Connecticut Valley Mfg. Company / CONVALCO

The Falls River is an eight-mile-long tributary of the Connecticut River that runs through the town (township) of Essex for most of its length. It is currently dammed in two locations in the village of Centerbrook, both of which played a role in the history of the Connecticut Valley Manufacturing Company.(1)

The Falls River is an eight-mile-long tributary of the Connecticut River that runs through the town (township) of Essex for most of its length. It is currently dammed in two locations in the village of Centerbrook, both of which played a role in the history of the Connecticut Valley Manufacturing Company.(1)

Samuel A. Smith & Henry C. Lewis

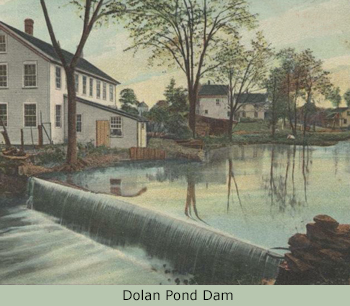

The first of the locations is the impoundment created by the Dolan Pond Dam, a four-foot-tall structure that despite its low stature provided enough energy to power at various times a fulling mill, an ivory products shop, several wood-turning enterprises, and an auger factory—Samuel Smith & Company. Smith and his associates set up shop after purchasing the dam and an adjacent mill building from button manufacturer William Strickland in the mid-19th century. Samuels Smith's enterprise was one of a dozen or so auger manufacturing businesses that set up shop in Middlesex County, an area long associated with the production of bits for the New England shipbuilding industry.

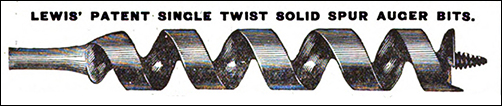

In 1868, Samuel Smith reorganized the company for reasons unknown, taking on New Haven hardware dealer A. H. Kimberly as a partner. The operation, named Smith & Kimberly, operated both the auger manufactory and a retail outlet. The firm was short-lived but is significant in that it acquired the rights to the products of Lewis & Company, a bit maker located just five miles away in the town of Westbrook.(2) Henry C. Lewis, the driving force behind the Westbrook Company, had patented a commercially viable countersink in 1866 and a single-twist auger with a solitary spur in 1869.(3)

Though the Lewis auger bit was destined for commercial success, Smith & Kimberly may not have manufactured it. By September 1869, a few months after the patent issue, the enterprise was no longer in business. A Lewis bit with a Smith & Kimberly mark has yet to surface. Most surviving examples are stamped on the tang with a stamp reading:

LEWIS' PAT.

JUNE 1, 1869

Samuel Smith sold the Lewis patents to the Centerbrook Manufacturing Company shortly after Smith & Kimberly dissolved. The sale may also have included the rights to a combined auger bit and thread tap Smith patented later that fall.(4) He remained in Essex for at least another four years, receiving United States Letters Patent No. 136,391 for a die to form lead screws on auger bits. After selling his patent, Henry Lewis took up farming near Westbrook. The new occupation may not have suited him. By the time of the 1880 census, he had relocated to the nearby village of Clinton and returned to his trade of auger-making. In his later years, he worked for the Russell Jennings Company, an auger bit manufacturer in the borough of Chester.(5)

The Centerbrook Manufacturing Company

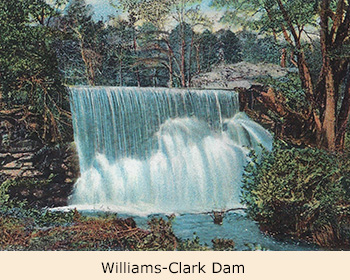

In addition to purchasing the Smith & Kimberly patents, the owners of the newly formed Centerbrook Manufacturing Company acquired the Dolan Pond dam, the mill, and Samuel Smith's equipment for the sum of $10,000. Centerbrook Mfg. moved the operation's trip hammers, water wheels, belting, shafting, anvils, lathes, and grinding tools to a new location at the Williams-Clark Dam several hundred feet upstream.(6)

The Centerbrook Mfg. Company installed Samuel A Smith's equipment in an existing factory it had purchased from Sydney and Lucy Bushnell. The building was one of several businesses situated at the dam, a stone structure spanning a rocky part of the Falls River and holding back a wall of water eighteen feet tall. In its new location, Centerbrook Manufacturing shared the dam's abundant waterpower with a gristmill and sawmill that had been operating at the site since the eighteenth century.

The Centerbrook Manufacturing Company produced augers, gimlets, and bits, presumably those previously manufactured by Smith & Kimberly, marketing them under its own name or that of the C. B. Mfg. Co. The Financial Panic of 1873, a cascading chain of bank and business failures, set in motion an economic depression that led to the insolvency of the fledgling Centerbrook Manufacturing Company.

The Connecticut Valley Manufacturing Company

In February 1874, local businessmen George A. Cheney and Alfred M. Wright organized a company that bought Centerbrook Manufacturing's dam, factory, equipment, and patents at a sheriff's sale.(6) The directors called the new business the Connecticut Valley Manufacturing Company. The name was not particularly original. An earlier and similarly named firm, the Connecticut Valley Hardware Company, had been established in nearby Chester a few years earlier. Research has failed to produce a link between the two.

In February 1874, local businessmen George A. Cheney and Alfred M. Wright organized a company that bought Centerbrook Manufacturing's dam, factory, equipment, and patents at a sheriff's sale.(6) The directors called the new business the Connecticut Valley Manufacturing Company. The name was not particularly original. An earlier and similarly named firm, the Connecticut Valley Hardware Company, had been established in nearby Chester a few years earlier. Research has failed to produce a link between the two.

George Cheney, the Connecticut Valley Manufacturing Company's president, had previously spent twelve years working as an ivory buyer in Zanzibar.(7) On his return to the United States in 1860, he invested in S. M. Comstock & Company, an Essex ivory-cutting company, and prospered. His interest in the Connecticut Valley organization was, for the most part financial, and as his fascination with the affairs of the more profitable Comstock, Cheney & Co. grew, his enthusiasm for involvement in the affairs of Connecticut Valley Manufacturing dwindled.

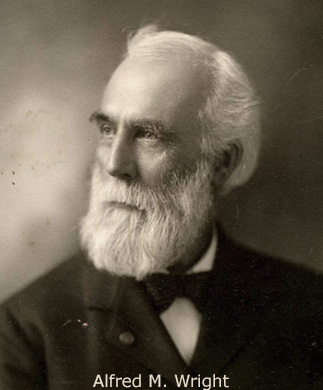

Though Cheney may have been the biggest investor, Alfred Mortimer Wright, Connecticut Valley's treasurer and superintendent, served as the catalyst for the organization of the firm. Having worked as an assessor for the State of Connecticut, he moved to Centerbrook in 1873 after securing an appointment as trustee to settle the affairs of the bankrupt Centerbrook Manufacturing Company. Realizing that the operation's remaining assets were substantial enough to form a new company, he organized a group of investors who succeeded in buying the plant, equipment, and Lewis patents.

The Connecticut Valley Manufacturing Company continued to produce the augers and gimlets formerly manufactured by Centerbrook. The new operation arranged for the distribution of its Lewis auger bits by the Millers Falls Company, an agreement that made Millers Falls sole sales agent for the tool. The arrangement continued through most of the 1880s. The traditional Lewis auger would remain in production through the early 1900s. How long Connecticut Valley Mfg. continued to produce the bit and how long it continued to stamp the Lewis patent date on it are unknown. Lewis-style augers remain popular today.

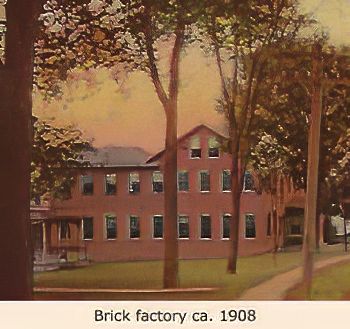

An examination of a ca. 1890 photograph of Connecticut Valley Manufacturing's auger works shows them as less than impressive. At first glance, the factory could be mistaken for a rural farmstead. The buildings are wood frame, rather than brick. A small, tree-shaded house served as the company's office, and its wood-frame production facilities resembled nothing so much as barns. The contrast between the bucolic scene and the often-reproduced images of the prison-like sweatshops of Lowell, Massachusetts is marked. Missing from this view of the auger works is a two-story office built after the photo was taken.

An 1884 county history included this description of the company's works:

The main building is 100 X 25 feet, two stories high; and the forge room is a one-story building. About 70 horsepower is obtained from the stream and the shop employs an average number of 50 hands, most of whom are skilled workmen. The goods are sent to all parts of this and foreign countries.(8)

A few years after the 1890 photo of the Connecticut Valley shops was taken, an event took place that changed the look of the company's facilities dramatically. Wooden buildings are flammable, and housing anything but a small-scale forging operation in one is a recipe for disaster. On March 2, 1894, a watchman discovered a fire in the forging shop. A nearby local newspaper reported:

An alarm was sounded at one and the Essex fire department responded. The roads were so rough and the scene of the fire so distant that the fireman could not draw their apparatus by hand within reasonable time and horses were attached.

The four buildings of the plant consisted of the main building, the forging room, the packing house and the office, the latter having been but recently constructed. All were two-story structures. The firemen attempted to confine the blaze to the forging shop, but without avail. In a short time the packing house and the main building were also in flames. All hopes of saving these buildings were then abandoned and efforts were made to save the stock, by citizens and firemen, which were partly successful. It was only after a heroic effort that the office building was saved.

In the meantime, the adjacent gristmill of Jerome Bushnell had caught fire and in a short time was in ruins. The fire will prove a big loss to Centerbrook. Forty hands were thrown out of employment.(9)

Seven months after the disastrous fire, two substantial brick buildings stood on the site, new machinery had replaced the old, and fifty hands were at work producing auger bits. The Connecticut Valley one-story forging shop measured twenty-five by one hundred feet, and the two-story machine shop, thirty-seven by seventy-two. The plant featured steam heat and utilized both water and steam for power.(10) Not mentioned in the glowing notices of the new plant is the detached forge building situated alongside the mill flume—still made of wood.

Seven months after the disastrous fire, two substantial brick buildings stood on the site, new machinery had replaced the old, and fifty hands were at work producing auger bits. The Connecticut Valley one-story forging shop measured twenty-five by one hundred feet, and the two-story machine shop, thirty-seven by seventy-two. The plant featured steam heat and utilized both water and steam for power.(10) Not mentioned in the glowing notices of the new plant is the detached forge building situated alongside the mill flume—still made of wood.

By March of 1893, American augermakers were producing so many standard augers and bits that they had become a commodity. A soft economy only compounded the problem. A group of ten augermakers responded by forming the American Auger and Bit Association, an organization whose primary purpose was to set prices for various categories of augers, a practice sometimes referred to as price fixing. Connecticut Valley Mfg. became a charter member. Notable among the non-participants were the Irwin Auger Bit Company whose unique designs were protected by patent, and the Russell Jennings Mfg. Company whose bits commanded a premium. The organization remained active for some dozen years.(11)

The Clark knockoffs

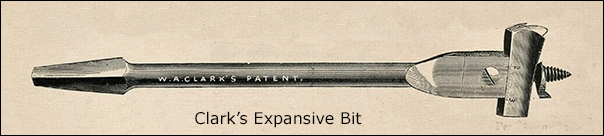

The history of Connecticut Valley Manufacturing was one of making quality bits at less-than-premium-prices prices rather than one of innovative design. In the mid-1890s, the company became one of a plethora of auger makers to produce a version of William A. Clark's expansive bit, a wildly popular bit that could be adjusted to cut holes in a variety of sizes whose patent protection had expired.

The expansive bits were the most successful of W. A. Clark's tool designs. The United States Patent Office awarded him over a dozen patents covering such items as auger and expansive bits, hollow augers, a countersink with pilot, an ice auger, and a meat tenderizer. A man of wide-ranging interests, Clark was a pioneer in the business of making sulfur matches and operated a successful business in Woodbridge, Connecticut, for that purpose. As he transitioned into retirement, his son Frank E. took on the management of William A. Clark & Co. and in 1880 sold the factory building to the newly organized R. A. Brown & Company.

Connecticut Valley's copy of the Clark expansive bit left the officers of R. H. Brown & Company unimpressed. In January 1893, Brown & Company filed for trademark protection on the words "Clark's expansive." The company obtained an injunction against Connecticut Valley Mfg. a few months later.(12) The order enjoined Connecticut Valley from using the word "Clark's expansive" on its packaging. Brown argued that Connecticut Valley was:

making a bit which they were putting on the market as the Clark bit and putting it up (packaging it) in exactly the same fashion as the R. H. Brown & Co.'s Clark bit thereby greatly increasing and decreasing the business of R. H. Brown & Co.(13)

Brown & Company's efforts to protect its new trademark met with limited success. Whether by agreement with R. H. Brown & Co. or the lapse of the 1893 injunction, Connecticut Valley continued making the bit. Other firms joined the rush, and copies of Clark's expansive bit soon flooded the market, virtually all identified by Clark's name.

For a time, the Connecticut Valley Manufacturing Company manufactured a screwdriver developed by William A. Clark's son, Frank E. Clark. The younger Clark had adapted a patent from a dental drill to produce a screwdriver with interchangeable blades.(14) Put up in a tidy wooden box, a set of F. E. Clark's Best Quality Screwdrivers made for an attractive gift and handy item to have around the house. R. H. Brown & Company, a business in which he maintained a substantial financial interest, manufactured and sold F. E. Clark's screwdriver.

After the dentist-drill patent expired, Connecticut Valley Manufacturing began making a version of Frank E. Clark's screwdriver. It is doubtful the company maintained any sort of licensing arrangement with either F. E. Clark or R. H. Brown & Company for the tool as neither name appears on the packaging. Instead, Connecticut Valley chose the stunningly prosaic "Screw Driver Set Number 12" to refer to its new product.

Jennings-style bits

Like most of its competitors, Connecticut Valley Mfg. company made copies of the renowned Russell Jennings extension-lip bit by the tens of thousands and felt free to use the Jennings name. An early ad for the Connecticut Valley's bits appeared in the trade periodical The Iron Age in 1895.(15) Early Jennings-type bits manufactured by Connecticut Valley were stamped:

A. M. WRIGHT'S JENNINGS

Ads picturing bits stamped with the A. M. Wright's Jennings mark appeared in the trade literature from 1895 through 1897. In the first decade of the twentieth century, perhaps at the time of Alfred Mortimer Wright's death, the company shortened the A. M. Wright's Jennings designation added a country of origin. The new stamp, housed in a rectangular octagon now read:

WRIGHT'S JENNINGS

U. S. A.

In 1896, a notice introducing Connecticut Valley's blued version of a Jennings-type bit appeared in the periodical Carpentry and Building.(16) The notice refers to the bits' blue "anti-rust" finish but includes no mention of the Wright's Jennings trademark. The firm's blued bits were not marked with the premium Wright's Jennings designation and represented a second-quality line. Connecticut Valley Manufacturing continued to produce blue-finished bits into the 20th century. The bits were stamped with a broken-cornered rectangle bearing the simple designation:

CONN. VALLEY

U. S. A.

The company originally put up its premium Wright's Jennings bit in what it referred to as its "deluxe box." The box featured a unique hook-and-eye retainer that held the bits in a series of slots cut into a transverse wooden bar. The company eventually abandoned its deluxe box, substituting George H. Bartlett's popular design in its place. Connecticut Valley's blued bits were originally packed in generic American case boxes. The American case utilized individual spring-type clips wood-screwed to a transverse bar to hold bits in place. It was not patented. The company later packed its blued bits in Bartlett boxes.

Irwin-type bits

Like its competitors, Connecticut Valley began manufacturing a solid-center auger bit, after the 1904 expiration of Charles H. Irwin's well-known patent. The company packaged the bits in Bartlett boxes and stamped the shanks with a broken-cornered rectangle bearing the designation:

WRIGHT S

SOLID CENTER

U S A

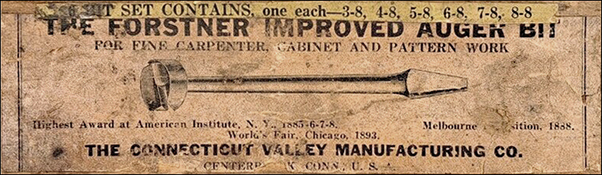

Forstner bits

In the 1890s Connecticut Valley Mfg. Company began marketing a version of Benjamin Forster's renowned circular-lip bit. Forstner, a gunsmith living in Salem, Oregon, had patented the bit on September 22, 1874. His bit featured a sharpened circular band with an internal cutting lip. Fitted with a brad point, rather than a lead screw, it excelled at boring smooth-sided, flat-bottomed holes.(17)

Forstner improved on his bit in 1886 when he bisected the circular band with a pair of angled, milled slots. The angled slots created a pair of internal cutters, reducing the amount of pressure needed for boring. The redesign, easier to sharpen and cheaper to produce, did much to improve the popularity of his invention. He patented his improved design as well.(18)

Benjamin Forstner did not produce his improved bit but licensed its manufacture to two Connecticut firms: Colt's Manufacturing Company of Hartford, and the Bridgeport Gun Implement Company. Connecticut Valley Manufacturing picked up the rights in the mid-to-late 1890s as can be evidenced by the exhibition dates on the labels of its boxed sets of Forster's bits. The label seen here references the Chicago World's Fair.

Walter H. Wright

Over time, Alfred M. Wright purchased the shares of the other stockholders and by the late 1890s, the Connecticut Valley Manufacturing Company had become a family business. Wright's younger son, Northam, joined the firm as Secretary and Treasurer in 1895. His timing was grand. Alfred M. Wright had developed an interest in politics, and the change made it easier for him to run for and hold office. The elder Wright joined the Connecticut General Assembly as a member of the Senate in 1897 and served a two-year term. Wright's older son, Walter H., joined the family business in 1899, taking over the treasurer's role. On the death of his father in 1906, Walter H. Wright became the company president.

Walter Wright completed a modest expansion of the works in 1908, adding a single-story addition to the machine shop and a second, two-story structure. Wright must have been mindful of the 1896 fire, though humble in size, the structures were made of brick. The machine shop addition measured 30 x 50 feet and the two-story building 21 x 22 feet.(19)

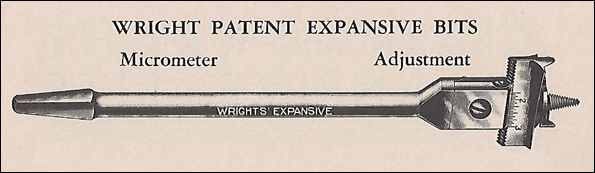

On March 3, 1913, Louis S. Hayden, a machinist at Connecticut Valley Mfg., patented an expansive auger bit with a cross-feed screw that allowed a worker to adjust the diameter of the cutting edge with astonishing precision.(20) Hayden Assigned the patent to his employer. Connecticut Valley produced the design, and in its catalogs, would refer to Hayden's creation as an expansive bit with a "micrometer adjustment." The company manufactured the bit in two sizes, the No. 10 and the No. 20, and sold the tool as the "Wright's Patent Expansive Bit." Each was equipped with two standard cutters. Extra cutters that allowed a user to bore holes up to five inches in diameter were also available. Wright's Patent Expansive Bits sold well and represented one of the few original products the company would produce.

Connecticut Valley Manufacturing Company is a mouthful so it was, perhaps, inevitable the business would come up with a short, easily recognizable trademark. In 1913 it registered its well-known Convalco logo. Though the company would use the logo until its demise, it did not view the Convalco trademark as a substitute for the company name, but rather, as a brand identifier.

Connecticut Valley Manufacturing Company is a mouthful so it was, perhaps, inevitable the business would come up with a short, easily recognizable trademark. In 1913 it registered its well-known Convalco logo. Though the company would use the logo until its demise, it did not view the Convalco trademark as a substitute for the company name, but rather, as a brand identifier.

Like his father, company president Walter H. Wright had an interest in politics. Voters elected him to the Connecticut House of Representatives for the 1905-1906 term and to the Connecticut Senate for a term in 1911. A popular man about town, he was no longer in office on the night of October 17, 1914, when someone planted a bomb under the veranda of his house. Though the blast blew out windows and knocked Wright and his wife out of bed, neither was injured. State Police investigated and found no connection between his service in the legislature and the blast. Labor relations at the plant had been cordial and not considered an issue. Though investigators did not have enough evidence to make an arrest, suspicions centered on a man who had been "occasionally assigned to the Connecticut Hospital for the Insane." A local newspaper reported the unidentified man's insanity was "the result of the intemperate use of alcohol."(21) The case was never solved.

When Walter H. Wright died of "paralytic shock" in 1925, his younger brother, Northam, succeeded him as company president. Northam Wright graduated from Yale Law School and according to his obituary "practiced law for a few years" before becoming head of the business. Like his brother, he shared the family interest in politics and served a two-year term in the Connecticut General Assembly as senator from the 34th district. Little record of his contributions to the company has surfaced. Northam Wright died of a heart attack April 4, 1936.(22)

Third and fourth generations

The death of Northam Wright brought the third generation of the Wright family into the business. Alfred Redfield Wright, the son of Walter H. Wright and nephew of Northam Wright, became company president and would hold the office for twenty years. Citing poor health, he resigned from the company's presidency in 1956 but remained active in the business as chairman of the board. His brother, Martin Walter Wright succeeded him as president, and following family tradition, became chairman of the board on his retirement in 1961.(23) The third generation of the Wright family operated the business during a tough time for independent auger manufacturers, and while there is no evidence of mismanagement on the part of the officers, the company suffered from a lack of vision. Connecticut Valley manufactured a single product—one virtually indistinguishable from its competitors in quality and design. It was perhaps inevitable that without the resources generated by a larger array of products, it lacked the means to aggressively promote its auger bits. The company gradually withered.

The fourth and last generation of Wrights to head the company was Walter Newcomb Wright, the son of Albert Redfield Wright. He headed the company for eight years. On May 6, 1969, he announced the closure of the business. Wright attributed Connecticut Valley's failure to the rising costs of manufacture and an inability to recruit workers (the result of low wages). Thirty employees were let go. Walter Newcomb Wright literally drove a stake into the heart of the company when he pounded the "for sale" sign into the front yard himself.(24)

A second iteration of the company

Another iteration of the Connecticut Valley Manufacturing Company, located in New Britain, was founded April 16, 1981. Its president was Anthony J. Garro, and the company used the traditional Convalco trademark. As of this writing, a line of descent between the original Centerbrook company and Garro's firm has not been established. Garro's business went on to manufacture Forstner bits under the Convalco brand for thirty years. On August 14, 2011, the Morris Wood Tool Company purchased the second Connecticut Valley Mfg. Co. and moved production to its factory in Morristown, Tennessee.

Illustration credits

- Dolan Pond dam: Brush Factory. Center Brook, Conn. [postcard]. Hartford, Connecticut : Chaplin News Company, ca. 1908.

- The Lewis auger bit: Carpentry and Building, December 1883.

- Connecticut Mfg. Company's Dam, Centerbrook Conn. [postcard]. Hartford, Connecticut : Chapin News Company, ca. 1908.

- Portrait of Alfred M. Wright courtesy of Essex Historical Society.

- Connecticut Valley Mfg. wood-frame plant courtesy of Essex Historical Society.

- Connecticut Valley Mfg. brick plant: Main Street, Centerbrook, Conn. [postcard]. New York, New York : The Rotograph Company, ca. 1908.

- Clark's Expansive bit: [Catalog]. A. F. Shapleigh & Cantwell Hardware Company. St. Louis, Mo. : Shapleigh & Cantwell Hardware Company, 1883. p. 70.

- Screw Driver Set No. 12: author's photo.

- Wright's Jennings bits in Bartlett's box: author's photo.

- Connecticut Valley blued bits: author's photo.

- Wright's Jennings bits in Bartlett's box: author's photo.

- Convalco auger bits: author's photo.

- Label for box of Connecticut Valley Improved Forstner bits: author's photo

- Wright Patent Expansive Bit: Connecticut Valley Manufacturing Co. Inc. Wood Boring Tools, Hardware Specialties: Catalog No. 11. Centerbrook, Connecticut : Connecticut Valley Manufacturing, ca. 1939.

- Walter H. Wright: Legislative History and Souvenir of Connecticut. Vol. 8. Hartford, Connecticut : William Harrison Taylor, 1912.

References

- Much of the information on the early years of Essex augermaking is courtesy of: Essex Historical Society and Essex Land Trust. Follow the Falls: Centerbrook. www.essexhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/EHS_014_FTF_centerbrook_web.pdf (viewed 4/13/2022).

- Merwin's Conn. River Business Directory for 1867-68. Hartford, Connecticut, H. Merwin, 1867.

- The countersink: United States Letters Patent No. 60,207; the auger bit: United States Letters Patent No. 90,759.

- United States Letters Patent No. 95,846.

- "Notes & Clippings." Lewisiana, or the Lewis Letter. Vol. 15, No. 9 (March 1905), p. 172.

- Essex Historical Society and Essex Land Trust. Follow the Falls: Centerbrook.

- Connecticut Department of Education. "Ivory and Company Towns." portal.ct.gov/SDE/Publications/Business/Ivory-and-Company-Towns (viewed 8/6/2022).

- History of Middlesex County with Biographical Sketches of Some of Its Most Famous Men. New York : J. B. Beers & Company, 1884. p. 356.

- "$70,000 Fire in Essex." The Journal (Meridan Connecticut) March 2, 1894, p.1

- "Alfred Mortimer Wright." Commemorative Biographical Record of Middlesex County Connecticut. Chicago : J. H. Beers & Co., 1903. p. p. 687-688.

- "Augers and Bits." The Iron Age. (March 16, 1893). p. 635.

- "Court Record: Superior Court-Civil Side-Judge Wheeler." Daily Morning Journal-Courier (New Haven Connecticut). May 2, 1893, p. 4.

- "R. A. Brown & Co.'s Victory." Daily Morning Journal-Courier (New Haven Connecticut). May 18, 1893, p. 4.

- Mironov, Howard. "Clark's Best Quality Screw Drivers." Display at the semi-annual meeting of the Mid-West Tool Collector's Association, Michigan City, Indiana, September 30, 2022.

- [Ad]. The Iron Age, (December 12, 1895). p. 76.

- "Trade Notes." Carpentry and Building, (October 1896), p. xvii.

- United States Letters Patent No. 155,148.

- United States Letters Patent No. 336,709.

- Connecticut. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Twenty-Third Report for the Two Years Ended December 30, 1908. Hartford: State of Connecticut, 1908. p. 37-38.

- United States Letters Patent No. 1,056,670.

- "Bomb Planted in Attempt to Kill Senator Wright." Hartford Courant (Hartford, Conn.) October 18, 1913. p. 19; "Think Insane Man Planted Bomb." Hartford Courant (Hartford, Conn.) October 20, 1913. p. 11.

- "President of Connecticut Valley Manufacturing Company." Hartford Courant (Hartford, Conn.) April 6, 1936. p. 4.

- "Heads Concern." Hartford Courant (Hartford, Conn.) April 5, 1956. p. 7.

- "Essex Company Closes Doors." Hartford Courant (Hartford, Conn.) May 7, 1969. p. 60; Stannard, Charles. "Architects Tell Their Own Story." Hartford Courant (Hartford, Conn.) Feb. 10, 2001. p. 107.