Millers Falls Treadle Tools: Saws, Lathes and Grindstones

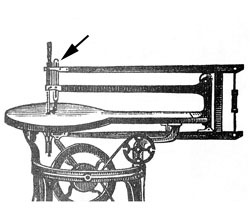

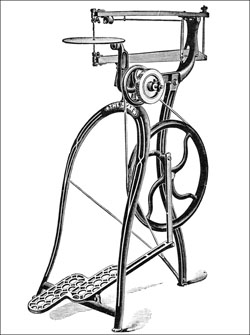

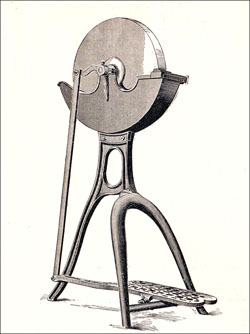

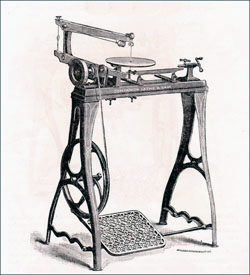

The Carpenters' Scroll Saw (1875-ca. 1884)

The story of the Millers Falls Company's involvement with treadle tools began in 1873 when the firm added hand-held bracket saws to the line. Intended as a fill-in product to keep workers busy during the traditional fall downturn in sales, the saws were popular with hobbyists who made handicrafts and did delicate scroll work during the winter months. Sales exceeded expectation. Between August 1874 and August 1875, the company sold 50,000 bracket saws. The success of its bracket saws provided the inspiration for the development of the firm’s first foot-powered scroll saw. Introduced in 1875, the saw was a serious piece of equipment, weighing in at sixty-six pounds and operating at up to 1,000 strokes per minute. Capable of cutting through stock up to three inches thick, it was equipped with a hard maple table that stood three feet from the ground and blade clamps that could be repositioned to allow a worker to rip a board.(1) With a price tag of $25.00, the tool was no hobbyist's toy. Identified in the catalog simply as Scroll Saw at the time of its introduction, the tool was later given the moniker Carpenters' Scroll Saw to distinguish it from the firm's amateur models.

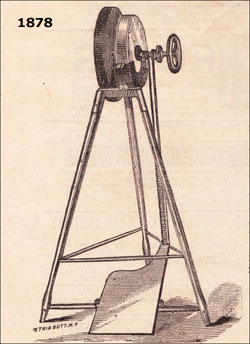

The illustrations of the Carpenter's Scroll Saw found in the company's advertising and catalogs are confusing to say the least. The earliest known image of the saw, found in the December 1875 issue of the magazine Manufacturer and Builder, depicts a saw with a scissor-type arm linkage and lacking a presser foot for holding a piece of stock in place. The 1878 company catalog shows an improved tool with a fixed arm linkage and a presser foot. Apparently, someone at the company mislaid the woodblock for the later version of the saw when the 1881 catalog went to press. The booklet pictures the earlier saw with no presser foot and scissor-type arm linkage, while the accompanying text—identical to that in the 1878 catalog—describes the presser foot. The Carpenters' Scroll Saw, the company's sole attempt to manufacture a professional-grade treadle saw, was not particularly successful and was discontinued by 1884.

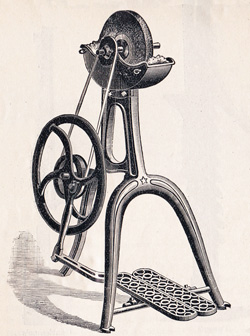

The Lester Saw (1877-1914)

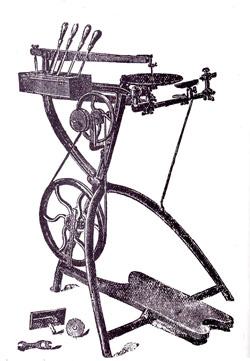

In 1877, the Millers Falls Company introduced the light-weight Lester Saw and sold thousands of the tools within months. Designed by Edward Lester, the plant superintendent, and capable of cutting stock up to an inch thick, the Lester Saw featured a secondary circular saw blade, an emery wheel, a drill chuck and a small lathe, all of which could be mounted to its frame and powered by the treadle. The new scroll saw fit in nicely on the amateur side of the operation's two-pronged approach to the tool business. While its braces, breast drills, vises, levels and chucks were geared to the professional market, the company's Family Tool Chest, push drills, bracket saws, miniature planes and tool handles were targeted to home and family. With the addition of the Lester Saw, the saw blades, small drills, miniature planes, and scroll work patterns ordered by the customers of its bracket saws could be cross-marketed to the purchasers the Lester. When set up so that its lathe and circular saw were operational, the Lester no longer functioned as a scroll saw, although this limitation appeared to have little effect on sales. (The image at left shows an 1877 Lester Saw set up with its lathe and circular saw in their functional positions.)

In 1877, the Millers Falls Company introduced the light-weight Lester Saw and sold thousands of the tools within months. Designed by Edward Lester, the plant superintendent, and capable of cutting stock up to an inch thick, the Lester Saw featured a secondary circular saw blade, an emery wheel, a drill chuck and a small lathe, all of which could be mounted to its frame and powered by the treadle. The new scroll saw fit in nicely on the amateur side of the operation's two-pronged approach to the tool business. While its braces, breast drills, vises, levels and chucks were geared to the professional market, the company's Family Tool Chest, push drills, bracket saws, miniature planes and tool handles were targeted to home and family. With the addition of the Lester Saw, the saw blades, small drills, miniature planes, and scroll work patterns ordered by the customers of its bracket saws could be cross-marketed to the purchasers the Lester. When set up so that its lathe and circular saw were operational, the Lester no longer functioned as a scroll saw, although this limitation appeared to have little effect on sales. (The image at left shows an 1877 Lester Saw set up with its lathe and circular saw in their functional positions.)

Capable of cutting stock of up to an inch thick, the Lester Saw operated at speeds of up to one thousand strokes per minute. Its lathe, which could accommodate a piece of stock nine inches in length, operated at speeds of up to 7,000 revolutions per minute. The standard Lester Saw included a wrench, a screwdriver, four turning chisels, saw blades, and drill points. It sold for $8.00. For another two dollars, a chuck, tail stock and center for working metals was available. A stripped down version of the Lester, which functioned as a scroll saw only, sold for six.

The Millers Falls Company redesigned the Lester Saw in 1878 and referred to the result as the New Lester Saw. The wooden legs of the original Lester were replaced with cast iron; the pitman, emery wheel, and drill chuck were moved to the left of the frame; the lathe to the right. The saw was painted red and green with pin stripe decorations. Other changes allowed the lathe to remain attached to the frame when the saw was in use—a major improvement to the original design. For a time, a cheaper model without nickel-plated components was sold as the Lester No. 2A. A stripped down version of the saw, without the lathe, was available for as long as the tool was offered.

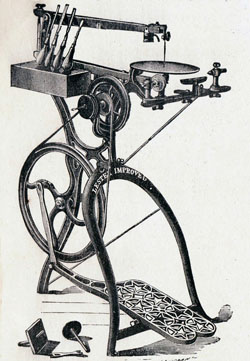

By 1881, the Lester saw had been redesigned again and renamed the Lester Improved Saw. The improved version boasted a sturdier frame than its predecessor. The new frame was effective in reducing the wobble created by the use of the treadle and featured the horseshoe-shaped front legs that defined the appearance of subsequent Millers Falls Company scroll saws. The Lester Improved Saw was now japanned black with red and gilt decorative detailing. Other improvements included a blower to remove dust from the saw table and a cast iron treadle that replaced the wooden version. Shortly afterward, Pratt's Rubber Positive Blower replaced the company's earlier effort. Although the rubber blower was a significant improvement, most of those still extant have deteriorated to the point that they are ineffective.

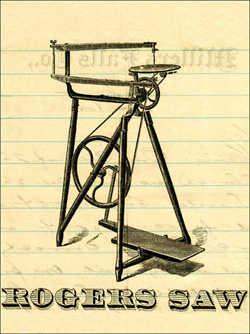

Rogers and New Rogers scroll saws (1878-1925)

The Millers Falls Company brought out its first Rogers treadle saw in 1878. Named after the Secretary of the Board, George E. Rogers, and designed to sell for less than the Lester, the saw had no provision for attaching a lathe or circular saw. Wooden components were painted rather than varnished, and trim was polished or japanned rather than nickel plated. At 1,000 strokes per minute, the Rogers Saw matched the Lester Saw for speed. When set up for sawing, the earliest Lester Saws outweighed the Rogers Saw by ten pounds. The Lester's extra weight gave it the advantage of less wasted energy because its saw operated with less vibration.(2)

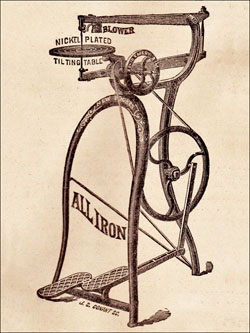

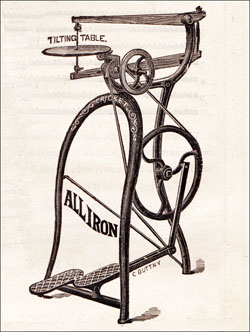

The year after its introduction, the company replaced the Rogers Saw with its New Rogers Saw. The tool was completely re-designed. Its wooden legs were replaced with cast iron, and its arms rode on much improved bearings. Eager to point out the superiority of its metallic support system, illustrations of the saw proudly announced that it was All Iron—conveniently ignoring that fact that its pitman and arms were made of wood. (The pitman would one day become metallic). In 1885, Albert D. Goodell's improved saw clamps were added to the arms. The lever-lock clamps simplified blade installation and significantly reduced breakage.

The company introduced two versions of the New Rogers Saw: the cheaper No. 1 was fitted with a japanned table and an iron balance wheel; the premium No. 2 featured a nickel-plated table and an emery balance wheel that could be used for sharpening. The New Rogers fret saw, with its horseshoe-shaped front legs, became the most widely sold jigsaw of the era. Ornamented with red and gilt trim, selling in the three to four dollar range, and well-made for the price, the New Rogers hit a sweet spot in the market and retained its position as the leading amateur saw for decades.

Cricket Scroll Saw (ca. 1881-1917)

Although the Millers Falls Company advertised the New Rogers as the “best cheap saw in the business,” it went on to develop an even cheaper model, the Cricket Saw. Built with lighter weight castings and not as finely finished, the Cricket weighed eight pounds less than the New Rogers, lacked a dust blower, and sold for two dollars and fifty cents. Weighing in at just seventeen pounds, its arms and pitman were made of second-growth ash rather than the premium ash used on the rest of the company's saws, and while the Cricket sported an iron balance wheel, no emery wheel was included. In most other respects, the saw was similar to the New Rogers.

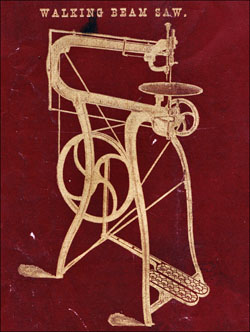

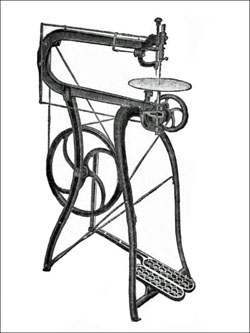

Walking Beam Saw (1884)

The Millers Falls Company's Walking Beam Saw first appeared on the back cover of its 1884 catalog. (A walking beam saw is a jig saw whose arms remain parallel during operation.) The back cover noted:

To do accurate work a saw must run in guides. Hitherto, all saws made on that plan were lifted with a spring; as this spring was not positive in its action, resort was had to movable arms and the guides were dispensed with. We have now overcome the long-felt difficulty by using the walking-beam motion. By this arrangement we are able to make a saw better than the best and almost as cheap as the cheapest.

It has a solid iron frame, but no wooden arms, as the saw runs in guides, upright. Drilling Attachment of the most approved pattern, one of our new Cyclone Blowers made of pure rubber, latest improved clamps, and very heavy Nickel-Plated Tilting Table. The Balance Wheels are large and drive the machine with great power and steadiness. The iron frame is japanned and striped with gold, while all working parts are made of steel. We see no reason why this saw will not take the place of all higher price machines.

While the company saw no reason that the saw would not take the place of all higher price machines, it didn't. The Millers Falls Walking Beam Saw was out of production by the time the 1885 catalog was published.

No. 387 Star Scroll Saw (1899-1925)

The company introduced the Star Saw to meet the demand for an amateur machine more substantial than the New Rogers. The saw's arms were centered, rather than attached to the side of their support casting, providing for more efficient movement. The upper arm rode atop the frame, and the back of the lower arm passed through an opening in the frame assembly. The arrangement allowed the arms to remain parallel during operation, creating an efficient walking beam motion. The 1905 catalog noted:

To adjust the Arms all that is necessary is to loosen the Bolt which goes through the Upper Arm in front of casting, and crowd the Arm sideways either to right or left, and into line with the lower one; the hole in casting is elongated to permit change of position as described.

The drive wheel on the Star Saw was heavier than that of the New Rogers with the extra weight providing additional power for sawing thicker stock. The Star came with two balance wheels, one of iron and one of emery, providing for a steadier operation. The emery wheel was attached to its axle with adjustable clamps which allowed for easy substitution of a buffing attachment, small sandstone wheels or other grades of emery. Like the New Rogers, Lester, and Cricket Saws, the Star Saw was equipped with a tilting saw table.

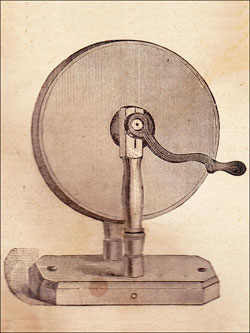

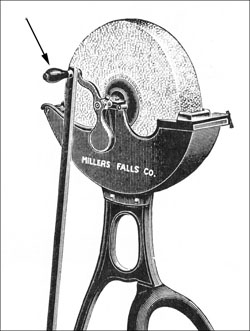

Family Grind Stone (ca. 1878-1894)

This early image of the Millers Falls Family Grindstone is appears on Page 16 of the February 1879 issue of Scribner's Monthly. The accompanying text notes:

This early image of the Millers Falls Family Grindstone is appears on Page 16 of the February 1879 issue of Scribner's Monthly. The accompanying text notes:

Inventors have taxed their ingenuity for many years in getting up household tools and utensils, the thing most needed has been the longest delayed, that is a good Family Grindstone. It runs with foot power, and it is operated by a clutch so that whenever the foot touches the treadle it starts off in the right direction, and will run at fast or slow speed as desired. The stone is 8 inches in diameter 1 1/2 inches thick, and made at the Huron quarries expressly for this use.

The Emery Wheel is 10 inches in diameter and 1 inch thick. It is double coated with best Wellington Mills Emery, and will last for years; when not in use it is taken off by loosening a thumb-screw, and laid aside.

The trough for the stone has an enlarged pocket for holding a sponge, which prevents it from throwing the water when running at a high rate of speed. For grinding carving knives and all light tools, and for polishing cutlery, this machine is perfect.

It weighs 26 pounds and is taken down and boxed for shipping. Price including box, $3.00. We will ship it for any part of the county on receipt of the price. For sale by all Hardware dealers.

The company made much of the sourcing of its abrasives, and given what was available at the time, they were first rate. Emery is a naturally occurring hard, dark rock composed of aluminum oxide. The quality of the stone can vary widely, and the Wellington Mills operation, based in London, England, had access to the best of the mineral through its sources in Asia Minor. Wellington Mills, which also manufactured sandpaper, won the highest award medal in its category at Centennial International Exhibition at Philadelphia Exhibition in 1876—a fact not likely to have escaped the attention of Millers Falls Company executives. The Huron quarries, the source of the Millers Falls Company's sandstone wheels, were located in Michigan along Lake Huron. Soft and wet when freshly mined, Huron sandstone cured as it dried and was noted for its hardness, fineness and lack of impurities. The Huron product was widely considered to be superior to the Ohio sandstone mined at Berea and Marietta which was softer and best suited to coarse work.

The company made much of the sourcing of its abrasives, and given what was available at the time, they were first rate. Emery is a naturally occurring hard, dark rock composed of aluminum oxide. The quality of the stone can vary widely, and the Wellington Mills operation, based in London, England, had access to the best of the mineral through its sources in Asia Minor. Wellington Mills, which also manufactured sandpaper, won the highest award medal in its category at Centennial International Exhibition at Philadelphia Exhibition in 1876—a fact not likely to have escaped the attention of Millers Falls Company executives. The Huron quarries, the source of the Millers Falls Company's sandstone wheels, were located in Michigan along Lake Huron. Soft and wet when freshly mined, Huron sandstone cured as it dried and was noted for its hardness, fineness and lack of impurities. The Huron product was widely considered to be superior to the Ohio sandstone mined at Berea and Marietta which was softer and best suited to coarse work.

By 1881, the Millers Falls Company had redesigned the Family Grind Stone. Reading between the lines, text seen in that year's catalog suggests that there may have been complaints about the quality of the first version of the grindstone:

After much experimenting we have now fully perfected our Grind-Stone for family use and offer it to the public with a FULL GUARANTEE that it is a perfect machine; and also that it will please everyone who buys it.

The attachments for the machine's legs and the drive assembly were beefed up, bracing for the lower legs was re-designed, and the emery and sandstone wheels were now the same size—ten inches in diameter and one inch thick. In the early 1890s, the company changed the size of the emery wheel yet again, shrinking it to four inches in diameter and 3/4 of an inch thick. One can only assume that the price of emery had risen substantially. The wood-framed Family Grind Stone was out of production by 1894.

Hand-Power Family Grind Stone (ca. 1881-ca. 1884)

Not all of the company's grindstones were designed to be foot-powered. The 1881 catalog pictured a hand-cranked stone mounted on a wooden frame. The hand-crank model was available in three sizes, with stones measuring eight, ten, and twelve inches in diameter and varying between 1 1/4 inches and 1 1/2 inches thick. Although the catalog description of the Hand Power Family Grind Stone was minimal in the extreme, it would be safe to conclude that most readers pictured a well-behaved son or daughter powering the device while Papa did the sharpening.

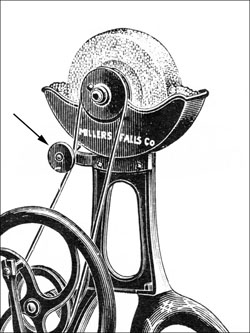

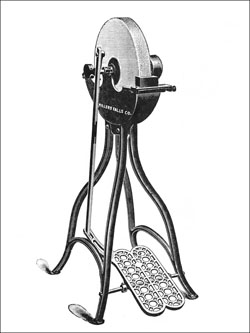

Family Grindstone No. 2 (1894-1922)

The Millers Falls Company replaced its wooden frame Family Grind Stone with the iron-framed Family Grindstone No. 2 about 1894. The machine featured a large, belt-driven drive wheel and represented a major advance in both construction and efficiency over its predecessor. Unlike the earlier Family Grind Stone, the No. 2 was a one-stone machine. Its single grinding wheel was manufactured of Huron-quarried sandstone measuring eight inches in diameter and 3/4 of an inch thick. By 1901, the company had added an adjustment wheel to take up slack in the belt. The addition was likely a response to the unforeseen problem of belts stretching due to the inertia encountered in trying to put a sandstone wheel into motion.

Family Grindstone No. 3 (1897-1922)

The Family Grindstone No. 3 first appeared in the 1897 catalog. Of the same general quality as the Family Grindstone No. 2, it came equipped with a fourteen-inch sandstone wheel that was 1 3/4 inches thick. The weight the wheel, however, necessitated a design alteration. Instead of a belt assembly, power was transmitted from the treadle to the wheel by means of a wooden pitman. The change eliminated the need for periodic adjustments to take up slack in the belt. Between 1901 and 1904, the company added a hand crank to the No. 3 grindstone. Although the No. 3 remained a foot-powered machine, the crank added the option of turning the wheel by hand. The crank was weighted on the end opposite its handle, providing a counterweight that steadied the motion of the wheel and helped to maintain the stone's velocity.

Family Grindstone No. 4 (1905-1922)

The Millers Falls Company introduced the Family Grindstone No. 4 as a deluxe version of its Grindstone No. 3. The four-legged frame of Grindstone No. 4 provided a degree of stability not found on the No. 3. The No. 4 lacked the hand crank typical of the later versions of No. 3 and featured a four by two-inch pulley that allowed for the use of a power drive. Today, anyone attempting to connect a No. 4 power drive to a high-speed motor should be forewarned that a century-old sandstone wheel is likely to explode into fragments when subjected to this sort of abuse. The use of the foot-powered treadle is far safer.

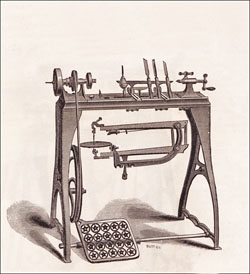

Goodell Lathe (1885-1922)

The Millers Falls Company introduced the Goodell Lathe in 1885 as it expanded its efforts to reach the amateur market. Named after the plant superintendent, Albert D. Goodell, the lathe featured a bed just twenty-four inches long and capable of accommodating a fifteen and one-half inch piece of stock. Although the small size of the lathe limited its use to the turning of novelty items, its optional sawing attachment allowed a user to do scroll saw work without having to purchase a second machine. While not particularly efficient, the combination of the two tools allowed for the creative construction of book ends, corner shelves, letter holders and the like. The lathe's drive wheel was designed with two grooves of different depths on its face, a feature that allowed the belt to be repositioned in order to effect a change of turning speed.

The basic Goodell sold for ten dollars and included an emery wheel, a spindle with a small chuck for holding drill points, a larger chuck for 1/4 inch twist drills, and long and short tool rests. Five turning chisels, a drill chuck, a wrench and a set of drill points were included as well. For an additional two dollars, the detachable scroll saw head could be added to the outfit. (Mounting the saw head required just one bolt.) An optional small circular saw attachment became available about 1890. The cost of a complete Goodell unit—a lathe with detachable saw—was roughly comparable to that of the company’s Lester unit—a saw with detachable lathe. While the Lester had the advantage of being able to cut stock two inches thick, its lathe attachment was limited to stock nine inches in length.

At the time that he was involved in designing his lathe, Albert D. Goodell came up with an improved method for attaching scroll saw blades to the arms of its scroll saw head. His improved clamps served not only to hold the blade in place, but also to draw it taut. Well-designed and easy to use, Goodell's clamps were used on the saw attachments for the Goodell and Companion lathes and on the New Rogers and Cricket scroll saws. Albert Goodell was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 332,391 for his clamping invention.

Companion Lathe (1885-1922)

The Millers Falls Company made its appeal to the home hobbyist in a fairly sophisticated way when it developed the Companion, a combination treadle lathe and saw designed exclusively for the youth market. The Companion units were designed in consultation with Perry Mason & Co., the publisher of The Youth’s Companion, a magazine sometimes credited with the popularization of scroll sawing among the younger set. Named after the magazine, the Companion cost $1.50 less than the Goodell model and was heavily promoted in the publication. Perry Mason & Company built The Youth's Companion's reader base by using prizes to encourage young people to sell subscriptions. Companion Lathe outfits were among the premiums awarded to those young entrepreneurs adept at doing so. An issue of the magazine published in 1885 provided this description for would-be salesmen:

The Companion Lathe and Saw is the best combination Lathe and Jig Saw now made. It combines the most valuable qualities and improvements of all our former styles. The superior points of this machine are found in the following reasons: 1, Strong and heavy castings and extra finish. 2, Large treadle. 3, Automatic Dust Blower. 4, Anti-friction Blade Wheel. 5, Large Emery Wheel. 6, Rigid Head and Tail Stocks. 7, Improved Saw Clamps. 8, New Straining Rod. 9, High Speed.

The Lathe will turn a piece of wood 16 in. in length. There is no machine of the kind now selling for $12 which is a practical and good as this one. We send with each machine 3 Turning Tools, Screw Driver, Belt hooks, Direction Sheet, Wrench, 24 Griffen Patent saw Blades, 6 Drill Points, 71 Designs ...

Given for nine new names, or for six new names and $1.40 additional. or three new names and $2.00 additional. Price of machines $8.00 complete.(3)

The Companion Lathe was virtually identical to the Goodell Lathe but was not so well-finished and came with fewer tools. The Millers Falls Company's lightweight lathes got little respect from professional woodworkers and, indeed, were seen by one contemporary writer as fit only to “sell to boys and ministers of the gospel."(4)

No. 417 Lathe (1915-1922)

In 1915, the Millers Falls Company introduced a foot-powered lathe for workshops where electricity or other forms of power were lacking. Weighing 175 pounds and capable of accommodating a forty-inch piece of stock, the machine was equipped with a heavy two-speed drive wheel that required the use of a one-inch belt. Not intended for the hobbyist market, the No. 417 lathe did not feature a scroll saw, tiny drill-point spindle or grindstone attachment. It was shipped without turning tools, and there was no option for attaching a gimmicky circular saw. Although the company advertised that the lathe was intended for "woodworking and light metals," an examination of its overall design suggests that few, if any, were used for this latter purpose. The No. 417, along with the rest of the company's foot-powered tools, was dropped from the line about 1922.

Illustration credits

- 1875 Carpenters' Scroll Saw: This scan of the 1875 version of the saw is from the outdated block used to print the 1881 version of the company's catalog. Catalogue 1881. New York: Millers Falls Company, 1881.

- 1878 Carpenter's Scroll Saw: Millers Falls Co., Millers Falls, Mass. New York: Millers Falls Company, 1878.

- Lester Saw images: The Lester Combination Scroll Saw Manufactured by the Millers Falls Company. New York: Millers Falls Company, ca. 1877; Millers Falls Co., Millers Falls, Mass. New York: Millers Falls Company, 1878; Catalogue 1881. New York: Millers Falls Company, 1881.

- Rogers Saw: Letter, Edward P. Stoughton to Millers Falls Company, Millers Falls, Massachusetts, 20 November 1878. (Verso of stationary)

- New Rogers Saw: Catalogue 1881. New York: Millers Falls Company, 1881.

- Cricket Saw: Catalogue no. 24. New York : Millers Falls Company, 1894.

- Walking Beam Saw: Catalogue 1884. New York: Millers Falls Company, 1884; Amateur Work Illustrated. v.5, (1885).

- Star Scroll Saw: Catalogue No. 35. Millers Falls, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1915.

- 1878 Family Grindstone: Scribner's Monthly, (February 1879).

- 1881 Family Grindstone: Catalogue 1881. New York: Millers Falls Company, 1881.

- Hand-Power Family Grindstone: Catalogue 1881. New York: Millers Falls Company, 1881.

- Family Grindstone No. 2: Catalogue No. 24. New York : Millers Falls Company, [no date, but 1894].

- Family Grindstone No. 2 adjustment wheel: Catalogue No. 35. Millers Falls, Mass. : Millers Falls Co., November 15, 1915.

- Family Grindstone No. 3: Catalogue No. 25. New York : Millers Falls Company, [no date, but 1897].

- Family Grindstone No. 3 hand crank: Catalogue No. 35. Millers Falls, Mass. : Millers Falls Co., November 15, 1915.

- Family Grindstone No. 4: Catalogue No. 35. Millers Falls, Mass. : Millers Falls Co., November 15, 1915.

- Goodell Lathe: 1886 Catalogue: Millers Falls Company, Hardware Manufacturers. New York : Millers Falls Company, 1886.

- Goodell Saw Blade CLamp: United States Letters Patent No. 332,391.

- Companion Lathe: 1886 Catalogue: Millers Falls Company, Hardware Manufacturers. New York : Millers Falls Company, 1886.

- No. 417 Lathe: Catalogue No. 35. Millers Falls, Mass. : Millers Falls Co., November 15, 1915.

-

References

- The information of three-inch stock: "Scroll-Saw." Manufacturer and Builder. v. 7, no.12, (December 1875). p. 289.

- Millers Falls Company. Millers Falls Company, Millers Falls, Mass.: Manufacturers of Hardware and Mechanics' Tools, Including Tools for Bracket Sawing and Carving. New York, N. Y. ; Boston, Mass. : Millers Falls Company, [ca. 1878]. (A small leaflet)

- The Youth's Companion. v. 58 (1885), p. 435.

- Wood Workers' Tools: Being a Catalogue of Tools, Supplies, Machinery and Similar Goods Used by Carpenters, Builders, Cabinet Makers, Pattern Makers, Millwrights, Carvers, Ship Carpenters, Inventors, Draughtsmen, and all "Wood Butchers" not Included in the Foregoing Classification, and in Manufactories, Mills, Mines, etc. etc. Detroit, Michigan : Charles A. Strelinger & Company, 1897, p. 862.