Langdon Mitre Box & the Rogers Family, 1875-1906

Relocating to Millers Falls

Two weeks after the creditors of the Northampton-based Langdon Mitre Box Company met to discuss its bankruptcy, notice appeared in the February 22, 1875, Greenfield Gazette & Courier that Deacon David C. Rogers had contracted for water power with the Millers Falls Company and was about to begin the manufacture of miter boxes. The miter box operation was to be housed in the Millers Falls factory, a logical location in that the larger company was sales agent for much of its production. Deacon Rogers' Langdon Mitre Box Company moved into a part of the plant that had been vacated by the Chapman Cutlery Company. The cutlery company, established by Frank R. Chapman, specialized in steel-handled table knives and, with an 1800 pound drop forge, was capable of turning outs as many as fifty dozen utensils in a day. Despite a recessionary economy, Chapman Cutlery was holding its own. Its departure from the Millers Falls complex was the result of a decision to relocate, rather than a bankruptcy.(1)

Two weeks after the creditors of the Northampton-based Langdon Mitre Box Company met to discuss its bankruptcy, notice appeared in the February 22, 1875, Greenfield Gazette & Courier that Deacon David C. Rogers had contracted for water power with the Millers Falls Company and was about to begin the manufacture of miter boxes. The miter box operation was to be housed in the Millers Falls factory, a logical location in that the larger company was sales agent for much of its production. Deacon Rogers' Langdon Mitre Box Company moved into a part of the plant that had been vacated by the Chapman Cutlery Company. The cutlery company, established by Frank R. Chapman, specialized in steel-handled table knives and, with an 1800 pound drop forge, was capable of turning outs as many as fifty dozen utensils in a day. Despite a recessionary economy, Chapman Cutlery was holding its own. Its departure from the Millers Falls complex was the result of a decision to relocate, rather than a bankruptcy.(1)

When the production of Langdon miter boxes moved to the Millers Falls factory, the D. C. Rogers family, the owners of the company, took up residence in the nearby, but larger city of Greenfield. The Rogers’ son, George Edwin Rogers, and his wife, the former Clara Clark, relocated to Greenfield as well. Though the timing of the younger couple's arrival is not apparent, by July 1875 the younger Rogers were well enough established to contemplate a trip to Martha’s Vineyard with Levi J. Gunn, the treasurer of the Millers Falls Company.(2) The men would become business associates several years later when George E. Rogers became the Secretary of the Board of the Millers Falls Company. Since the holder of such a position typically held a substantial financial position in the business, there is no reason to doubt that between them, the two Rogers families had made a sizable investment in the larger enterprise. Though housed in the Millers falls plant, the Langdon Mitre Box Company would remain an independent entity until 1906.

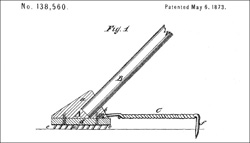

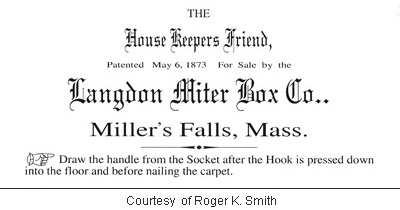

In addition to selling its miter boxes, the Langdon operation marketed at least two other tools during its early years in Millers Falls. One, the Housekeepers Friend, was a carpet-stretcher patented May 6, 1873, by Joseph S. Greene and Thomas D. Bradt of Watertown, New York. The device was equipped with a wide head containing numerous teeth which, when engaged in the carpet, distributed the pressure exerted by the operator, avoiding tears and strains to the backing. The device was not so kind to floors; its anchoring prong dug a significant pit in the wood each time pressure was applied. Sadly, the only evidence for the Langdon's operation's sale of the tool is a photocopied fragment of a page from an unidentified periodical. The tool does not appear in any of the Langdon Mitre Box or Millers Falls Company price lists that have surfaced to date.(3)

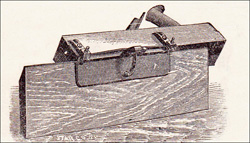

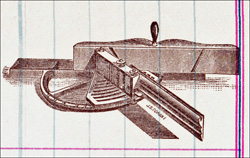

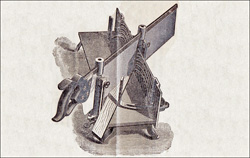

Another of the tools that Langdon began to sell early on was an adjustable jointer gauge invented by Levi A. Alexander, a resident of Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Jointer gauges are handy tools designed to assist woodworkers in controlling the angle at which the sole of a plane meets a piece of stock—thereby facilitating the creation of a uniform square or bevel over the entire length of the board. Designed to be fitted to a wood-bodied bench plane, Alexander's Jointer Gauge was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 129,508 issued on July 16, 1872. Manufactured by Langdon Mitre Box, the Alexander gauge appeared in the company's catalogs and price lists for nearly thirty years. Though the growing popularity of iron planes eventually doomed the tool, the company continued to carry Alexander's tool until relatively late in the game. It was not replaced by a model suitable for use on a metal-bodied plane until 1904, when Langdon introduced the Perfection Jointer Gauge.

Another of the tools that Langdon began to sell early on was an adjustable jointer gauge invented by Levi A. Alexander, a resident of Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Jointer gauges are handy tools designed to assist woodworkers in controlling the angle at which the sole of a plane meets a piece of stock—thereby facilitating the creation of a uniform square or bevel over the entire length of the board. Designed to be fitted to a wood-bodied bench plane, Alexander's Jointer Gauge was awarded United States Letters Patent No. 129,508 issued on July 16, 1872. Manufactured by Langdon Mitre Box, the Alexander gauge appeared in the company's catalogs and price lists for nearly thirty years. Though the growing popularity of iron planes eventually doomed the tool, the company continued to carry Alexander's tool until relatively late in the game. It was not replaced by a model suitable for use on a metal-bodied plane until 1904, when Langdon introduced the Perfection Jointer Gauge.

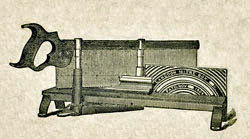

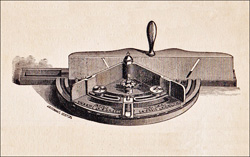

The Perfection gauge was designed to be attached to the side edge of a plane by the rotation of two eccentric cams that pinched its shoulder against a pair of L-shaped arms. One of the greatest strengths of the Perfection design was the speed and ease with which the gauge could be attached to, or removed from, a plane. Langdon did not have to forego sales to those woodworkers clinging fiercely to their wood-bodied planes, the bolts attaching the cams to their arms could be removed and wood screws passed through the holes—a modification that allowed for its use on the older-style tools. Manufacture of the Perfection Jointer Gauge eventually passed on to the Millers Falls Company who renamed it the No. 88. It remained in production until 1944.

Rogers & Spurr Manufacturing Company

In February 1879, David C. and George Rogers applied to the United States Patent Office to register a trademark consisting of the words “Rogers & Son” and a feathered arrow. The application indicated that the men, principals in a Greenfield business named Rogers & Son, intended to go into the business of manufacturing table knives, forks, spoons and the like. They produced no tableware, but the following year, they agreed to allow George W. and Lorenzo Spurr, of George W. Spurr & Company, to use their trade mark on silver-plated dinnerware for a royalty of five cents per dozen pieces. The original arrangement lasted five months—until February 1881—when David C. Rogers, George E. Rogers, Henry L. Pratt (president of the Millers Falls Company) and George W. Spurr formed the Rogers & Spurr Manufacturing Company, an entity that agreed to pay the Rogers a royalty of four cents per dozen on 25,000 pieces of tableware.

The arrangement with Spurr was an attempt to capitalize on the Rogers family name by linking it to several firms noted for the quality of their silver plate. The reputation of “Rogers” silver rested on the reliability of the products manufactured by the brothers Rogers, siblings whose various Connecticut-based businesses were pioneers in the production electro-plated table settings. The original Rogers families had trademarked three names that were in active use at the time that Rogers & Spurr went into business—Rogers & Bro., Rogers Bros. and Wm. Rogers & Son.

The William Rogers Manufacturing Company promptly brought suit against Rogers & Spurr.(4) The action took place so quickly that Spurr was forced to condition the new company’s payment of royalties to George and D. C. Rogers on the favorable settlement of the case. The trademarks were very close—William Rogers & Son (with a small anchor) and the newcomers' Rogers & Son (with a small arrow). The plaintiffs were not kind in their description of Rogers & Spurr Manufacturing, accusing them of making and selling “inferior goods” and of adopting a deceptive trademark in order to deceive purchasers. Judge C. J. Lowell of the United States Circuit Court for the District of Massachusetts agreed with the complainants:

This royalty is paid for a falsehood. The name of these Rogerses is not of the slightest value in the silver plating business, which they never learned or practiced; nor were they ever partners, as I read in evidence, except in hiring out this trademark. It is impossible that this royalty can be paid for anything but the chance of purchasers supposing it to represent some other Rogerses.(5)

The Rogers name does not express a certain sort of goods but serves as a warranty of good workmanship, because all those who have used it have followed faithfully the excellent example of the original Rogerses, who insisted on honest work.(6)

Lowell considered that the case was not about the simple right of a person to use his or her name for a business but about deceptively appropriating the goodwill (reputation) of a business holding a valid trademark. The case, William Rogers Manufacturing Company vs. Rogers & Spurr Manufacturing Company, was decided on April 22, 1882. It is frequently cited in legal treatises dealing with the right of an individual to use a family name for business purposes.

New miter products

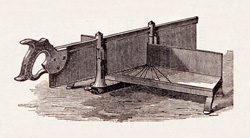

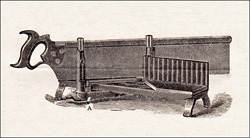

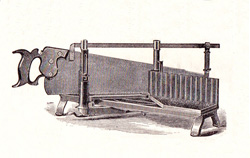

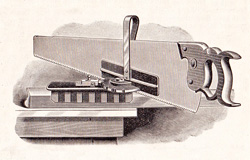

Between late 1879 and early 1883, the Langdon Mitre Box Company introduced a series of tools that would define its product line for the next two decades. On October 21st, 1879, the Patent Office issued United States Letters Patent No. 220,732 to David C. Rogers and Albert D. Goodell, a master mechanic soon to become superintendent of the Millers Falls Company. Patent documents described their invention as "an improvement in miter-boxes" and indicate that they signed their rights to the design over to the Langdon Mitre Box Company. The first Langdon boxes had been designed with a set number of saw stops—limiting its adjustment to a series of predetermined angles. The improved design, while still equipped with the convenient stops, allowed its saw to be locked into position at any point between ninety and forty-five degrees. The Langdon company marketed the invention as the New Langdon Miter Box, and it remained in production, first by Langdon and then by the Millers Falls Company, until the early 1930s.

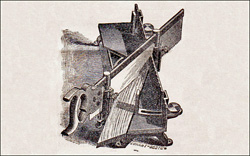

On September 19, 1882, David C. Rogers was issued United States Letters Patent No. 264,766 for what was to become known as the Rogers Miter Planer. The tool depicted in the patent drawings is fairly close to the tool as manufactured, but it is apparent that the design had passed through a number of revisions before being brought to its final state. Langdon Mitre Box Company bill heads from the early 1880s depict a tool that is obviously a developmental model and is simply labeled Adjustable Miter Planer. The Rogers miter planer, a deluxe shoot board with a semi-circular frame, was capable of delivering an almost flawless trim of angle cuts on mating pieces of stock. The tool, which cut on both the push and pull strokes, would soon become a favorite of picture framers who valued its versatility, accuracy and economy of motion. The miter planer was capable more sophisticated work; two adjustable, lockable guides on its rotating bed plate provided rests which allowed for the precision trimming of the wedge-shaped pieces used to fabricate cylindrical and oval-shaped forms in patternmaker’s shops. The Rogers miter planer was popular enough to remain in the Millers Falls Company catalog for over forty years.

Five months later, the Patent Office issued patent no. 272,903 to D.C. Rogers for a tool that would be marketed as the New Langdon Improved Miter Box. The improved New Langdon featured an adjustable arm which allowed the sawyer to reposition a piece of stock to effect a cut at any angle between ninety and seventy-three degrees. The relatively narrow bed of the New Langdon Improved Miter Box served as a practical limitation on the angle of cut. The company soon introduced a version with a wider bed that would make a cut at any angle between ninety and eighty-eight degrees. Interestingly, the wider version of the New Langdon Improved was given a shortened moniker. The "New" was dropped from its name, and it was simply sold as the Langdon Improved Miter Box. The decorative backstop of the Langdon Improved, with its triple arcs and prominent patent dates, was a throwback to the decorative design that graced the Company's first miter boxes. As was the case with the earlier miter boxes. The artwork depicting the tool remained in use long after the cast design was eliminated. Although the need for the capability to cut such extreme angles would appear to have been limited, demand was such that the New Langdon Improved and Langdon Improved were to appear in Millers Falls Company catalogs for over four decades.

A family's business

The Langdon Mitre Box Company published small multi-fold price lists that were enclosed in envelopes marked Preserve This and shipped along with its miter boxes. The covers of the price lists typically included names of the company officers. The January 1881 price list identifies Geo. E. Rogers and A. F. Rogers as the operation's proprietors. The name David C. Rogers, the patriarch who brought the business to Millers Falls and patented the Rogers Miter Planer, is nowhere to be seen. D. C. Rogers' absence from the proprietor listing minimizes his actual role in the operation—Geo. E. Rogers was his son, and A. F. Rogers, Amelia Foote Rogers, his wife. It may be that his low profile was the result of concern about the lawsuit pending against him for trading on the reputation of William Rogers sliver plate. The 1887 price list, coming out five years after the lawsuit, lists George Rogers as company president and his father D.C. as serving in the treasurer's position. The death of D. C. Rogers in 1889, at age seventy-five, necessitated yet another change in the officers of the Langdon Mitre Box Company. George E. Rogers became company treasurer, and C. C. Rogers (his wife, Clara Clark Rogers) became company president. By this time, Amelia Foote Rogers no longer had a role in the company. She died in 1896.

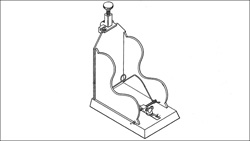

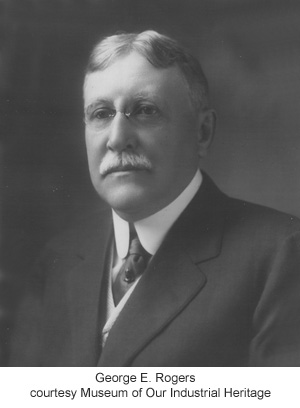

George Rogers was more business man than tool developer. While David Childs Rogers had taken an hands-on interest in the tools developed for the Langdon Mitre Box Company, his son was not so actively engaged. Although Millers Falls Company lore has it that the New Rogers treadle saw was named for its secretary, George Rogers, there is no evidence that he played a role in its development. That said, the younger Rogers was occasionally involved in the patent process. In 1876, he collaborated with Albert D. Goodell to develop a specialized holder for filing postal cards in alphabetic order. (At the time, postcards were becoming a widely accepted method of inter-business communication.)(7) Basically a cut-away box with a mouse-trap spring to hold the cards in place, no evidence of its manufacture has been found. The patent was assigned to George Rogers rather than to the Millers Falls or Langdon Mitre Box Company.

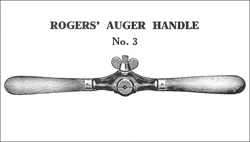

When George Rogers was issued his second patent on October 11, 1892, for a T-auger handle capable of accepting a variety of square-shanked bits, it was assigned to the Millers Falls Company.(8) The design was basic; two malleable iron pieces in the center of the handle formed a clamp that could be adjusted by means of a a pair of thumbscrews. By the time that the clamp was introduced to the Millers Falls lineup, it had been modified so that it featured a single thumb screw. Compact, fairly light weight, easy to adjust and easy to manufacture, the Rogers' Auger Handle was a successful addition of the Millers Falls Company's catalog. In 1910, a second version of the auger handle—featuring a longer clamp adjustable by two thumbscrews—appeared in the catalog. This later iteration of the handle is virtually identical to the tool depicted in the 1892 patent drawings. The wooden outer arms of both tools were manufactured from turned ash.

Rogers, Lunt & Bowlen

In 1890, the cutlery and silverware manufacturer A. F. Towle & Son Company moved to Greenfield. Established in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1880, George E. Rogers and local businessman Richard N. Oakman were major stockholders in the operation and influential in the decision to relocate. The Greenfield businessmen's association raised $10,000 to build a factory for the business, and things went well for the enterprise until the economic downturn of 1893. Oakman, who was serving as company president, became concerned and sought to diversify the product line by subcontracting to produce parts for such bicycle companies as Victor and American Sword in Chicopee, Massachusetts, and the Schwinn Company of Chicago. While visiting Chicago, he saw a horseless carriage and became obsessed with the idea of manufacturing automobiles. He founded the Oakman Motor Vehicle Company, and by late 1897, a prototype was under development in a shed behind behind the Towle & Son factory. Oakman began transferring money out of the cutlery and silverware operation to fund his pet project and managed to produce some fifty vehicles before concerned bankers foreclosed on the tableware business in 1900.(9)

When the assets of A. F. Towle & Son were sold to a group organized by George C. Lunt, Towle's manager of operations, George E. Rogers came on board as a major investor. Joining the men was W. C. Bowlen, a former engraver with Towle, and in 1902, the enterprise was incorporated as the Rogers, Lunt & Bowlen Company. As was the case when the Rogers family and Lorenzo Spurr tried to market under the Rogers name some twenty years earlier, one of the original Rogers silver plate companies brought suit over the enterprise's use of the Rogers name. This time, however, the use of the name was not enjoined, and by 1909, George Rogers was serving as company president. The new silverware business was a success and would produce high quality tableware for over a century. Renamed Lunt Silversmiths in 1935, the operation become the official supplier of tableware to the United States foreign service. Its Embassy Scroll pattern earned a place as the standard table service for U.S. embassies and consulates throughout the world.

More miter boxes

Albert D. Goodell, the Millers Falls Company employee who designed the New Langdon Miter box for the Rogers family in 1879, sold a second miter box design to George Rogers in 1895. By this time, Goodell had left Millers Falls and was operating a small manufactory in Shelburne Falls with his son Frederick, producing such items as bit braces, chucks and butt gages. Goodell's new design, United States Letters Patent No. 544,092, was for a miter box with a large lever that allowed for one-handed raising and lowering of the saw and controlling the depth of cut. A handy feature, as anyone who has used a traditional miter box can attest, there is no documentary evidence to suggest that the Langdon Mitre Box Company put Goodell's lever idea into production. Langdon's reluctance to incur the expense of updating its electrotypes when its products were modified presents presents a considerable impediment to understanding the extent to which the Goodell patent influenced production. The patent did, however, include a latch bar that allowed a user to suspend the saw over a piece of stock while it was being positioned. A modified version of the latch bar would appear with the introduction of the the Langdon Acme miter box in 1904.

William J. Parsons, a Millers Falls Company employee and nephew of George Rogers, broke with tradition when he patented a light-weight miter machine in 1902. He assigned the rights to his invention to the Langdon Mitre Box Company.(10) Although the company would market his invention as the Star Miter Box, the individuals who prepared the patent papers for his invention were apparently unsure of just how to describe it. The term miter box originally referred to the homemade, three-sided wooden boxes with pre-sawn slots that generations of woodworkers used to improve the speed and accuracy of their angled cuts. Though the term was adopted for the table-type devices that became popular in the latter half of the nineteenth century, Parsons' new invention was anything but box-like, so so it may have seemed that the term miter machine was a better description. The smaller size and durability of the Star Miter Box made it especially useful in situations where heavy table-type miter boxes with their fragile cast iron legs were a liability. Langdon would promote the portability of the Star by pointing to its utility for such uses as making cuts in cornice molding while standing atop a ladder. When the Millers Falls Company acquired the Langdon Mitre Box Company, it brought out a re-designed version of the Star that featured a tilting saw guide—a modification that allowed the user to make compound miters. The new version appeared in the catalog alongside Parsons' original design.

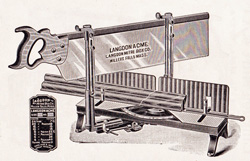

W. J. Parsons followed up his work on the Star Miter Box with an even greater success—the Langdon Acme Miter Box. Though there was nothing revolutionary in its design, those who prepared the patent papers for the full-featured Acme box found enough differences in its swing bar and saw guides to claim seven points of uniqueness.(11) Among the changes was Parsons' re-design of Albert D. Goodell's 1895 latch bar, the feature that allowed a workman to suspend a saw over a work piece while last minute adjustments were being made. The re-design divided Goodell's bar into two independent locks and was close enough to the original that Goodell's design was referenced in the patent application. Since the patent for the Acme Miter box was not issued until almost three years after the appearance of first models, the earliest Acme boxes referenced only Goodell's patent on the brass plate attached to the box. Mention of Parsons' patent did not appear until 1907. With extra long saw guides, the ability to lock the saw well above the work piece, precision angle control, and a handy adjust-and-lock swing bar, the Langdon Acme miter box represented the zenith of the Langdon Mitre Box Company's achievements. In 1906, two years after the introduction of the Langdon Acme, the George E. Rogers family sold the Langdon Mitre Box Company to the Millers Falls Company.

According to his nephew, John Owen, George Rogers "was not a production type." Decades after his death, older Millers Falls Company employees would recall their amazement at seeing him walking through the plant on a summer's day while dressed in a white suit that, upon his departure, was as clean as on his arrival.(12) Though Rogers' business interests were primarily local, they made him a wealthy man. By the standards of western Massachusetts, his Highland Avenue home was nothing short of a mansion, and at one time or another, he held financial interests in Rogers, Lunt & Bowlen, the Franklin County National Bank, the Greenfield Savings Bank, the Interstate Trust Company, the Greenfield Electric Light and Power Company, and the Greenfield Life Association. He served for decades on the Millers Falls Company's Board of Directors, first as Secretary, then as Treasurer and finally as Vice-President and General Manager. By the time he had reached middle age age, his involvement in the Langdon Mitre Box Company represented little more than a small, but lucrative, sideline.

George and Clara Rogers had two children: Philip, who would become the fifth president of the Millers Falls Company, and a daughter, Ethel, whose son John would become the sixth. George Rogers died on July 31, 1915, shortly after returning from a winter spent in Hawaii.

Illustration credits

- Housekeepers friend: Courtesy Roger K. Smith. (photocopy)

- Carpet stretcher: United States Letters Patent No. 138,560.

- Alexander gauge: The Langdon Mitre Box Company. Miller Falls, Mass. ... Millers Falls, Mass.: Langdon Mitre Box Co., 1881.

- Perfection gauge: Price list. Millers Falls, Mass.: Langdon Mitre Box Co., June 1904.

- Basic Langdon 1874: Millers Falls Co., Millers Falls, Mass. New York: Millers Falls Company, ca. 1874. p. 24.

- Basic Langdon 1880: The Langdon Mitre Box Company. Miller Falls, Mass. ... Millers Falls, Mass.: Langdon Mitre Box Co., 1881.

- New Langdon: The Langdon Mitre Box Company. Miller Falls, Mass. ... Millers Falls, Mass.: Langdon Mitre Box Co., 1881.

- New Langdon/panel saw: Ibid.

- Adjustable miter planer: M. L. J. Gunn bought of the Langdon Mitre Box Co. Millers Falls, Mass., February 29, 1884 (bill head).

- Rogers Miter Planer: Price list. Millers Falls, Mass.: Langdon Mitre Box Co., July, 1892.

- New Langdon Improved: Price list. Millers Falls, Mass.: Langdon Mitre Box Co., May 1887.

- Langdon Improved: Ibid.

- Langdon Improved back stop: Author's photo.

- Card sorter: United States Letters Patent No. 177,010.

- Auger handle No. 3: Catalogue no. 35. Millers Falls, Mass.: Millers Falls Co., 1915. p. 98.

- Auger handle No. 03: Ibid. p. 98.

- Star miter box: Price list. Millers Falls, Mass.: Langdon Mitre Box Co., April 1903.

- Langdon Acme: Price list. Millers Falls, Mass.: Langdon Mitre Box Co., June 1904.

- Rogers' home: George E. Rogers Residence, Greenfield, Mass. Greenfield Mass.: W. E. Wood, 1908. (postcard)

References

- “Millers Falls.” Gazette & Courier (Greenfield, MA), July 13, 1874; September 28, 1874, November 23, 1874, July 19, 1875; “Turners Falls.” Gazette & Courier (Greenfield, MA), June 7, 1875.

- “Greenfield Items.” Gazette & Courier (Greenfield, MA), April 5, 1875; July 26, 1875.

- Greene & Brandt stretcher: United States Letters Patent No. 138,560; ad for Langdon Housekeeper's Friend is courtesy Roger K. Smith.

- Price, Benjamin, and Steuart, Arthur. American Trade-mark Cases Decided by the Courts of the United States, both State and Federal and by the Commissioner of Patents, and Reported between 1879 and 1887. Baltimore: Cushings and Bailey, 1887. p. 621-628.

- Ibid. p. 625.

- Ibid. p. 627.

- United States Letters Patent No. 177,710.

- United States Letters Patent No. 484,050.

- Paul Jenkins. The Conservative Rebel: a Social History of Greenfield, Massachusetts. Greenfield, Mass.: Town of Greenfield, 1982.

- United States Letters Patent No. 694,323.

- United States Letters Patent No. 834,073.

- Telephone interview, John J. Owen. March 5, 2005.