Russell Jennings

Stephen Jennings

On, March 7, 1836, thirty-one-year-old Stephen Jennings leased a mill and waterpower from George Reed at Bushnell’s Falls, in Deep River, Connecticut, and began making augers. A short eighteen months later, his business became the basis for the organization of the Deep River Manufacturing Company, an enterprise where Jennings served as general manager, John Marvin as president, and Joseph H. Mather as secretary. Other stockholders included Alanson H. Hough, George Reed, and David Watrous.

One of the products manufactured by the Deep River Firm was a double twist, single-spur V-lip auger. Though an example stamped with the company’s name and the word “PATENT” is known, no record of a patent has been located. The documentation may have been among those destroyed in the 1836 Patent Office Fire.

The Panic of 1837 put the Deep River Manufacturing Company in desperate financial straits. Half the banks in the United States closed, bringing business activity to a virtual halt. Sales plummeted. An inventory of unsold bits built up and in 1840, a catastrophic fire destroyed both merchandise and factory. The company’s fire insurance policy is said to have lapsed a day earlier.

On November 6, 1840, the officers of the Deep River Manufacturing Company threw in the towel and quitclaimed the property to Stephen Jennings. The depression that had begun with the Panic of 1837 still lingered, and Jennings struggled to keep the business going. On February 24, 1842, he sold the property to his brother Russell for one thousand dollars. Presumably, Stephen had built a shop to replace the building lost in the fire, for in addition to the three-acre property, the transaction included a structure as well as the dam, water wheels, and manufacturing equipment.(1)

On November 6, 1840, the officers of the Deep River Manufacturing Company threw in the towel and quitclaimed the property to Stephen Jennings. The depression that had begun with the Panic of 1837 still lingered, and Jennings struggled to keep the business going. On February 24, 1842, he sold the property to his brother Russell for one thousand dollars. Presumably, Stephen had built a shop to replace the building lost in the fire, for in addition to the three-acre property, the transaction included a structure as well as the dam, water wheels, and manufacturing equipment.(1)

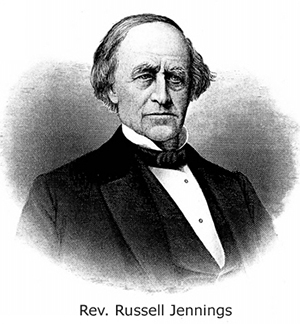

Russell and Stephen Jennings were Baptists and came of age during a period of fervent religiosity known as the Second Great Awakening. Revival meetings and the emotional display of religious fervor were the order of the day. In keeping with the spirit of the times, Russell Jennings became a minister and preached a revival in Winthrop, Connecticut, as early as 1829. He held a half dozen pastorates before moving to Deep River in 1840 to take a position as minister of the local Baptist Church.

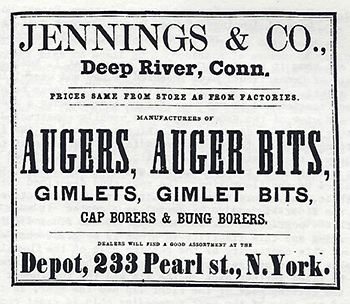

Though Russell Jennings played no role in the management of the Stephen Jennings operation, the firm’s new name, Jennings & Co., reflected the extent of his investment in the business. The enterprise struggled. At one point in the mid-1840s, the business was four months behind in paying its workers.(2) Russell Jennings found himself increasingly involved in the affairs of the company. He resigned his pastorship and purchased the parsonage in 1844. He continued his ministry in a non-pastoral role, preaching at the Baptist congregation in Haddam most Sundays until nervous prostration forced him to rest. After his recovery, Jennings remained active in Baptist affairs, substituting at local churches and preaching the gospel for the rest of his life.

When Stephen Jennings died in January of 1851, his estate was all but insolvent. The business limped along until 1853 when Russell Jennings bought the remainder of the operation from his brother’s estate and assumed its indebtedness. Though he was now the sole owner of an auger-making operation, the transaction nearly bankrupted him. By the time the dust had settled, Russell Jennings’ liabilities exceeded his assets by $15,000.(2)

Russell Jennings 1851-1885

Jennings & Company was a family affair. Jennings installed his 21-year-old son Stephen R. as manager of day-to-day operations. Production centered on gimlets and larger augers used for rough carpentry. The business operated informally. Frank J. Mather recalled working for the Rev. Russell Jennings in the mid-1850s:

He was my true friend when I needed one and my first employer for wages. When I wanted to go to Suffield (a Baptist academy), my father’s circumstances, owing to prolonged illness, forbade him to help me. I saw no better way than to go to work for the Elder. At that time the handling of gimlets and packing were all done in the ell-building of his residence, and I was taken on with my headquarters there. About five o’clock I usually drove to the factory to bring in the day’s work. There the bits were packed and boxed, and I had to take them to the wharf for shipment on the steamboat to New York. So, I usually worked from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. I got seven cents an hour and averaged thirteen hours a day. I was not over fourteen or fifteen then and ninety-one cents a day to me was a big sum. I have been paid better prices since then for work, but I recall no compensation that seemed to me so great as that did then.(3)

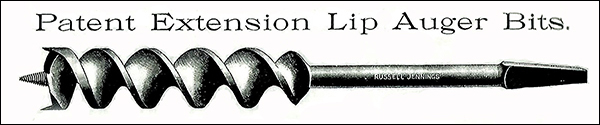

Just how long it took to develop the famous Russell Jennings extension-lip bit is an open question. The elder Jennings was a hands-on owner who learned to operate his factory’s equipment, but he was a minister by trade, rather than a mechanic. His learning curve must have been substantial. Though historian Kenneth Roberts has suggested the origins of the extension-lip bit may owe as much to Stephen Jennings as to his brother, Russell Jennings was a remarkable, if somewhat eccentric, man of ability. It is hard to believe he did not play the lead role in the development of the enterprise’s extension-lip auger bit a full four years after his brother's death.(4)

The Patent Office issued Russell Jennings United States Letters Patent No. 12,318 for the extension-lip bit on January 30, 1855, but it would take almost a decade for the business to produce enough of them to meet demand. The bits were hand-forged, an expensive, laborious process that frustrated all of Jennings’ attempts to achieve economies of scale.

After the award of the patent, the health of Jennings’ son Charles began to deteriorate, forcing the younger man to give up his managerial responsibilities. He died of consumption on June 1, 1859. Russell Jennings hired his daughter’s husband, Henry L. Shailer, to oversee the operation. Shailer, who had been with the concern since the days of Stephen Jennings, proved an excellent, mechanically-minded manager.

The death of his son may have been a factor in Russell Jennings' decision to change the name of the business. His brother Stephen Jennings had been dead for some time, and Henry Shailer was an employee, not a stockholder. If there were other investors, their stake was minor. For all practical purposes, the business had become a sole proprietorship, and the name Jennings & Co. no longer fit. The Rev. Russell Jennings began marketing operation’s products under his own name.

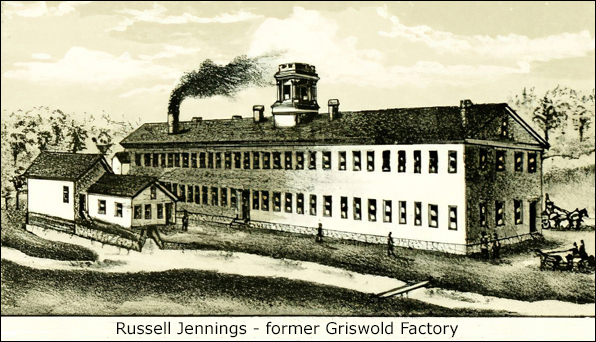

Sales of the operation's augers improved and in 1864, Russell Jennings finally retired the massive debt he had taken on to acquire his brother’s business. Not one to let grass grow under his feet, the following year Jennings began making augers at the former Turner & Day factory on the south fork of Pattaconk Brook in Chester, a village three miles from Deep River. The site's primary structure, a two-story built in 1854 and originally home to the auger-making business of George G. Griswold, was relatively new and in good shape. Topped with a cupola housing the factory bell, two hundred-twenty feet long and twenty-eight feet wide, the two-story structure dwarfed the Jennings shop in Deep River. Jennings retained his original factory, carrying on business at both sites.(5)

It is likely Jennings and his manager Henry L. Shailer collaborated in the behind-the-scenes work that resulted in the three patents awarded to Russell Jennings in 1866.(6) The patents protected a swaging machine, dies for the swaging of auger bits, and a hob for cutting the bits’ throats. The swaging machine, dies, and hob enabled the firm to meet the demand for its primary product and played a major role in the transformation of a modest business into the era’s leading manufacturer of auger bits.

A patent case argued a dozen years later reveals development work on the swaging machine began in 1859 and ended in 1865. It also sheds light on the scale of the manufacturing operation, Russell Jennings’ hands-on involvement, and the secrecy surrounding the machine’s development. Judge William Shipman’s decision upheld Jennings’ right to the patent and noted that Russell Jennings:

… had a contract to deliver three hundred bits of different sizes per day but was unable to finish that number. During nearly each month from February 1859 to 1865, in the intervals of his experiments, he headed bits on the machine, which when made perfect, were delivered with the hand-made bits, upon his contract.

The plaintiff (Jennings) usually operated the machine himself, but some of his workmen, who were sufficiently skilled, occasionally worked on it also. … Its construction was kept secret. It was necessarily used in a room where there was a forge and where there were other workmen, but the public was excluded, and the workmen were warned of the approach of strangers by the ringing of a bell which communicated with another part of the factory. When the machine was not used, it was covered with a cloth.(7)

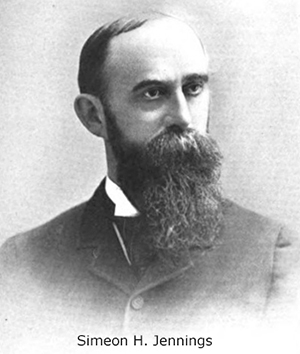

In May 1867, Simeon H. Jennings, Russell Jennings’ nephew, took over sales and the general management of finances. The younger Jennings’ contributions, coupled with those of Henry Shailer, freed sixty-seven-year-old Russell Jennings from much of the drudgery of operating the business. Now well-to-do, Russell Jennings began making substantial financial gifts to Baptist churches and organizations. His ability to do so got a significant boost in 1869 when the United States Patent office extended the patent covering his lucrative 1855 auger design for an additional six years.

The final expiration of the patent in January 1876 presented a problem for the business. Though Russell Jennings manufactured a variety of augers, most were variations of the same design—a cutting head featuring a pair of extended spurs and a finely threaded lead screw. In December 1875, Jennings applied to the Patent Office for an early form of trademark protection known as label registration. The application was approved, giving the business the exclusive right to use the term “Extension-Lip Spur Auger Bitts” on its labels.(8) Though the business would use the term on its boxes for decades, there was little it could do to stop a horde of competitors from copying its distinctive bits.

Undeterred, the Jennings operation made a major investment in its Chester site in 1875 when it built a new factory. The structure was one hundred twelve feet long, thirty feet wide, two stories high, and powered by a twenty-five-foot water wheel. The new building allowed the business to continue the transfer of manufacturing operations to Chester, a project begun in 1865 when it purchased the former Griswold factory.

Between 1869 and 1884 company manager Henry L. Shailer patented six auger-related designs independently of the business he worked for. Three of them were awarded in 1878. Though none were successful, he may have had ideas about striking out on his own. In 1879, he bought the factory once owned by the pioneering American auger maker Ezra L’Hommedieu. Shailer's plans for the two-story building must not have worked out, for in 1881 he sold the property to the Russell Jennings operation.(9) Jennings doubled the footprint of the 15 x 52 feet building, rebuilt the dam, and installed a turbine water wheel. The property became known as the West Shop.

By 1884, the concern operated four factories, three in Chester and one in Deep River. Employing employed forty-two men, the business worked twelve trip hammers. Henry L. Shailer supervised the manufacturing operation, and Simeon H. Jennings served as company attorney and business manager from his office in Deep River.(10) Russell Jennings was now eighty-four years old, and just how involved he was in the business at this time is an open question, but a price list published by the company that year listed him as "Inventor and Proprietor."(11)

Early Tang Stamps

Like any number of nineteenth-century auger makers, Russell Jennings stamped his name on the four-sided tangs of his auger bits. His name typically appeared on the shanks of his bits as well. The wording of the tang stamp changed over time, by examining the variations, it is possible to get some idea of when a bit was manufactured—though it is well to remember changes to stamps often lagged historical events. Much credit goes to George Langford for his early work on the topic.(12)

- Type 1.

- Extension lip auger bits marked “JENNINGS & CO.” and "CAST STEEL" on one side of the tang and “PATENTED JAN. 30, 1855” on another represent the earliest of the operation's patented auger bits—those manufactured between 1855 and ca. 1859.

- Image is courtesy Mem Dubugee.

- Type 2.

- Extension lip auger bits marked “R. JENNINGS” and "CAST STEEL" on one side of the tang and “PATENTED JAN. 30, 1855” on another represent patented bits manufactured between ca. 1859 and the patent extension in 1869.

- Image is courtesy George Langford.

Type 3.

Type 3.- Extension lip auger bits marked “R. JENNINGS” and "CAST STEEL" on one side of the tang and “PATENTED JAN. 30, 1855” and “EXT’D 7 YRS.” on another represent patented bits manufactured between the patent extension in 1869 and its expiration in 1876.

- Author's photo.

Type 4.

Type 4.- Extension lip auger bits marked “R. JENNINGS” and "CAST STEEL" on one side of the tang and no patent dates on another represent bits manufactured between the expiration of the extended patent in 1876 and the co-partnership formed in 1885.

- Image is courtesy George Langford.

Type 5.

Type 5.- Extension lip auger bits marked “R. JENNINGS MFG. CO.” and "CAST STEEL" on the tang represent bits manufactured between the formation of the co-partnership in 1885 and the abandonment of tang stamping ca. 1900.

- Author's photo.

Type 6.

Type 6.- Tang stamps return.

- Extension lip auger bits marked “RUSSELL JENNINGS" on the tang represent bits manufactured between ca. 1938 and ca. 1944.

- Author's photo.

Russell Jennings Manufacturing Company, 1885-1905

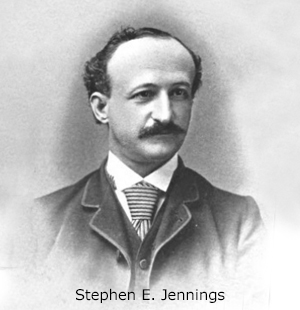

In 1885 the business became a co-partnership but remained a family affair. Simeon H. Jennings, Russell Jennings' nephew, served as president and treasurer; Henry L. Shailer, Russell Jennings' son-in-law, as vice president and general manager; and Stephen E. Jennings, Russell Jennings nephew and son of founding augermaker Stephen Jennings, as secretary. The name Russell Jennings appears nowhere on the list of partners, and the business began to refer to itself as the Russell Jennings Mfg. Company.

How the new partners acquired their stakes in the operation remains a matter of speculation. It appears that Russell Jennings had retired from the business with his health intact and continued to pursue his philanthropic activities. Though there is an unconfirmed report that he married a woman fifty years his junior in 1882, there is no evidence to indicate that he was anything lucid until he suffered a paralytic stroke in September 1887.(13) An invalid afterward, he died on March 6, 1888. Wilbur Wirt Jennings, the grandson of founding augermaker Stephen Jennings, served as the executor of the estate.

Simeon Jennings began acting strangely the summer after Russell Jennings' death. He bought property for which he had no use, moved his house to a poorer location on the opposite side of the street, began selling real estate at a significant loss, and he began thinking of himself as a poor man. Though local citizenry thought his behavior "decidedly queer," that fall they elected him to a term as their representative to the Connecticut General Assembly where he "seemed to be anxious to let his voice be heard on all occasions." A local newspaper reported in an article titled "The Insane Legislator":

Simeon Jennings began acting strangely the summer after Russell Jennings' death. He bought property for which he had no use, moved his house to a poorer location on the opposite side of the street, began selling real estate at a significant loss, and he began thinking of himself as a poor man. Though local citizenry thought his behavior "decidedly queer," that fall they elected him to a term as their representative to the Connecticut General Assembly where he "seemed to be anxious to let his voice be heard on all occasions." A local newspaper reported in an article titled "The Insane Legislator":

Another of his delusions is that he has discovered an infallible remedy for the cure of pneumonia. He had caused the same to be advertised extensively and trusts the preparation to no one but himself.

Last week while on a visit home his insanity became apparent to all. He roamed aimlessly about and tried to impress on everybody he met how his new medicine had healed him from all bodily ill. On Sunday he visited both churches in town, talked incoherently, disturbing the meetings, and finally made them both an uncalled for donation of money.

He refused to live with his wife and took up abode with his father. He discharged his office help, paying them all one year's wages in advance, and then removed all his wearing apparel from his home, saying he had no further use for his residence and proposed to burn it up. On several occasions, he imagined himself possessed with great bodily strength and intimated to several persons that he could throw them quite a distance. As yesterday reported that he was taken to a private asylum at Cromwell.(14)

The Jennings partners authorized Russell Jennings' grandnephew Wilbur Wirt Jennings to serve as the interim treasurer while their president/treasurer was incapacitated.(15) In Dr. Hallock's asylum Simeon Jennings was given writing paper and a dummy checkbook to occupy his time. He spent much of his commitment signing imaginary legislation and worthless checks to the tune of $50,000 (the equivalent of 1.6 million dollars in 2022).(16) Jennings remained in the asylum less than a month. The comparatively short duration of his stay and the mention of his "special medicine" suggest nothing so much as a habitual overindulgence in one of the narcotic patent medicines common in the latter 19th century.

Between 1889 and 1892, the United States Patent Office awarded five patents to the Russell Jennings Mfg. partnership. The most significant of these was United States Letters Patent No. 428,396 for a three-tiered wooden box developed by Simeon H. Jennings. Patented in 1890, the box was not introduced to the public until 1892, the year the Irwin Auger Bit Company introduced its pivoting-drawer bit box. Available at no extra charge with the purchase of a set of auger bits, the company declined to make the hardwood box available as a stand-alone item.(17)

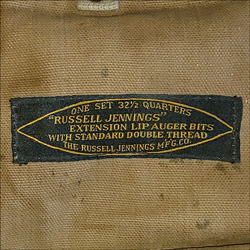

The earliest three-tier boxes featured black interior labels. The earliest of these (pre-1905) list the company's address as Deep River, rather than Chester. Yellow interior labels came later. Save for color, the earliest of these are almost identical to the Chester-issued black labels. A simplified version of the yellow label appeared in the final years of the company's existence as an independent enterprise. The example seen here features the simplified label glued over an old-style yellow label.

The distinctive box became so emblematic of the company that the massive quantity of Jennings bits sold individually and in cloth rolls is often overlooked. Most frequently associated with a standard box of thirteen bits numbered four through sixteen, a boxed set of fourteen bits containing the elusive No. 3 bit is sometimes seen. Other combinations of bits were shipped in cardboard boxes. Two-tier wooden boxes with slots for nine bits became available ca. 1912. In addition to its carpenter's auger bits, the company sold car bits, ring augers, plug bits, machine bits, dowel bits, and augers for hand-cranked boring machines.

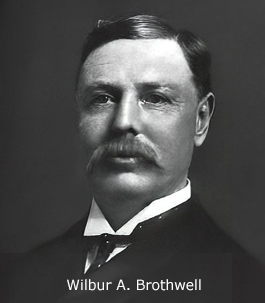

In 1895, the Russell Jennings Company inc., Henry L. Shailer became company president, retaining his position as General Manager. Wilbur Wirt Jennings who settled Russell Jennings' estate and stepped in during Simeon H. Jennings' breakdown, became vice president. Wilbur A. Brothwell, a grandnephew of Russell Jennings who once worked for P. T. Barnum, was elected treasurer. Stephen E. Jennings retained his position as company secretary. Though no longer a company officer, Simeon H. Jennings still owned one-fourth of the operation. He died in 1898, after a year-long illness, of "brain trouble".

The Russell Jennings Mfg. Company sold its Deep River factory in 1903 to Pratt Read & Company, a business that made products from ivory. The plant was not missed as Jennings no longer used the site, having abandoned production there as early as 1890. The Russell Jennings office remained in Deep River until the death of company president Henry L. Shailer.

Though the company sold all manner of bits and augers, the bits designed for use with a hand brace were the stars of the lineup. Standard carpenter's auger bits came in two varieties: the double-threaded No. 101 and the single-threaded No. 100.

- The lead screw on the No. 101 became the company's single thread point. Designed for quick boring, the No. 101's single-thread lead screw did not clog in gummy wood and was effective in extremely hard wood. The company considered the No. 101 as "especially suited to the work of plumbers and electricians."

- Russell Jennings Mfg. called the lead screw of its No. 100 bits a standard double thread point. It considered the bit "unsurpassed for accurate work in seasoned soft wood" and intimated it was "preferred by most cabinet makers."

- Russell Jennings Mfg. also manufactured a seldom-seen bit with an unthreaded square point. Designed for high-speed machine use, the threadless lead did not clog.

- For a brief time, ca. 1913, Russell Jennings manufactured an auger bit with a very coarse lead screw. Suitable only for soft woods, the company referred to the screw as its double quick point. (not illustrated)

A New Generation Takes Over

Company vice president William Wirt Jennings died in 1904, and company president, Henry L. Shailer, a year later at age eighty. Shailer willed his company stock to his nephews Samuel R. and Henry F. Shailer who by this time had taken over supervision of the firm's manufacturing operation. Stephen E. Jennings, son of the Stephen Jennings who had founded the original Jennings auger shop, replaced the elder Shailer as company president.

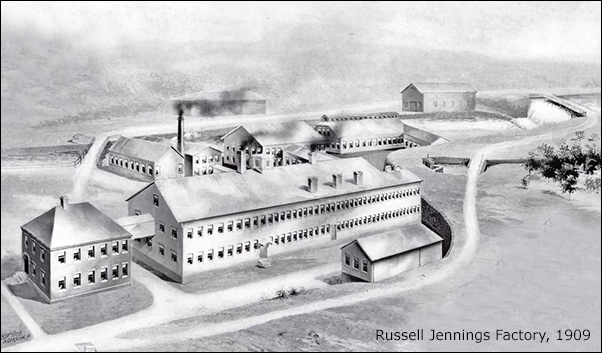

With Deep River resident Henry L. Shailer's passing, there was little reason to keep the company office in its original location. The company moved the office to Chester in 1905 and in March of 1907 formally opened a new brick office building with a handsomely appointed directors' room on the second floor. Business was good. At the time of the opening, the company was booking orders two years in advance and expected its 125 workers would produce one million bits every twelve months.

Though the company was doing well, trouble was brewing in paradise. The Russell Jennings Mfg. Company's stock, once closely held, was now in the hands of a larger group of shareholders—many of them unhappy with earnings and believing the firm was not innovative enough. At the July 1909 stockholders meeting, those present "retired" secretary/treasurer and general manager William A. Brothwell. Production managers Samuel R. and Henry F. Shailer lost their positions on the board as well. The new board of directors elected Arthur L. Jennings, the son of Simeon H. Jennings (the "insane" legislator), to serve as the company's vice president and treasurer. Ernest A. Jennings, the son of William Wirt Jennings, became the company secretary. At the same meeting, the board hired Arthur F. Blasdell, the superintendent of the Westinghouse Machine Works, to replace production managers Samuel R. and Henry F. Shailer.(18)

Though The Hartford Courant referred to the changes as a "sudden shakeup," the temporary absence of the powerful William A. Brothwell at the time of the vote suggests he knew the outcome in advance and did not wish to be present for it. That the board announced the hire of the superintendent to replace the two Shailers that same day gives credence to the idea that the plan to remove the three directors had been in the works for some time.

Arthur F. Blasdell, the superintendent who replaced the Shailers, moved to Chester but did not stay long. Two and one-half years after his arrival, he relocated to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, to take a job with the General Electric Company where he became plant manager. It is, perhaps, inevitable that he moved on. Prior to taking the job in backwater Connecticut with Russell Jennings, he'd been superintendent of a works in Pittsburgh with a floor space of 20.4 acres and three thousand employees. The plant manufactured The Westinghouse-Parsons steam turbines, Corliss steam engines, and Westinghouse gas engines. Russell Jennings, a much smaller company, manufactured a single product—auger bits.

Arthur L. Jennings and Arthur Blasdell worked to expand the operation's product line with a foray into the manufacture of bit braces. The company acquired the rights to manufacture chucks based on a tool handle patented in 1904 by Isaac Sherwood Davidson of Kansas City, Missouri.(19) Davidson's chuck accepted bits with slotted tangs and corrected the inevitable wobble that occurs when the jaws of a chuck fail to align with the tapered sides of a traditional auger bit's four-sided tang. A protruding key at the bottom of his chuck accepted the slotted tang, a connection that made for a tight and rigid fit. The company began marketing braces with the design in 1911, referring to it as a Precision Chuck and stamping Davidson's 1904 patent date on it.(20)

The downside of Davidson's chuck was that it did not accommodate the standard four-sided tang used on most auger bits, a limitation that rendered existing bits in a worker's toolbox obsolete. To solve the problem, Russell Jennings Mfg. developed a brace with a Universal Precision Chuck, a variation of Davidson's design that accepted both the traditional and slotted tangs. The company introduced both the original and universal chucks at the same time. Arthur L. Jennings applied for a patent to protect the company's new Universal Precision Chuck. Though he made his application in early 1911, the patent was not awarded until 1915.(21) The document also protected a simpler version of Davidson's chuck shown on a bit extension. When the patent was finally issued, the initial enthusiasm that accompanied the 1911 rollout had waned. An example of a Jennings slotted-tang chuck stamped with a date other than that of Davidson's original 1904 patent has yet to surface.

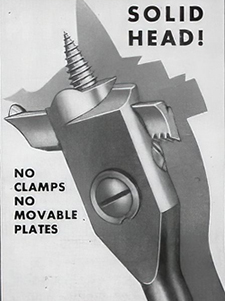

The 1911, slotted-tang roll out included a solid-head expansive bit developed by Russell Jennings Mfg. in 1910 and patented by Arthur L. Jennings in 1911.(22) The new bit featured a cross-feed screw adjustment that controlled a cutter that rode through a channel in the bit's head. Not wanting to limit the market for its new product, the company made its expansive bit available with either a slotted or four-sided tang. The solid-head expansive bit remained in production for decades.

The 1911, slotted-tang roll out included a solid-head expansive bit developed by Russell Jennings Mfg. in 1910 and patented by Arthur L. Jennings in 1911.(22) The new bit featured a cross-feed screw adjustment that controlled a cutter that rode through a channel in the bit's head. Not wanting to limit the market for its new product, the company made its expansive bit available with either a slotted or four-sided tang. The solid-head expansive bit remained in production for decades.

From the beginning, the company made its new tools available individually or in Precision sets. The sets, packed in attractive wooden boxes, included a brace, thirteen slotted shank auger bits, an expansive bit, a bit extension, two screwdriver blades, and countersinks for both wood and metal. Though Russell Jennings made the sets available with either Precision or Universal Precision braces the accessories all featured slotted tangs. Most of the braces were fitted with vulcanized fiber knobs and handles, and at some point, a Precision set with a non-ratcheting brace became available.

Ads for the company's Precision augers and bits touted the accuracy of their turned stems over the imperfection of traditional forged shanks. Just how important the extra accuracy was to the average workman is another matter. Neither bits nor braces set the market on fire. The bits' incompatibility with the standard braces found in most toolboxes proved a limitation not easily overcome. Disadvantages aside, the Jennings slotted-tang tools enjoyed a respectable run. They remained available until the onset of the Great Depression.

November 1913, Arthur L. Jennings, the company's vice president and general manager, traveled to St. Catherines, Ontario, to close on the purchase of a facility for a branch manufacturing operation. Canada's thirty percent duty on bits manufactured elsewhere provided much of the impetus tax for the creation of the satellite operation.(23) The extent of the company's commitment is questionable. The company shuttered the operation in 1915 and reopened again later that year. It closed again soon afterward.

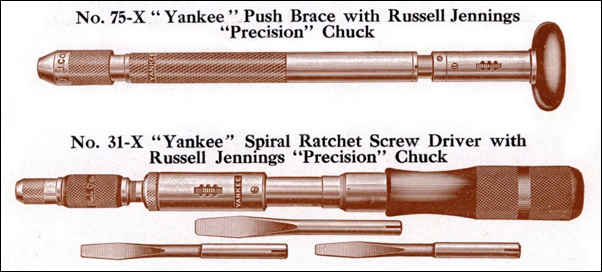

In 1915, Russell Jennings Mfg. released a four-page brochure introducing its new Precision push brace and screwdrivers. Anchoring the line were the No. 75-X push brace and No. 31-X spiral screwdriver, tools manufactured by North Brothers Mfg. and fitted with the Jennings Precision chuck.(24) The "Yankee" tools were not the only products introduced in the brochure. The launch included both interchangeable-blade and standard screwdrivers as well as slotted-tang Forstner, gimlet, and reamer bits. The company made much of the compatibility of its slotted-tang bits across all the tools in its Precision line, though at some point the resistance encountered in boring larger holes with its new push brace rendered the tool impractical. The new tools featured vulcanized fiber handles. The Russell Jennings Mfg. Company's collaboration North Brothers appears to have been short-lived.

By this time, Arthur L. Jennings had replaced Stephen E. Jennings as company president. He purchased a controlling interest in the R. H. Brown Company of New Haven in the fall the new Yankee/Jennings push-tool line was announced. A short time later, three carloads of R. H. Brown machinery arrived at the Chester depot. Jennings planned to set up a business for the manufacture of screwdrivers and expansive bits and intended that the new operation be independent of the Russell Jennings Mfg. Company. The equipment was set up in the West Shop, the facility the firm had purchased from Henry Shailer in 1881.(25) Research has failed to uncover the motivation behind the acquisition though it may be that Jennings hoped to begin the local manufacture of screwdrivers. Though it is likely the new A. L. Jennings enterprise did not prosper, the fate of the endeavor remains unknown.

By this time, Arthur L. Jennings had replaced Stephen E. Jennings as company president. He purchased a controlling interest in the R. H. Brown Company of New Haven in the fall the new Yankee/Jennings push-tool line was announced. A short time later, three carloads of R. H. Brown machinery arrived at the Chester depot. Jennings planned to set up a business for the manufacture of screwdrivers and expansive bits and intended that the new operation be independent of the Russell Jennings Mfg. Company. The equipment was set up in the West Shop, the facility the firm had purchased from Henry Shailer in 1881.(25) Research has failed to uncover the motivation behind the acquisition though it may be that Jennings hoped to begin the local manufacture of screwdrivers. Though it is likely the new A. L. Jennings enterprise did not prosper, the fate of the endeavor remains unknown.

By 1920 Wilbur A. Brothwell had returned to his position as Russell Jennings Manufacturing Company's vice president and general manager, titles he had lost during the 1909 company shakeup. Perhaps the most notable event to take place during the early part of the decade was a failed attempt by the Stanley juggernaut to buy the company. Ethelbert Allen Moore, the president of the Stanley Works, Moore wanted to enlarge his company's product line and hoped to do so by acquiring the maker of "best auger bits in the country." Sadly, the brief mention of the event in Moore's memoir gives no account of the negotiations or the reason the deal collapsed.(26) Wilbur A. Brothwell became company president in the 1920s. He held the title until his death at age seventy. His son, Charles R. Brothwell succeeded him, remaining at the helm until his death in 1940.

A narrow product line and the construction industry's move to electric drills took their toll on the Russell Jennings Mfg. Company. By the early 1940s, the operation employed seventy workers, half the number it did at its peak. In 1944, the Stanley Works again made an offer to purchase the company, and this time it was successful.

Stanley kept the operation in Chester, leasing out the West Shop until 1946 when it demolished the structure due to liability concerns. In 1961 it closed the plant and moved the machinery and production to New Britain. A year later, Stanley sold the Chester factory to Victor Tool who used the facility to manufacture desktop copy machines.

Illustration credits

- Portrait of Russell Jennings: The History of Middlesex County, Connecticut: with Sketches of its Prominent Men. New York : J. H. Beers & Co., 1884.

- Ad for Jennings & Co.: Roberts, Kenneth, ed. Price List: The Russell Jennings Mfg. Co., Deep River, Conn., U.S.A. Williamson, Mass. : Ken Roberts Publishing, 1981.

- Original Russell Jennings factory: courtesy Deep River Historical Society

- Patent extension-lip auger bit: Roberts, Kenneth, ed. Price List: The Russell Jennings Mfg. Co., Deep River, Conn., U.S.A. Williamson, Mass.: Ken Roberts Publishing, 1981.

- The Griswold/Jennings factory view: View of Chester, Connecticut. Boston : O. H. Bailey & Co., 1881.

- Portrait of Simeon H. Jennings: The History of Middlesex County, Connecticut: with Biographical Sketches of its Prominent Men. New York : J. H. Beers & Co., 1884.

- Images of three-tier box and labels: author's photos.

- Auger bit lead screws: Russell Jennings Manufacturing Company. Catalog. no. 30. Chester, Connecticut: Russell Jennings Mfg. Co., ca. 1911.

- Portrait of Stephen E. Jennings. Commemorative Biographical Record of Middlesex County Connecticut: Containing Biographical Sketches of Prominent .... Chicago : J. H. Beers & Co., 1903.

- 1909 factory image: Russell Jennings Manufacturing Company. Catalog No. 30. Chester, Connecticut : Russell Jennings Mfg. Co., ca. 1911.

- Expansive bit ad: unidentified magazine clipping dated September 19, 1939.

- Ratcheting screwdriver and push drill image: "Yankee" Tools with Russell Jennings "Precision" Chucks and Fibre Handles. Chester Connecticut : Russell Jennings Mfg. Company, ca. 1915.

- Portrait of Wilbur Brothwell: Commemorative Biographical Record of Middlesex County Connecticut: Containing Biographical Sketches of Prominent .... Chicago : J. H. Beers & Co., 1903.

- Images of Russell Jennings bit roll and Stanley-Jennings box: author's photos.

References

- Unless otherwise cited, information about the Stephen Jennings years is courtesy of: Knouse, William H. “Town of Saybrook,” in: The History of Middlesex County, Connecticut: with Sketches of its Prominent Men. New York : J. H. Beers & Co., 1884. p. 557-558; and Roberts, Kenneth, ed. Price List: The Russell Jennings Mfg. Co., Deep River, Conn., U.S.A. Fitzwilliam, Mass. : Ken Roberts Publishing, 1981.

- Kebabian, John S. “A Worker’s Account Book, 1845-1849.” The Gristmill. No. 40, June 1985. p. 12.

- Mather, Frank J., Old Deep River: an address delivered by Frank J. Mather. Deep River, Conn : Deep River Library Association, 1914. p. 18.

- Roberts, Kenneth, ed. Price List: The Russell Jennings Mfg. Co., Deep River, Conn., U.S.A. Fitzwilliam, Mass. : Ken Roberts Publishing, 1981. p. 3.

- Silliman, Samuel C., “Town of Chester,” in: The History of Middlesex County, Connecticut : with Sketches of its Prominent Men. New York: J. H. Beers & Co., 1884. p. 224.

- United States Letters Patent No. 55,498; United States Letters Patent No. 56,058; and United States Letters Patent No. 56,869.

- “Russell Jennings vs. E. N. Pierce and Charles E. Andrews.” Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Circuit Court of the United States for the Second Circuit. New York : Baker, Voorhis & Company, 1880. p. 42-46.

- “Labels Registered During the Week.” Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office. Dec. 28, 1875. p. 1077.

- Brothwell, Wilbur H. “The Russell Jennings Manufacturing Company, Inc.: Over a Century of Business.” The Gristmill. No. 40, June 1985. p. 12. Note: Though Brothwell, a lifelong Chester resident, confused the two Charles Jennings living in the area at in the 1850s, the remainder of his article is sound.

- Silliman, Samuel C. “Town of Chester,” in: The History of Middlesex County, Connecticut: with Sketches of its Prominent Men. New York: J. H. Beers & Co., 1884. p. 224.

- Russell Jennings' New Price List of Patent Augers and Extension Lip Auger Bits (broadside). Deep River Connecticut: Russell Jennings, 1884. Reprinted: Early American Industries Association, 1979.

- Langford, George. "Russell Jennings Auger Bits." georgesbasement.com. (viewed December 11, 2022.)

- The undocumented marriage: “News of the State,” Meriden Daily Republican (Meriden, Connecticut). September 25, 1887. p. 1.

- "Insane Legislator." The Journal (Meriden, Connecticut). March 21, 1889. p. 1.

- "His Delusions." The Morning Journal-Courier (New Haven, Connecticut). April 8, 1889. p. 2.

- "Jennings Now Drawing Checks." The Journal (Meriden, Connecticut). March 21, 1889. p. 1.

- Roberts, Kenneth, ed. Price List: The Russell Jennings Mfg. Co., Deep River, Conn., U.S.A. Fitzwilliam, Mass. : Ken Roberts Publishing, 1981. p. 23.

- "Sudden Shakeup in Chester Concern." The Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut). July 10, 1909. p. 2.

- United States Letters Patent No. 753,241.

- "New Auger Bits and Braces." American Carpenter and Builder. November 1911. p. 94, 96, 98.

- United States Letters Patent No. 1,127,007.

- United States Letters Patent No. 1,004,572.

- "Jennings Canadian Factory Will Open in January" Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut). Nov. 4, 1913. p. 20.

- "Yankee" Tools with Russell Jennings "Precision" Chucks and Fibre Handles. Chester, Connecticut : Russell Jennings Mfg. Company, ca. 1915; "Trade Notes." Manual Training and Vocational Education. September 1915. p. XXII.

- "Jennings Buys Bit Factory and Moves it from New Haven to Chester." The Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut). October 31, 1915. p. 2.

- Moore, Ethelbert Allen. Four decades with the Stanley Works, 1889-1929. New Britain? Connecticut : Privately printed, 1950. p. 87.