to have his name firmly associated with it.(12) At age 82, he patented his last invention, a die for making augers.(13) The year was 1854.

Deaths, an estate, and a mystery

Ezra L'Hommedieu died of typhoid fever in 1860 at age 88. Just how actively involved he was in his business at the time of his death is a matter of speculation. One writer suggested that his son-in-law, Samuel C. Silliman, may have managed the company for the elderly L'Hommedieu, though the evidence is slim.(14) S. C. Silliman was indeed involved in auger manufacture, but as the principal of S. C. Silliman & Company, producers of ship augers.(15) More likely is that L'Hommedieu's younger brother Joshua took up the slack. A passage on page 368 of Volume 13 of the Chester probate records indicates Ezra L'Hommedieu and his brother Joshua remained equal partners in the company they founded:

Ezra L'Hommedieu died of typhoid fever in 1860 at age 88. Just how actively involved he was in his business at the time of his death is a matter of speculation. One writer suggested that his son-in-law, Samuel C. Silliman, may have managed the company for the elderly L'Hommedieu, though the evidence is slim.(14) S. C. Silliman was indeed involved in auger manufacture, but as the principal of S. C. Silliman & Company, producers of ship augers.(15) More likely is that L'Hommedieu's younger brother Joshua took up the slack. A passage on page 368 of Volume 13 of the Chester probate records indicates Ezra L'Hommedieu and his brother Joshua remained equal partners in the company they founded:

An undivided half interest in the Co. property under the name E. L'Hommedieu, said property being owned & held equal by the said E. L'Hommedieu and Joshua L'Hommedieu and subject to the indebtedness of said partners as owners.(16)

The probate record contains an inventory of the deceased's property divided into two categories: one for personal assets and a second that provides a complete inventory of his partnership's assets of which Ezra L'Hommedieu owned one-half. The firm's major assets included the "Factory and Water privilege & All Buildings South of the P. Brook (Pattaconk Brook) East of the dam," two dwelling houses, and an office building. Among the other items included in the company inventory were 35 tons of hard coal, 1,879 finished augers, bundles of common dimensional iron, and quantities of hammered iron, Sweeds (Swedish) iron, and German steel.

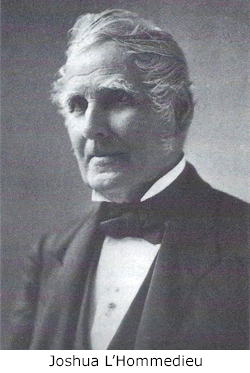

Joshua L'Hommedieu was 73 at the time of his brother's death. While he may have made augers alongside his brother early on, at heart he was a businessman, more interested in politics and the affairs of the town than in managing an auger factory. L'Hommedieu invested in local real estate and several area businesses. His financial acumen is witnessed by his service as a director of four area banks and as president of two. He served five terms as a representative in the Connecticut General Assembly and one as state senator. It is unlikely Joshua spent much time in what amounted to an oversized blacksmith shop.

In 1865 Joshua leased the L'Hommedieu factory and non-specialized equipment to Marvin & Company, a manufacturer of "warps and the like," for the manufacture of cotton goods. The lease stipulated that the leaseholder would not use the facility or equipment to manufacture ship augers or bits. When the lease expired, Marvin & Company moved out and Pond's Extract Company moved in. Pond's Extract used the building to distill the locally abundant witch hazel for use in patent medicines.(16) In 1879, the L'Hommedieu family sold the factory building to Henry L. Shailer, the manager of the Russell Jennings Company. Joshua L'Hommedieu died the following year at the age of ninety-three.

What happened to the L'Hommedieu-branded auger and bits immediately after Joshua L'Hommedieu leased the factory to Marvin & Company remains a mystery. A newspaper article appearing in the Meriden Journal in 1926 does much to muddy the situation.(17) The writer erroneously reports the original L'Hommedieu factory was located in South Meriden and confuses events occurring at that location with the on-the-ground situation in Chester. The L'Hommedieu brand had value. Although a federal trademark law had yet to exist, the use of an established brand name was commonly protected by case law in state courts. Joshua L'Hommedieu's decision to retain ownership of the factory's specialized augermaking equipment and his prohibition on using the factory for auger production suggest that he intended to sell the brand and equipment.

Coincident with Joshua L'Hommedieu leasing the family factory to Marvin & Company, Edward H. Tracy purchased the Eagle Auger And Skate Company factory in South Meriden from the New York hardware distributor Clark, Wilson & Company. (A relationship between the events has not been established.) There he began manufacturing bits bearing the stamps "L'Hommedieu" and "E. H. Tracy."(18) In 1880 he organized the L'Hommedieu Tool Works. L'Hommedieu Tool was not destined for a long life. Neither was E. H. Tracy. In poor health, he was advised to get his affairs in order.

Tracy responded to his doctor's recommendation by associating with C. E. Jennings and Francis B. Griffin in 1881 to incorporate his business as the L'Hommedieu Hardware Company. Tracy retained a controlling interest in the operation.(20) After Tracy's death in 1882, the company reorganized as the Jennings & Griffin Manufacturing Company. It sales were handled by C. E. Jennings & Company in New York. L'Hommedieu branded bits remained in production into the 1920s.

Illustration credits

- Shipyard scene: unsourced public domain image.

- Reconstructed United States Patent Office drawing of double pod auger "made under the direction of the commissioner of patents in conformity with act of 3rd March 1837." Drawing dated June 19th, 1845.

- 1810 bond manuscript: author's photos

- Reconstructed patent drawing of single twist auger "made under the direction of the commissioner of patents in conformity with act of 3rd March 1837." Drawing dated made March 20th, 1840.

- Hand-forged L'Hommedieu augers: author photos.

- Reconstructed patent drawing of roller machine "made under the direction of the commissioner of patents in conformity with act of 3rd March 1837." Drawing dated October 25th, 1838.

- Portrait of Joshua L'Hommedieu: Kate Silliman's Chester Scrapbook.

References

- "The American Screw Auger." The Chronicle of the Early American Industries Association. Vol. 64, no. 3 (September 2011), p. 89-107.

- Historic Buildings of Connecticut. https://historicbuildingsct.com/grover-lhommedieu-house-1799(viewed February 24, 2024).

- At the time, Saybrook included Essex, Deep River, Westbrook, and Chester.

- Bayles, Richard M. “Town of Essex,” in: The History of Middlesex County, Connecticut with Sketches of its Prominent Men. New York : J. H. Beers & Co., 1884. p. 358.

- United States Letters Patent No. 1114X.

- Bishop, Leander J. A History of American Manufactures from 1680 to 1860. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Edward Young & Co., 1868. p. 145.

- Silliman, Samuel C. “Town of Chester,” in: The History of Middlesex County, Connecticut with Sketches of its Prominent Men. New York : J. H. Beers & Co., 1884. p. 224.

- Field, David D. Statistical Account of the County of Middlesex in Connecticut. Middletown, Connecticut : published by the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences : printed by Clark and Lyman, 1819. p. 92.

- United States Letters Patent No. 642X.

- Silliman, Kate. Kate Silliman's Chester Scrapbook. Chester, Connecticut : Chester Historical Society, 1986. p. 148.

- United States Letters Patent 5942X; United States Letters Patent 6142X; United States Letters Patent 8632X.

- United States Letters Patent 627; United States Letters Patent 851 reissued as RE72.

- United States Letters Patent 11,613.

- Corrigan, David J. "Boring Made Easy." Hog River Journal, v. 7, no. 2, (spring 2009), p. 24.

- Silliman, Samuel C. “Town of Chester,” in: The History of Middlesex County, Connecticut with Sketches of its Prominent Men. New York : J. H. Beers & Co., 1884. p. 224.

- Chester Probate Records. Vol. 13, 1851-1867. p. 358-362.

- Silliman, Kate, p. 148.

- "Jennings & Griffin Co. Still Making Augers in Shop Built in 1818." The Journal (Meriden, Connecticut), April 17, 1926. p. 24. The article is more reliable for events taking place from the mid-1860s onward.

- Nelson, Robert E., editor. Dictionary of American Toolmakers. Early American Industries Association, 1999. p. 794.

- "Mr. Tracy's Death." The Meriden Republican (Meriden, Connecticut), February 14, 1882. p. 2.